Also published on 22 January 2024 on Hey SoCal

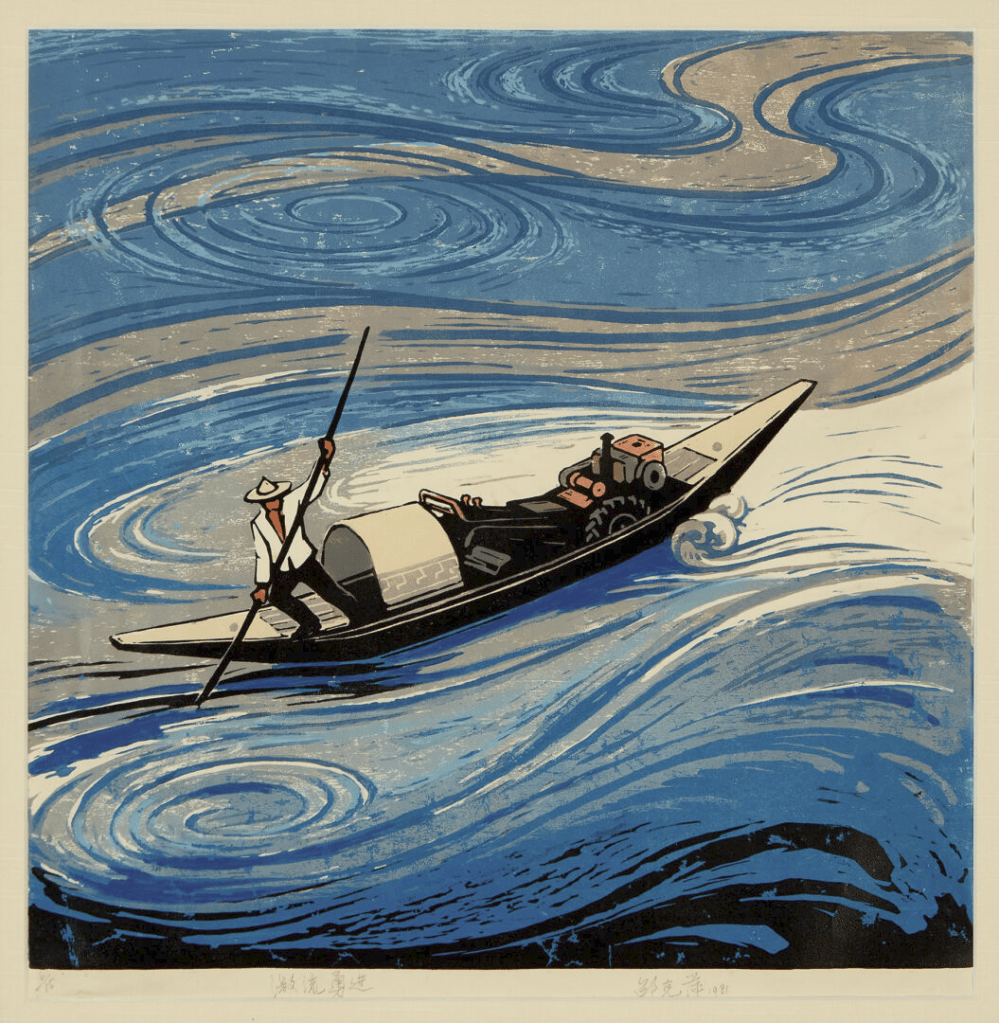

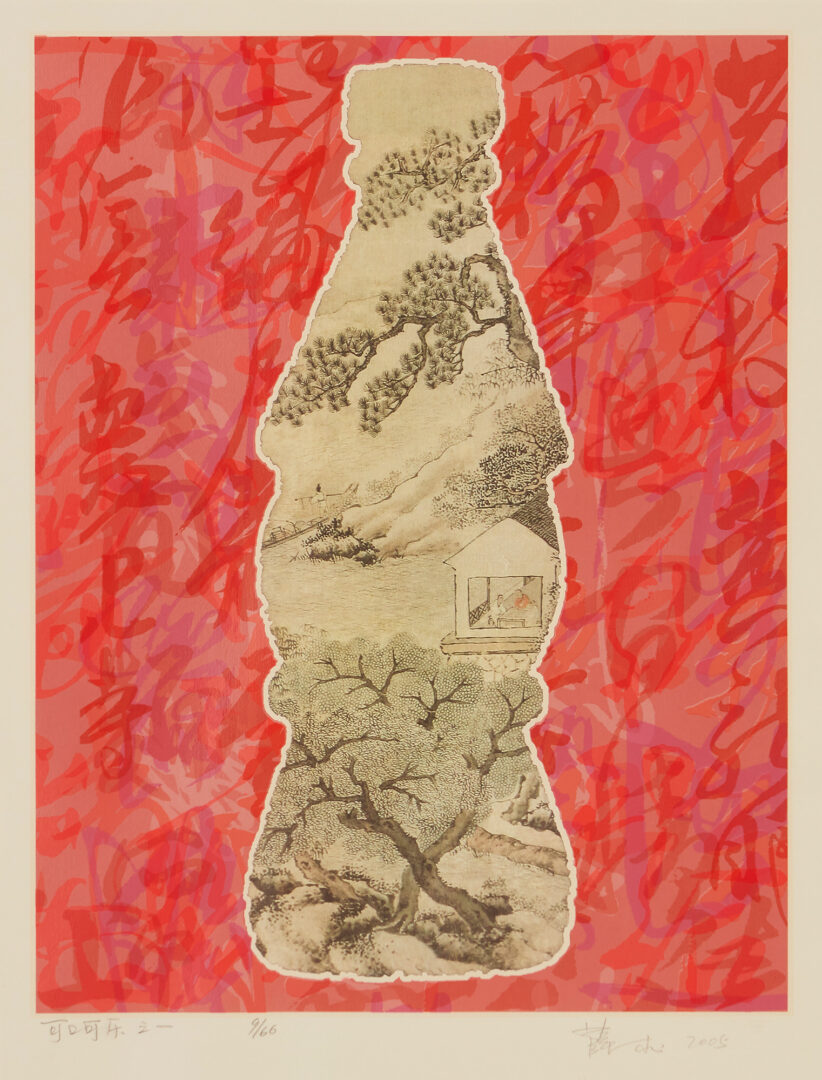

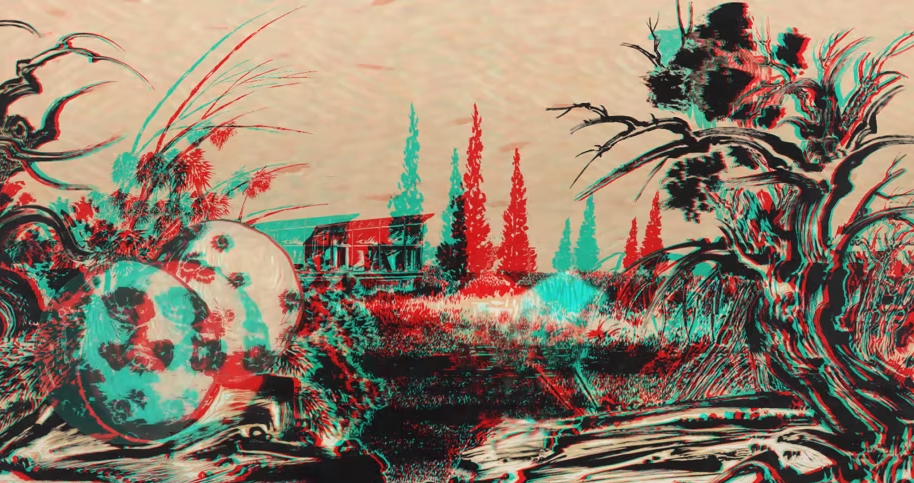

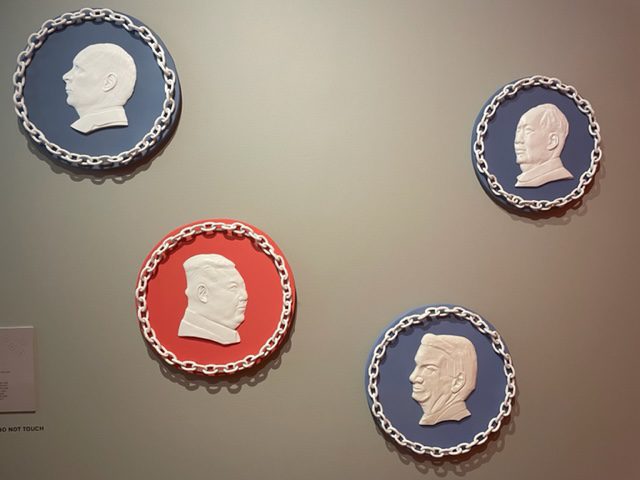

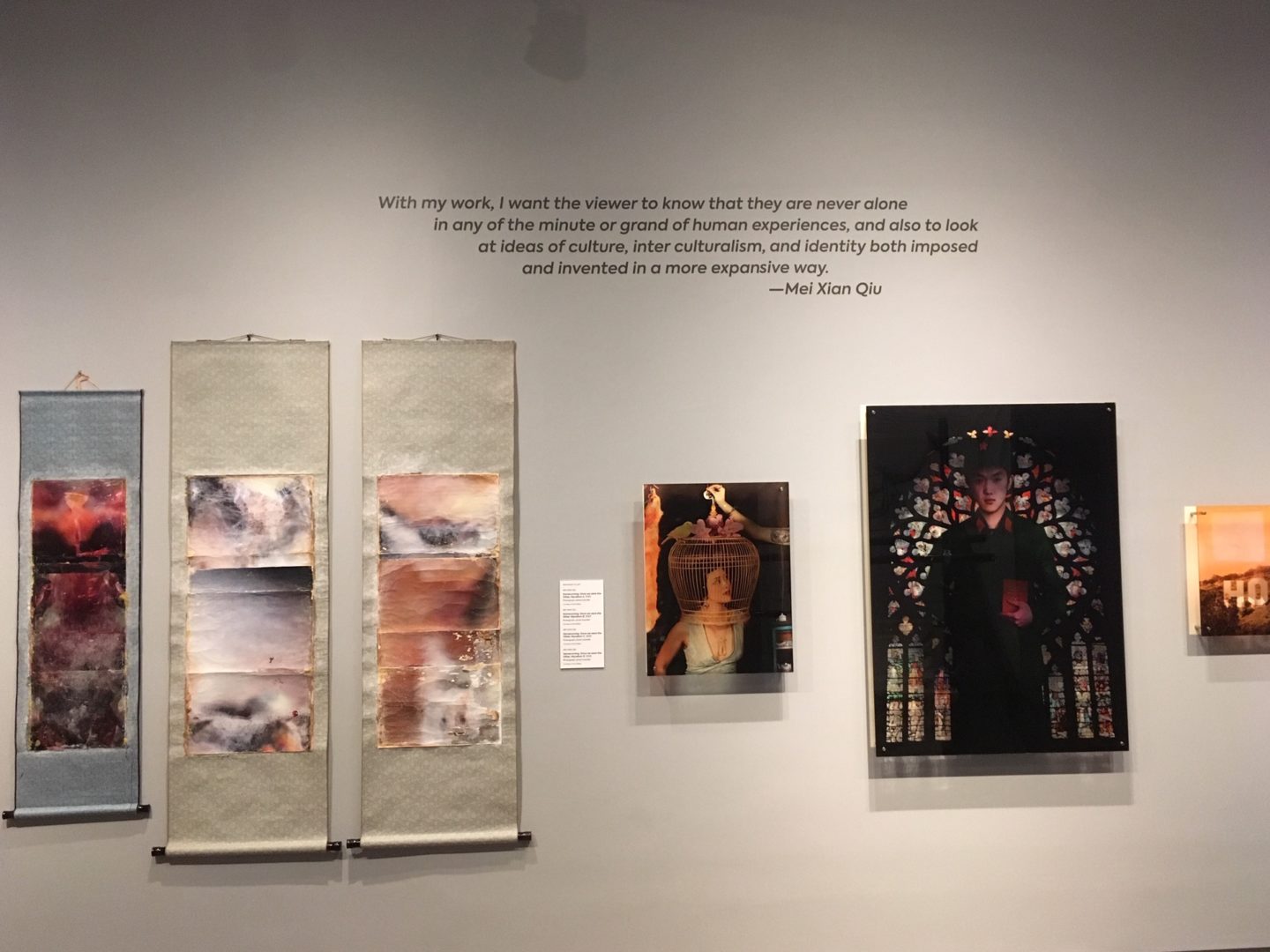

Clockwise from top left: Vivian Wenli Lin, The Joy Luck Mom Club, 2023; Jennifer Ling Datchuk, Love Yourself Longtime, 2019; Charlene Liu, China Palace, 2023; Rania Ho, Roundabout, 2023; Patty Chang, Invocations and Que Sera Sera, 2013, Andrew Thomas Huang, Kiss of the Rabbit God, 2019; Richard Fung, My Mother’s Place, 1990; Candice Lin, Lithium Sex Demons in the Factory, 2023; Ken Lum, Coming Soon, 2009 / Courtesy of USC Pacific Asia Museum

