Also published on 23 September 2024 on Hey SoCal

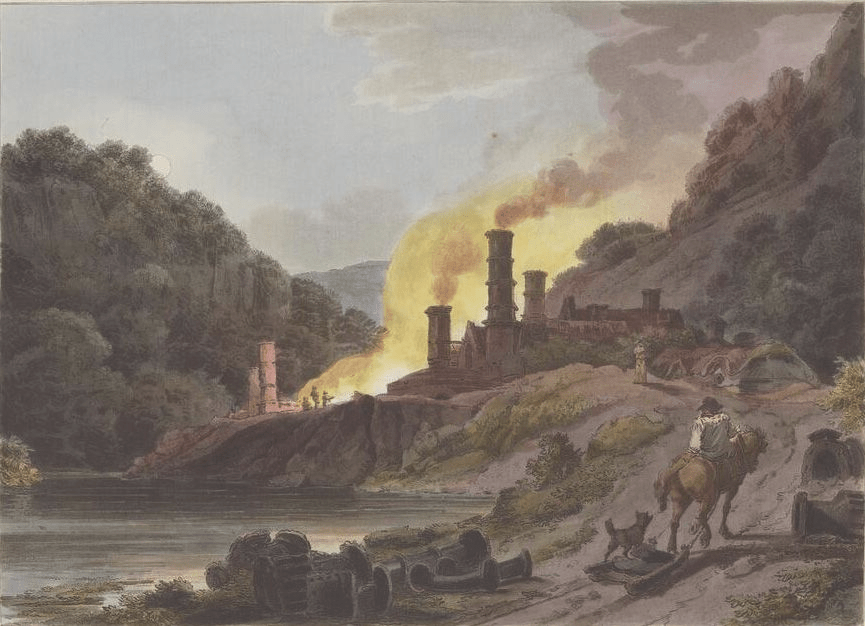

Philippe Jacques de Loutherbourg, Iron Works of Coalbrook Dale in The Romantic and Picturesque Scenery of England and Wales | Photo courtesy of The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens

Almost daily over the past two decades, we’ve been hearing about climate change – when we experience a heat wave, when we witness a wildfire, when we see on the news an arctic blast on the East Coast, or when we learn about melting icebergs in the Antarctic Ocean.

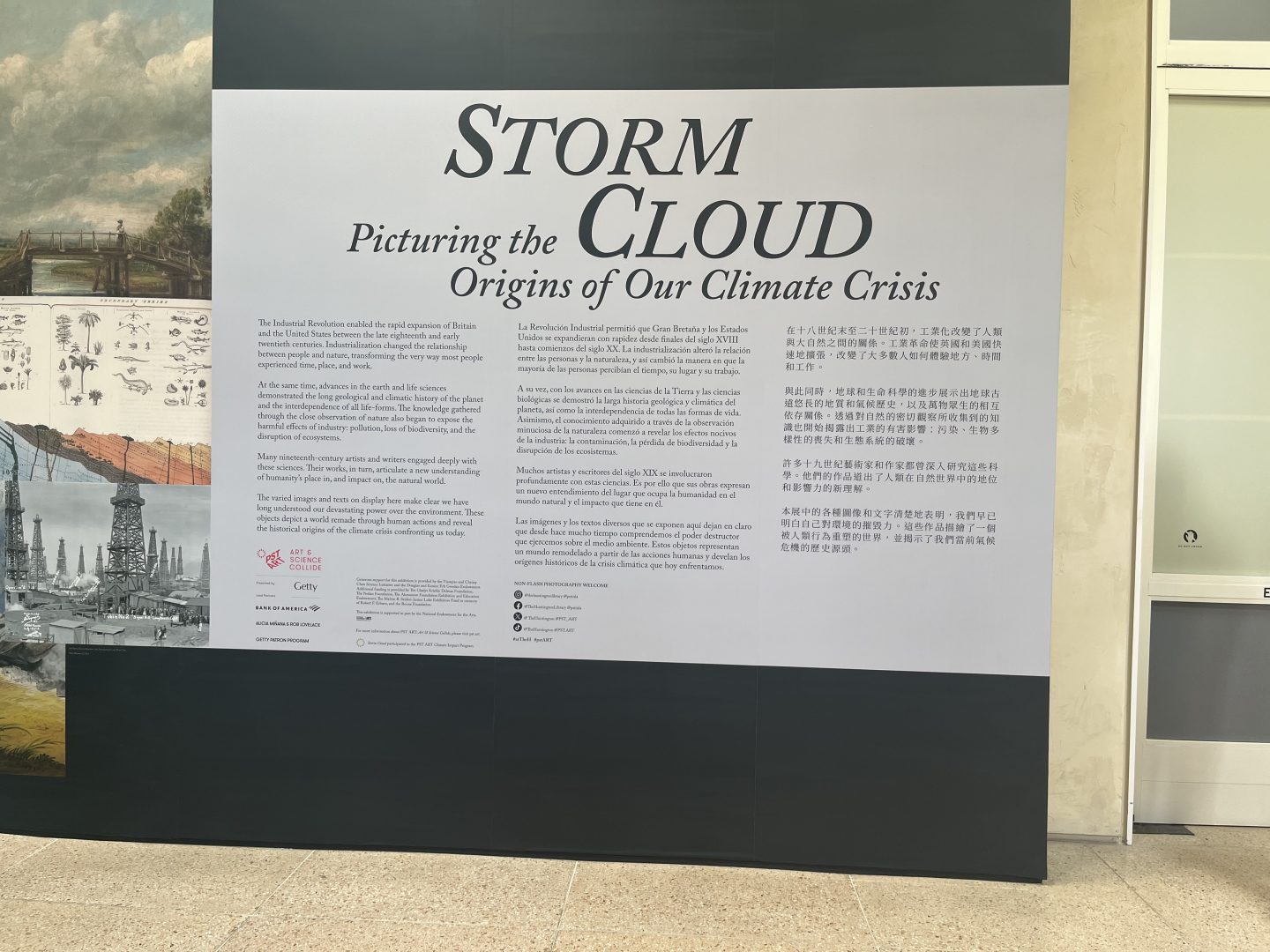

Yet this phenomenon didn’t just happen in the last 20 years, or even during our lifetime, as the “Storm Cloud: Picturing the Origins of our Climate Crisis” exhibition at The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens demonstrates. On view from September 15, 2024 through January 6, 2025 at the Marylou and George Boone Gallery, it will be on display concurrently with “Growing and Knowing in the Gardens of China.”

The two shows are part of PST ART: Art & Science Collide, a regional event presented by Getty featuring more than 70 exhibitions and programs that explore the intersections of art and science, past and present.