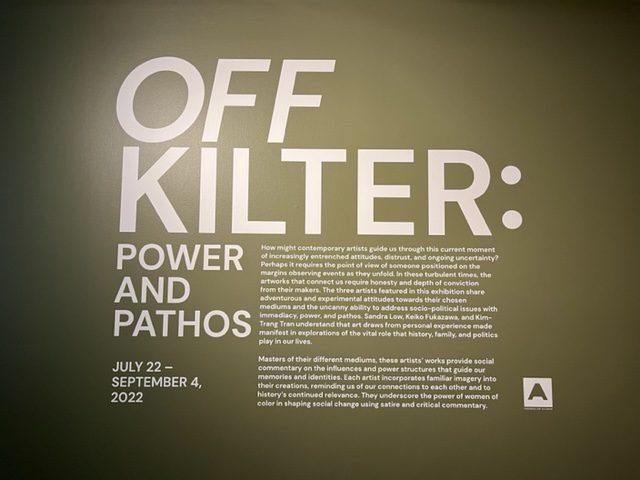

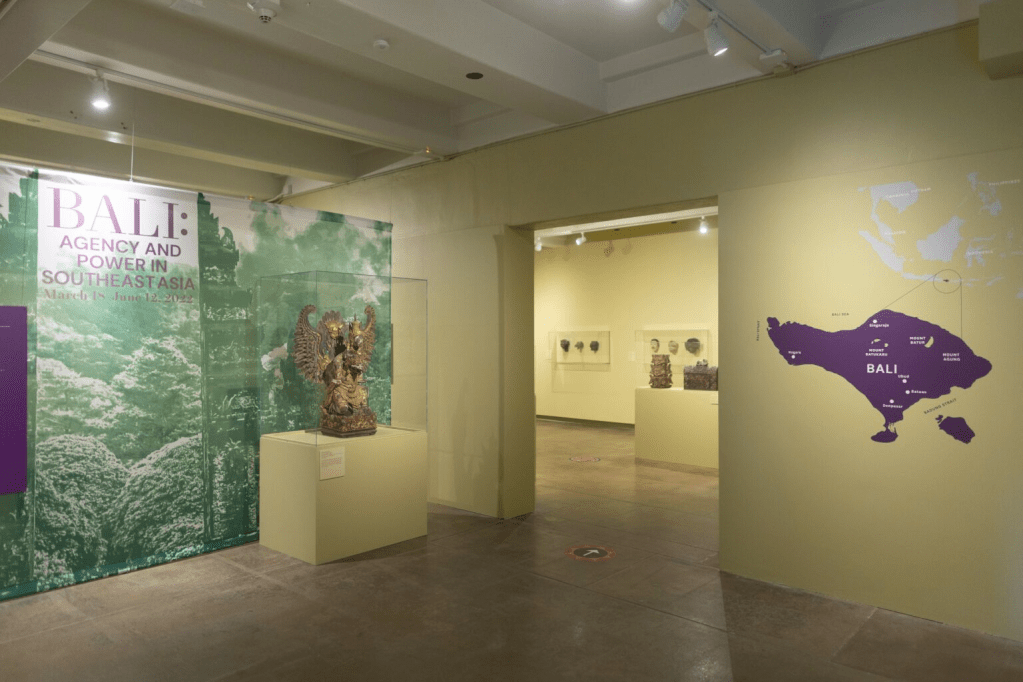

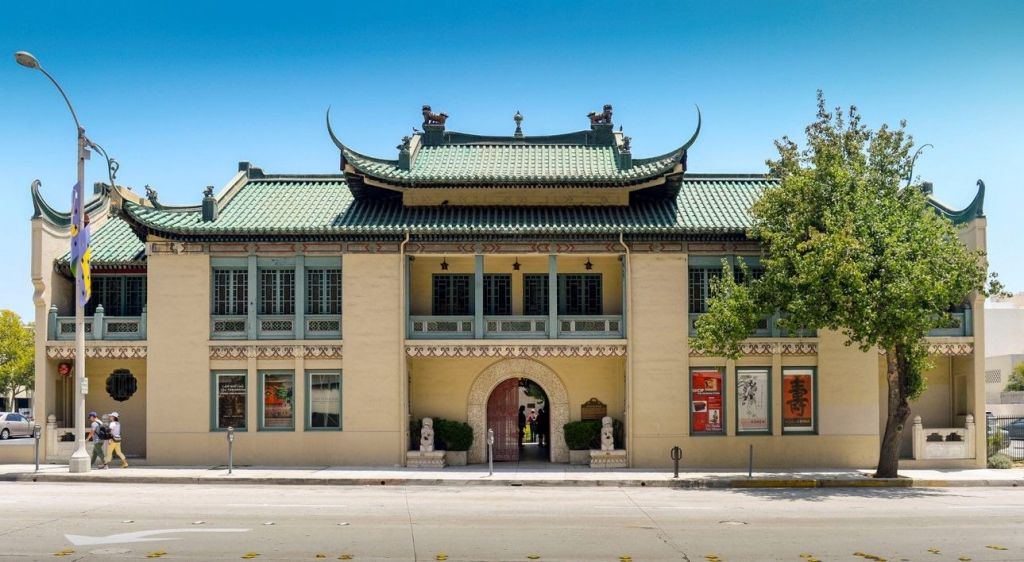

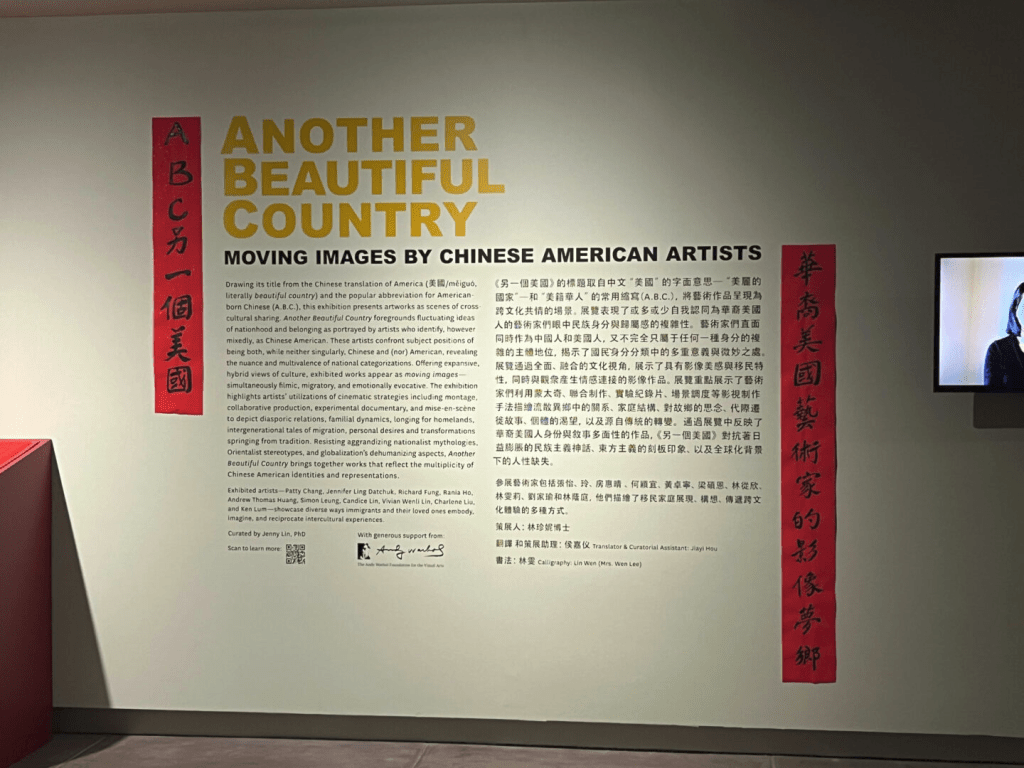

A touching experience awaits visitors to USC Pacific Asia Museum who come to see Another Beautiful Country: Moving Images By Chinese American Artists. On view from January 26 to April 21, 2024, the exhibition showcases ten artists whose work explores diverse ways immigrants and their families embody, imagine, and reciprocate intercultural experiences.

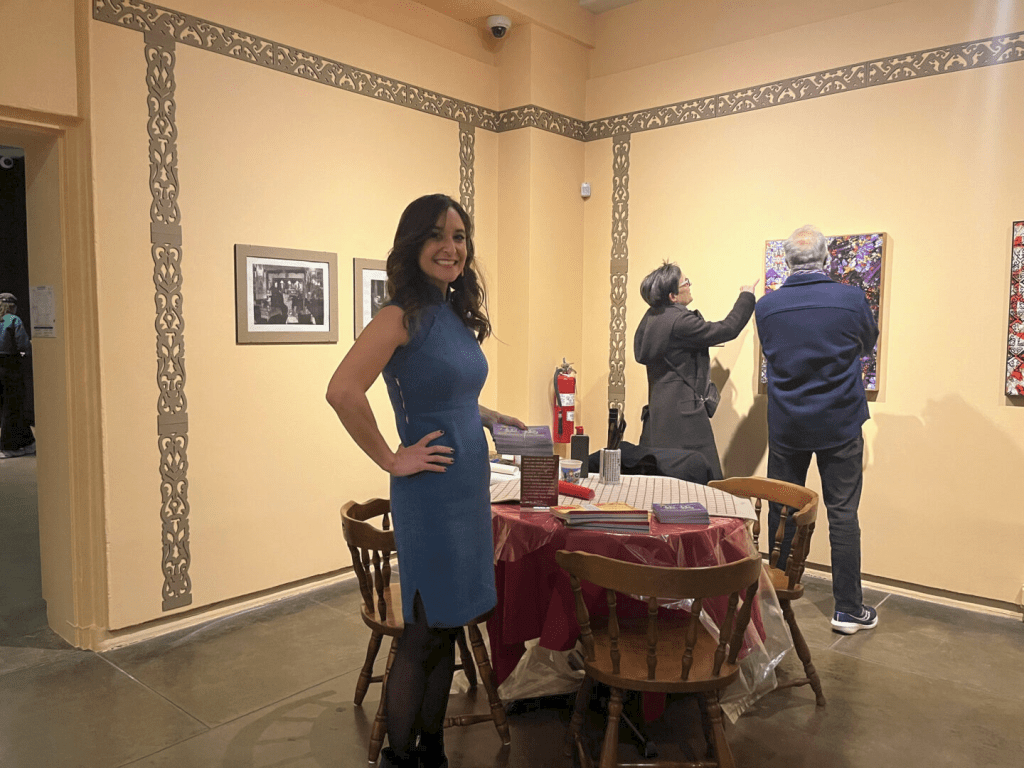

Curated by Jenny Lin, Ph.D., an Associate Professor of Critical Studies in Art and Design and Graduate Director of Curatorial Practices at the University of Southern California, the exhibition features the works of award-winning, distinguished, and renowned artists in their specialized fields: Patty Chang, Jennifer Ling Datchuk, Richard Fung, Rania Ho, Andrew Thomas Huang, Simon Leung, Candice Lin, Vivian Wenli Lin, Charlene Liu, and Ken Lum.

Drawing its title from the Chinese translation of America, 美國/měiguó, literally beautiful country, and the popular abbreviation for American-born Chinese (A.B.C.), this exhibition presents artworks as scenes of cross-cultural sharing. Another Beautiful Country foregrounds fluctuating ideas of nationhood and belonging as portrayed by artists who identify as Chinese American. These artists confront subject positions of being both, while neither singularly, Chinese and (nor) American, revealing the nuance and multivalence of national categorizations.

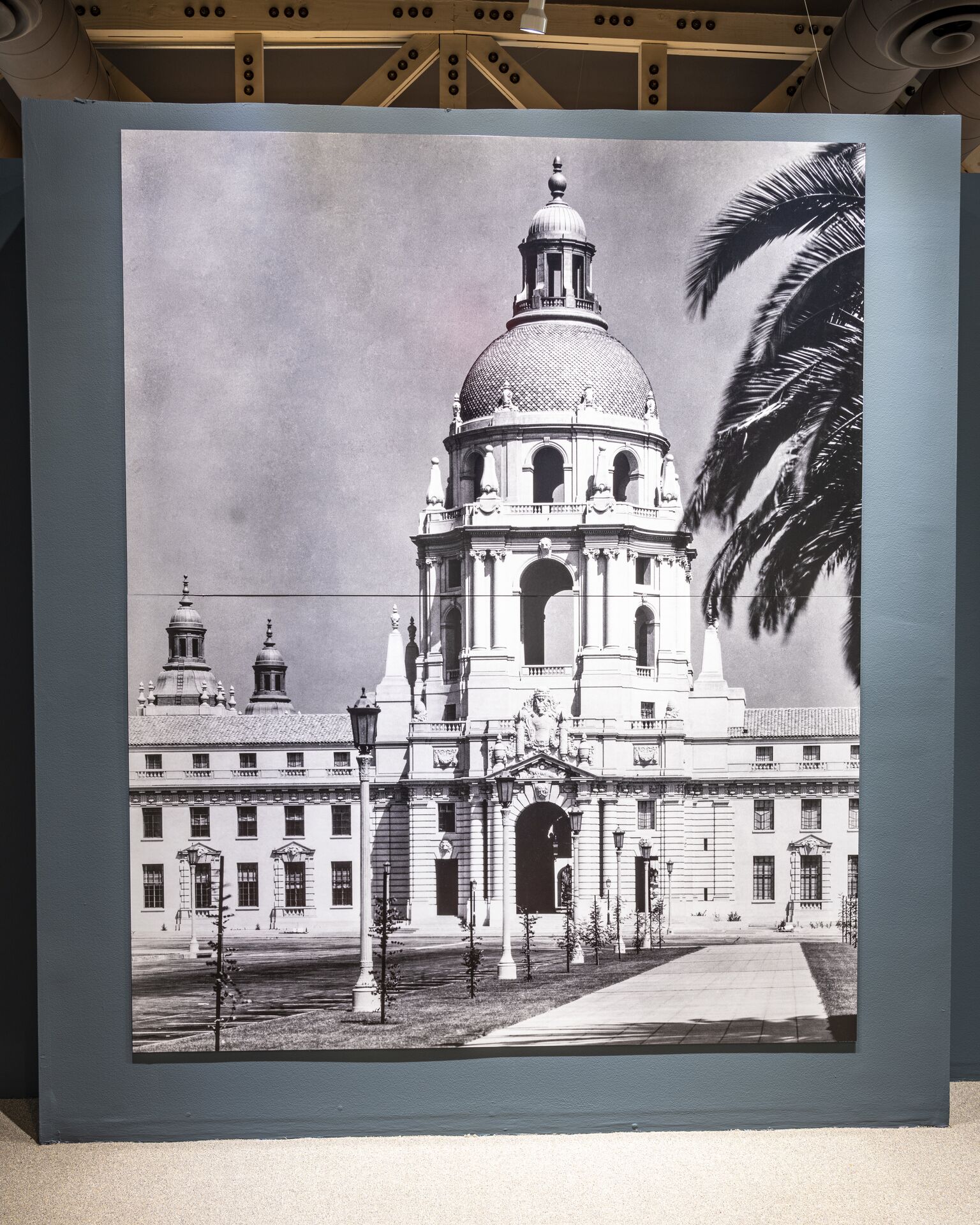

Another Beautiful Country installation | Photo by May S. Ruiz / Hey SoCal

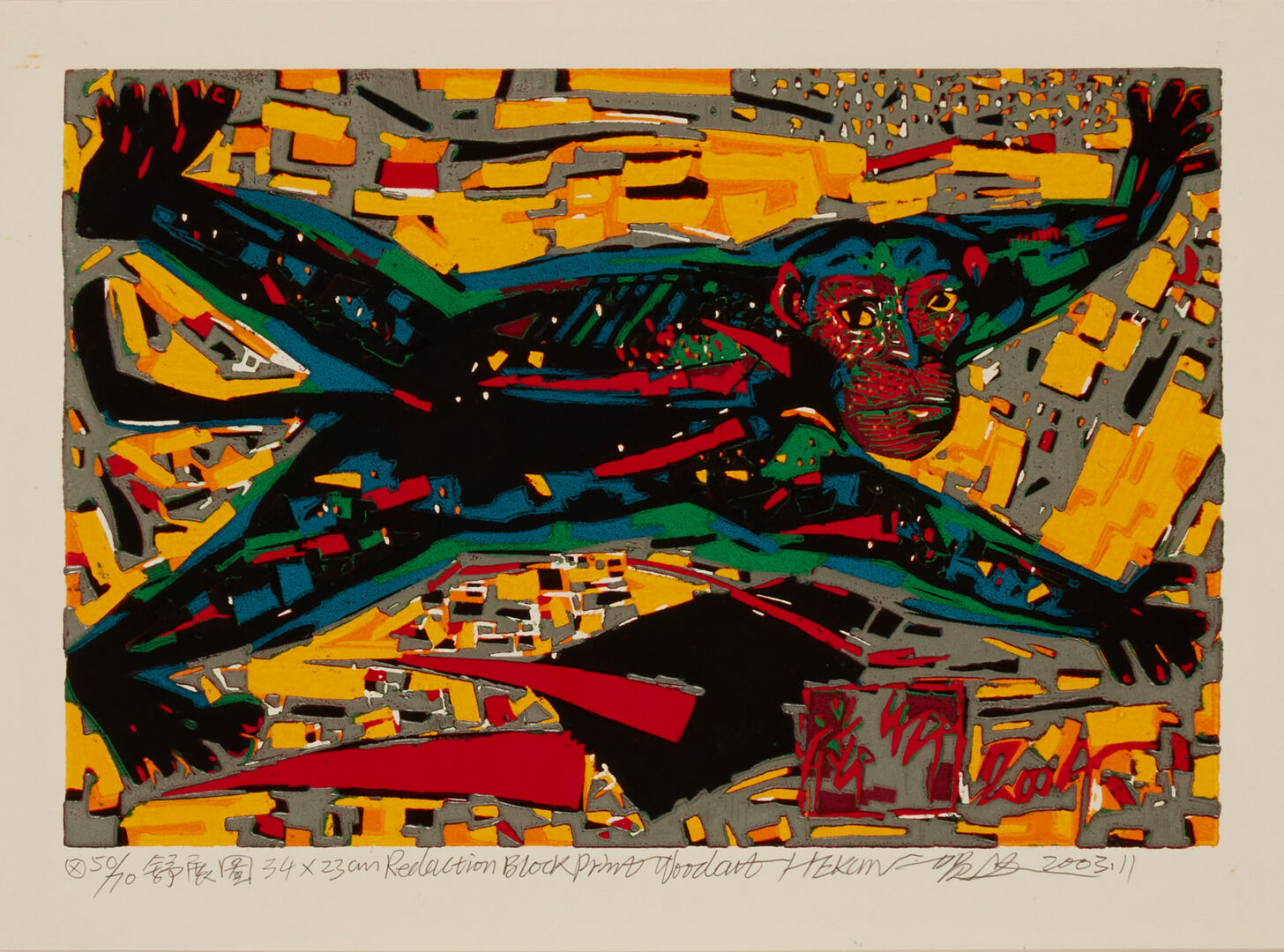

Another Beautiful Country is the first full exhibition that Lin curated at PAM but she’s certainly not a stranger to the museum. She explains via email. “I have had the pleasure of working with PAM on multiple programs. In 2020, I collaborated with USC students and colleagues to create an online exhibition, ‘In a Bronze Mirror: Eileen Chang’s Life and Literature,’ which showcases qipao/cheongsam from PAM’s collection. In October 2022, I organized the USC Visions & Voices event at PAM, ‘Taipei Night,’ which featured Taiwanese pop music, snacks and boba tea, as well as talks, a special print giveaway, and film screening and workshop by two of the exhibition’s included artists: University of Oregon Art and Printmaking Professor Charlene Liu and Occidental Media Arts and Culture Professor Vivian Wenli Lin.”

Putting on an exhibition typically takes time and Another Beautiful Country was several years in the making. Lin states, “I’ve been conceptualizing this project since I started my new position as Associate Professor of Critical Studies in USC’s Roski School of Art and Design in 2019. The preparation, including working with the wonderful PAM staff, fundraising (we received a major Exhibition Support Grant from The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Arts), crafting didactics, promotional materials, and a beautiful publication, organizing related programming, and my favorite part – talking with the artists – has been ongoing since 2021.”

Lin is also very familiar with the artists whose artworks are being showcased. She discloses, “I had been following, teaching, curating, and/or writing about the marvelous works of most of these included artists for years. I’ve had the good fortune of getting to know many of them as colleagues and collaborators, and our discussions and further research introduced me to more artists whose works align with the exhibition’s themes. All the selected artists inhabit and contemplate subject positions of being both, while neither purely Chinese and (nor) American. Each artist creates works that I see as moving images – considered both literally as videos, projections, and costume and set-oriented installations in transnational circulation, and figuratively as emotionally evocative and addressing migration and Chinese American diasporic relations.”

Jenny Lin during exhibition opening and reception | Photo by May S. Ruiz / Hey SoCal

Both curator and artist were active partners in choosing pieces that provoke discussion. Lin says, “Each artist is exhibiting one to three pieces/series but we made the selections together in extensive conversations. Featured artworks vary wildly in style, content, medium, and scale, with the exhibition encompassing a doormat, neon sign, prints, experimental videos, participatory documentary, large-scale projection, hybridized sculptures, and immersive installations. While vibrantly diverse, all these artworks closely relate to one another, and we’ve designed the exhibition to highlight those relations.”

Below is a sampling of artists’ works.

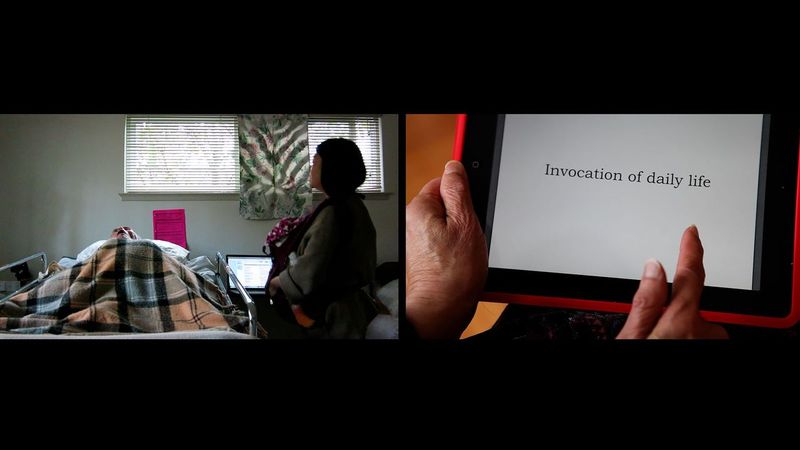

Patty Chang / 張怡

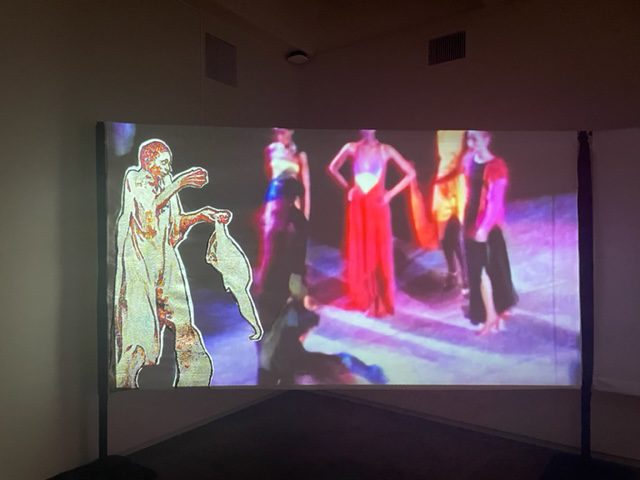

Invocations and Que Sera Sera, 2013

Two channel video installation, 3 Minutes, 45 seconds

Que Sera Sera features the artist singing her newborn baby to sleep. Chang gently rocks to and fro, her baby strapped to her body in a carrier – baby whimpers at first, and a tiny foot protruding from the carrier rests on the artist’s hip. Beside them lies Chang’s father in a bed with side rails; he is dying, breathing, but nearly motionless. She sings to him too: “Que Sera Sera, What Will Be Will Be.”

As in Chang’s video, wherein we encounter three generations of family members at distinct life stages, Que Sera Sera covers childhood, growing up and falling in love, and having a child of one’s own. Throughout the song, the narrator – the singer’s parent or singer-as-parent – tenderly responds to questions of what will be: “Will we have rainbows day after day? The Future’s Not Ours To See.” Both artwork and song urge us to be patient and present. With sorrow and joy, Chang inhabits a moment of intimacy with her baby and father, one drifting to sleep, the other drifting toward death.

Written by US composers Jay Livingston and Ray Evans, who often co-wrote songs for movies, “Que Sera Sera” became popularized by Doris Day, who belted the song as a secret signal to her kidnapped son, in Alfred Hitchcok’s 1955 film, The Man Who Knew Too Much. The song’s title, “Que Sera Sera,” which has since become a popular US phrase to express “what will be will is grammatically incorrect in the languages it assimilates (in Spanish it would be “lo que será, será,” in Italian “quel che sarà sarà”), a reminder of the imperfections of translation and language acquisition. Yet even if imperfectly, we learn new languages – studying in schools, speaking the words of a place we have migrated to, learning the native tongues of our parents, or grandparents; Chang’s son now speaks with her mother, his grandmother, in pǔtōng huà.

In Invocations, we catch a glimpse of Chang’s baby being rolled up, in stroller, to his grandmother. She embraces her grandson, she in paisley trousers, he in striped onesie and green leggings. Baby cries; grandmother exclaims, “Jīntiān nǐ zěnme chǎo!” (Today you are so noisy!). In the rest of Invocations, we see Chang’s mother’s hands, holding and swiping through a list of invocations that appear on a tablet. Her voice, soothing and steady, reads in accented English: “Invocation of loss of balance / Invocation of falling / Invocation of motor control / Invocation of envy / Invocation of incontinence / Invocation of caregiving / Invocation of catheter / Invocation of daily life / Invocation of isolation / Invocation of shame / Invocation of guilt / Invocation of longing…” The list of invocations related to growing older, disease, medical treatments, desire, everyday life, and ideas, at once quotidian and dreamy, reads like a poem.

List of Invocations, 2017 Letterpress print

Echoed in a print, List of Invocations hangs nearby the video installation. Light grey text in a clinical font appears on white paper; the lightness of the words, as well as their structural repetition, mimics life’s fleeting nature. Chang’s invocations are practical, magical, ethical, and perhaps, ultimately futile, albeit still worthwhile, as all states, emotions, and things shall pass; “what will be will be.” Chang’s Invocations and Que Sera Sera stand as offerings of familial intimacies and vulnerabilities, tenderly reminding us of life’s cruel and beautiful cycles.

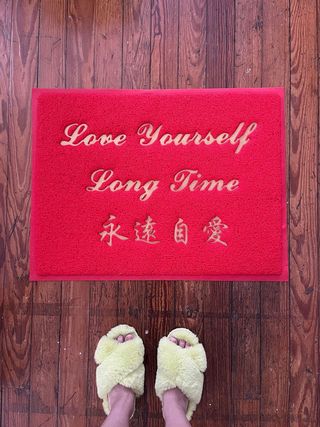

Jennifer Ling Datchuk / 玲

Love Yourself Long Time, 2019

Doormat

and

Love Yourself Long Time, 2021

Mirrored acrylic and neon

Love Yourself Long Time (2019) takes form in two artworks: a glowing custom-made neon, mirrored sign and a red doormat, nearly identical to those meant to be stepped on, elevated in the exhibition via the museological standard of placing art objects upon pedestals. The phrase, Love Yourself Long Time, illuminated in neon on the sign (with yourself lighting up letter by letter) and embossed in golden English letters and Chinese characters on the doormat, references a scene in director Stanley Kubrick’s 1987 film Full Metal Jacket, in which two US soldiers stationed in Vietnam negotiate with a Vietnamese sex worker, who advertises: “Me love you long time.” Datchuk twists the line, which has circulated widely throughout American popular culture. Asserting agency, she turns the grammatically incorrect offer of the subjugated, exoticized sex worker into a positive affirmation encouraging self-love.

Two Week Wait, 2021

Porcelain, gold mirrored glass tiles, mirrored acrylic, candles

Two Week Wait (2021) is a sculpture reflecting on female health and safety, as well as the common Covid-19 quarantine period. Constructed like a shimmering alter with Chinoiserie, famille rose porcelain candlesticks stacked upon its steps, Two Week Wait acknowledges ways in which people in North America and Western Europe often look to Eastern symbols and rituals for spiritual fulfilment. Simultaneously, the artwork sparks varied emotions that may accompany pregnancy, shared across the globe: exuberance, joy, fear, terror, sorrow, trepidation, regret, excitement, anticipation.

The title, Two Week Wait, refers to the typical time of waiting between ovulation and menstruation, in other words the time it takes to confirm pregnancy. Women internationally, including in the United States and People’s Republic of China, have long struggled and continue struggling for bodily autonomy and reproductive rights.

(Jennifer Ling Datchuk will be giving an artist talk in the galleries with Ken Lum at PAM on Saturday, January 27 at 1pm)

Rania Ho / 何颖宜

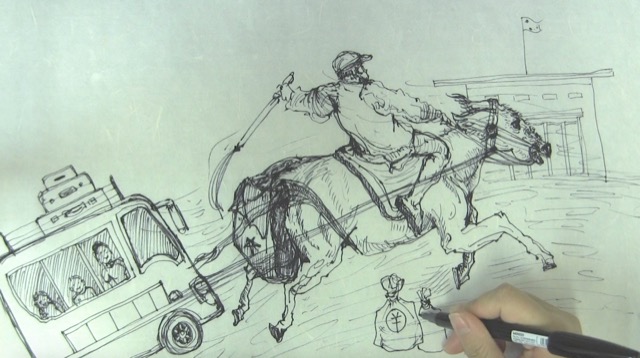

Roundabout, 2023

Single channel video, 14 Minutes, 29 seconds

Roundabout features US-born, China and US-based artist Rania Ho walking in circles in a demolition site in her video projection. A fade-in technique makes the artist appear and disappear as she walks in large concentric circles, her body attached to string, stanchion, and ball bearing, creating a fulcrum point. As Ho steadily walks each circumference, she sprays the ground from a hose attached to a fluorescent green water pack she wears on her back. The spray emits a hum and leaves a ghostly residue that slowly begins evaporating over the course of the video. The gesture, along with Ho’s uniform-like black clothing and industrial hose, recalls decontamination processes used in China following the initial outbreak of Covid-19.

Those who live or have spent time in China may also be reminded of the poetic practice of people, usually elderly, writing calligraphy in water on the stone pathways of parks. For others, Ho’s overlapping circles resemble the logo of the Olympics, held in summer 2008 and winter 2022 in Beijing, where Ho made the video. As the artist describes in her writing about the piece, the demolition site, Luoge Zhuang Village of Shunyi District, used to be filled with artists’ studios (she herself had a studio on the outskirts of the village), which were hastily demolished in 2021, supposedly to make way for Olympics-related construction that never came to be.

The fixed camera surveys the demolition site, with its cracked surface and rubble, below a smoggy sky and deciduous trees, sans leaves. Ho’s body, dwarfed by the site and her circumambulation – at once like a Buddhist ritual and Sisyphean task – persist on infinite loop, a quiet mourning for the fallen studios on the outskirts of Beijing.

You Kinda Had to Be There (Motel Cali), 2005/2023

Single channel video, 6 minutes, 30 seconds, edited from 24 hours

Visitors encounter a very different, comical, high-spirited representation of Beijing’s art scene in the mid-aughts in Ho’s You Kinda Had To Be There (2023). This project, tucked behind a curtain, consists of a karaoke-inspired video installation with a shimmering tinsel backdrop, headphones, and microphones for museum goers who fancy singing along. The video features artists singing or performing in various ways The Eagle’s “Hotel California,” a common karaoke song that most all of us love to hate. Ho created this 6 minute, 30 second video (the duration of the actual song) by editing footage of a 24-hour participatory event she organized in 2005. For the original event, part of Complete Art Experience Project (CAEP/联合现场地计划), a city-wide art initiative in Beijing, Ho invited artists and other community members to sing “Hotel California.”

The creative, offkey renditions by many of Beijing’s most active artists of the day collectively compose a kind of time capsule of a free reeling art world, set amidst the frenetic pace of intense urban development. Ho’s moving images of artist friends, goofing off and singing “Hotel California,” especially when juxtaposed against the solitude of her post-Covid-19 Roundabout, wherein the only other creature to appear is a dog we later hear barking, stresses the vitality of friendship, chosen family, and playful communal gatherings.

(Rania Ho will be giving an artist talk with Simon Leung at PAM on Wednesday, April 3 at 6pm)

Andrew Thomas Huang /黃卓寧

Kiss of the Rabbit God, 2019

Single channel video, 14 minutes, 29 seconds

and

Rabbit God Statue, 2019

Mixed media with adornments by Tanya Melendez

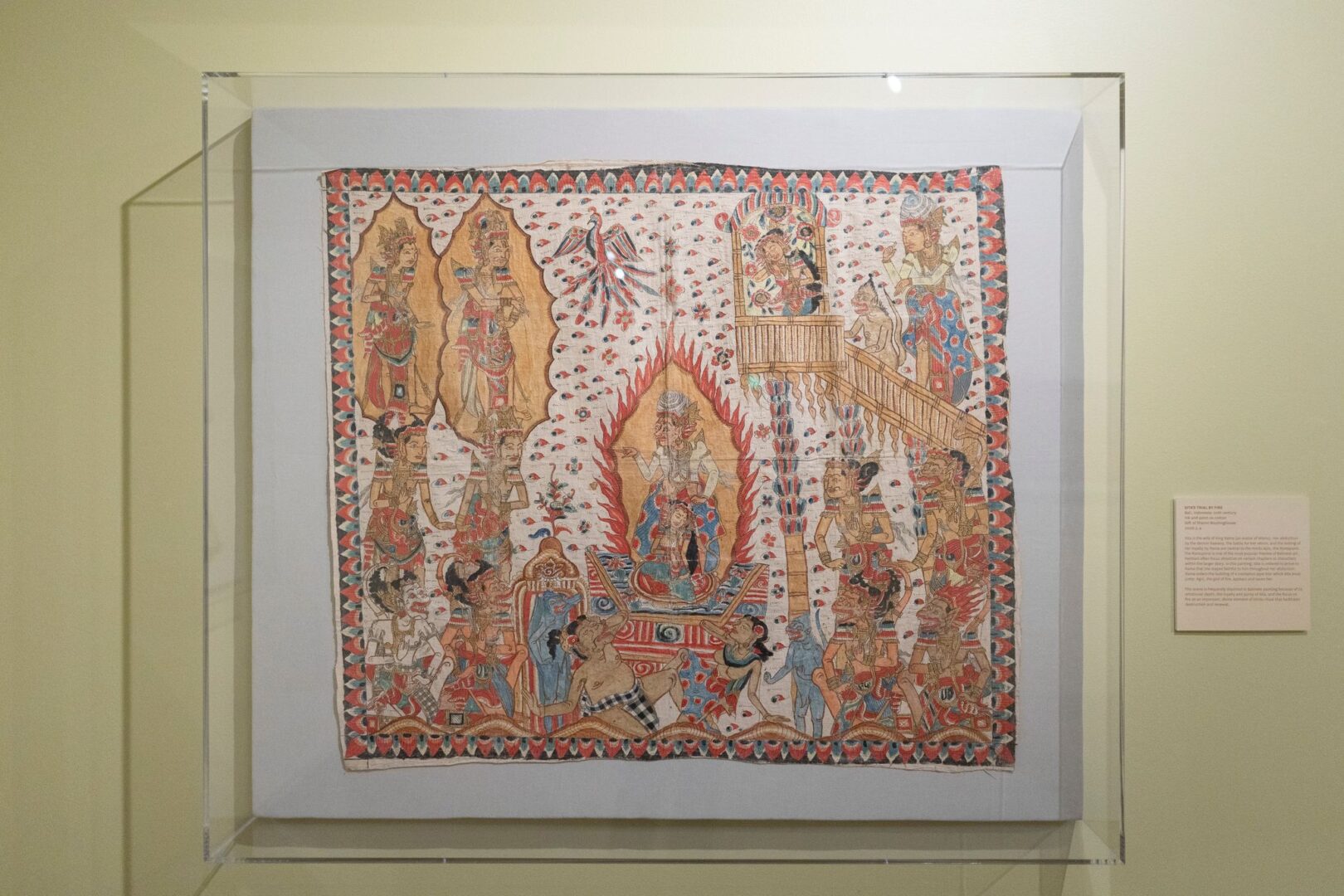

Kiss of the Rabbit God is a fairy tale of queer love. The protagonist, a young Chinese American man named Matt, played by actor Teddy Lee, feels trapped working in his parents’ Chinese restaurant (filmed on location in LA’s Chinatown), until he meets the deity, Tu’er Shen (Rabbit God), in human form, played by actor Jeff Chen.

The two young men embark on a loving, celestial sequence that allows Matt to embrace his gay identity through self-discovery and by entering into a mystical Chinese legend. Accompanying Huang’s short film stands Huang’s Rabbit God Statue, which the artist recently showed in another exhibition of Kiss of the Rabbit God in Hong Kong. Kiss of the Rabbit God’s setting nods to Huang’s own family’s 40-year history running a Cantonese restaurant in southern California.

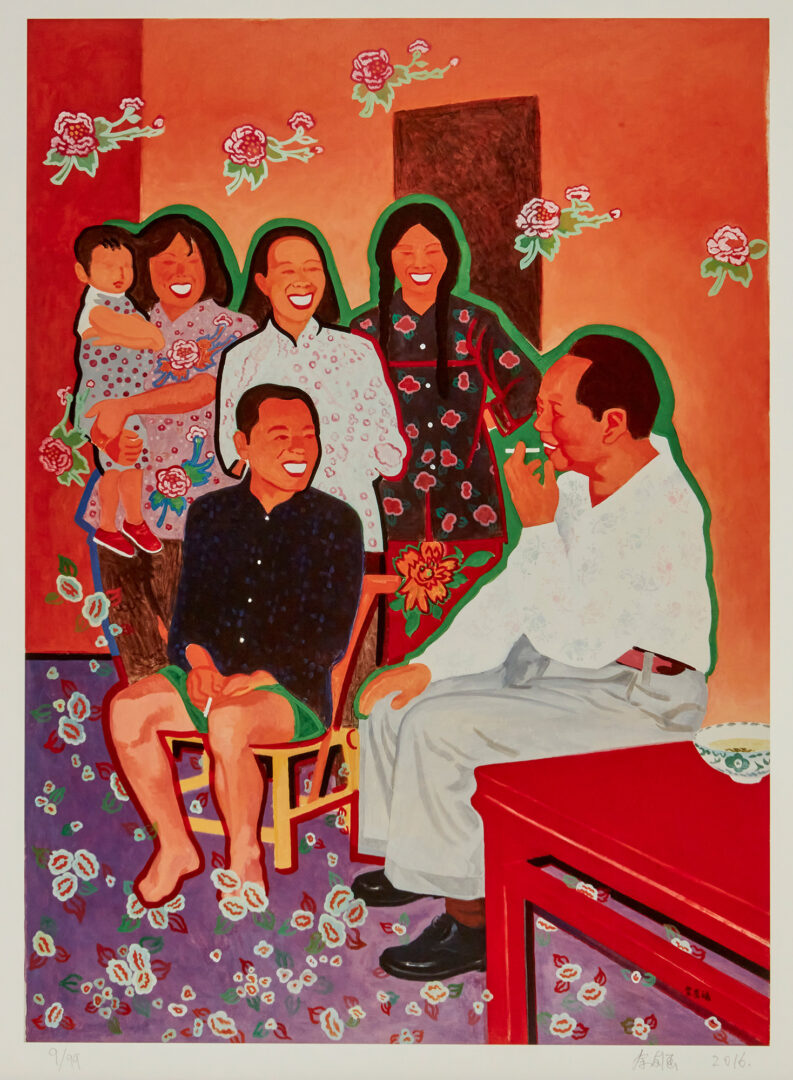

Vivian Wenli Lin / 林雯莉

The Joy Luck Mom Club: Untold Narratives of Migration, 2023

Single channel video, 10 minutes

Vivian Wenli Lin’s “The Joy Luck Club: Untold Narratives of Migration | Photo by May S. Ruiz / Hey SoCal

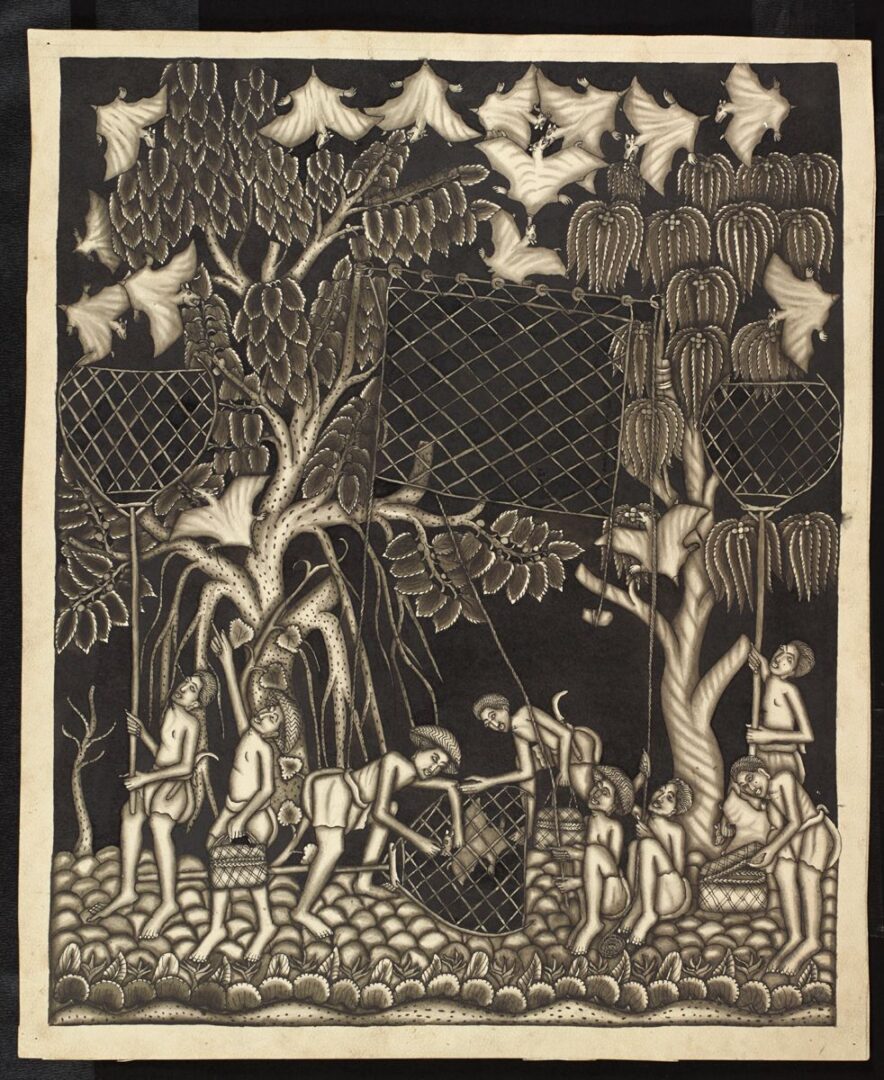

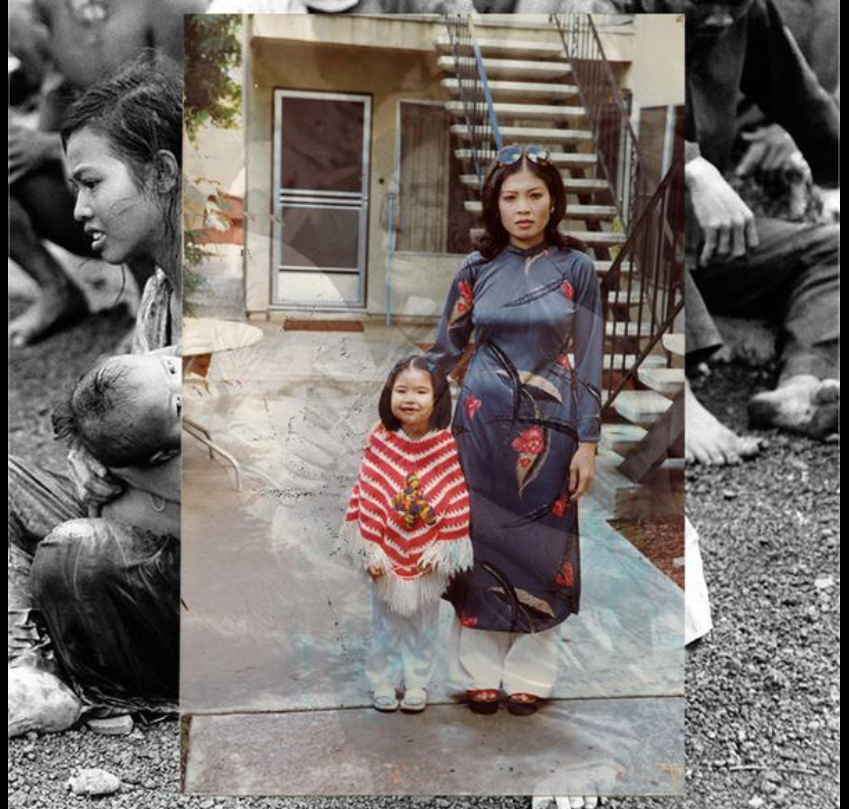

The Joy Luck Mom Club: Untold Narratives of Migration is a mixed-methods participatory, interview and observation-based video project. In turning to lost and untold narratives of migration that have been kept silent or hidden away, Lin centers the diasporic identities that were excluded in mainstream representations of the immigrant narrative.

Inspired by the film The Joy Luck Club (1994) based on the novel by Amy Tan and directed by Wayne Wang – a film considered to be a dominant representation of the Asian American immigration narrative, the project attempts to contribute to the untold/unheard/silenced and forgotten narratives of women’s migration. Immigrant stories are often centered on generational trauma as a result of the self-sacrificing Asian mother.

The narratives shared via The Joy Luck Mom Club: Untold Narratives of Migration attempt to decenter the “Asian American” immigration story, through the use of participatory media making methods, to gather transnational stories between Asia/America, blurring the lines between how these histories of migration can be remembered as fact or fiction, memory or truth. Lin offers an opportunity for museum visitors to share their own “joy luck mom club” moments; a flier with QR code and instructions is available near the video.

(Vivian Wenli Lin will be holding a related workshop, “The Joy Luck Mom Club – Participatory Video,” on Saturday, March 23 from 11:30am-2pm)

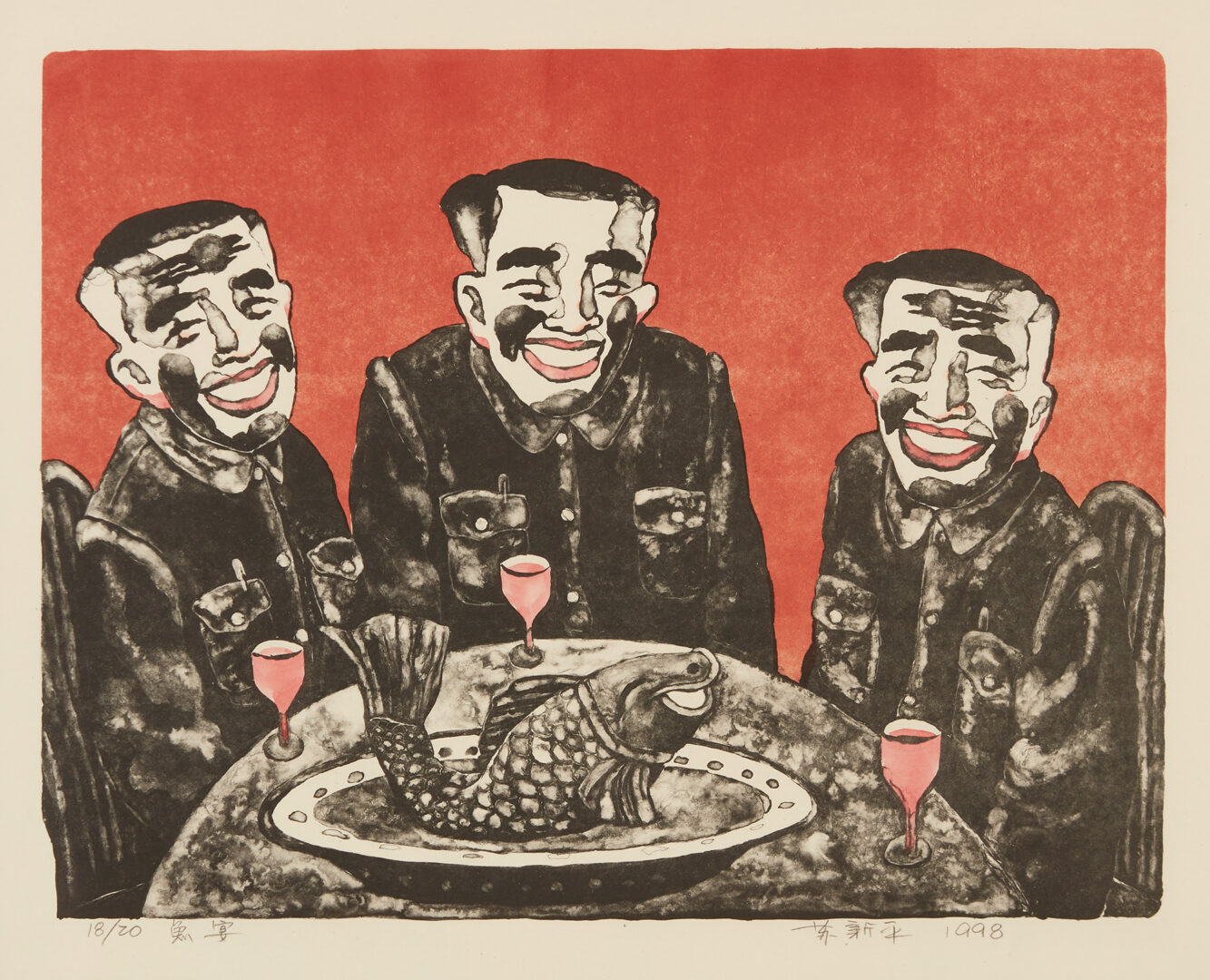

Ken Lum /林蔭庭

Coming Soon, 2009/2023

C-print reproduced on vinyl

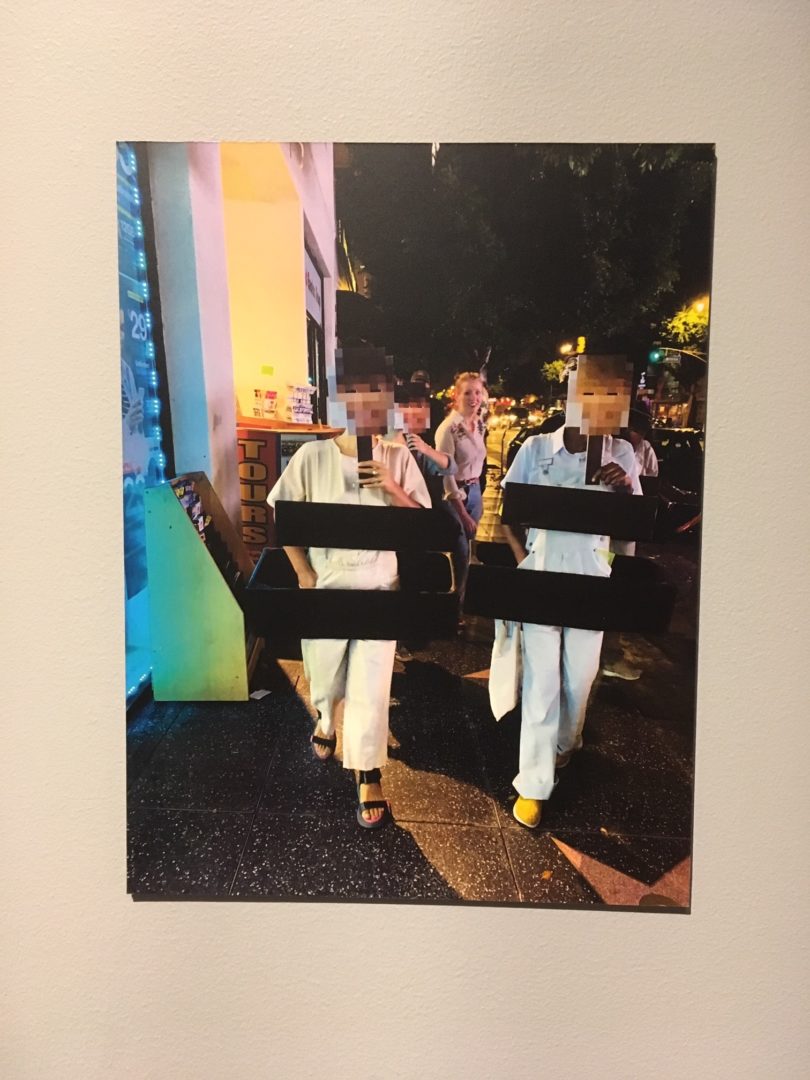

The print, facing outward from a museum window, resembles a family photograph of a mixed-race European-Asian couple and their biracial daughter. This picture of a seemingly benign nuclear family, paired with the text Coming Soon in both English and Chinese characters, resembles an advertisement for a Hollywood movie or global fashion brand, though without slick styling or airbrushed perfection. The image counters historical anti-miscegenation laws and parodies superficial corporate diversity campaigns. Simultaneously, for those in the know,

Coming Soon reminds us of the ability of images to deceive and the importance of questioning our assumptions; Lum divulged to me that the people in the photograph are not in fact a family, but three strangers the artist met in Beijing.

(Ken Lum will be giving an artist talk in the galleries with Jennifer Ling Datchuk at PAM on Saturday, January 27 at 1pm)

Lin has consciously and mindfully put together an extraordinary show. Another Beautiful Country is an impressive collection of thought-provoking artwork that invites a response and reaction from its audience.

She expresses magnificently what she wishes the exhibition engenders. “I hope people will spend time with each artwork, absorbing the multivalent presentations of Chinese American experiences and identities, which collectively unravel grand historical narratives, nationalist myths, and essentializing stereotypes. I hope people visiting the exhibition will come away with admiration for these artists’ fantastic works and the unique, nuanced ways they portray Chinese American relations. Ultimately, I hope the exhibition will inspire visitors to reflect on their own familial stories of migration and imagine belonging in another beautiful country, a place where generous, cross-cultural relations flourish.”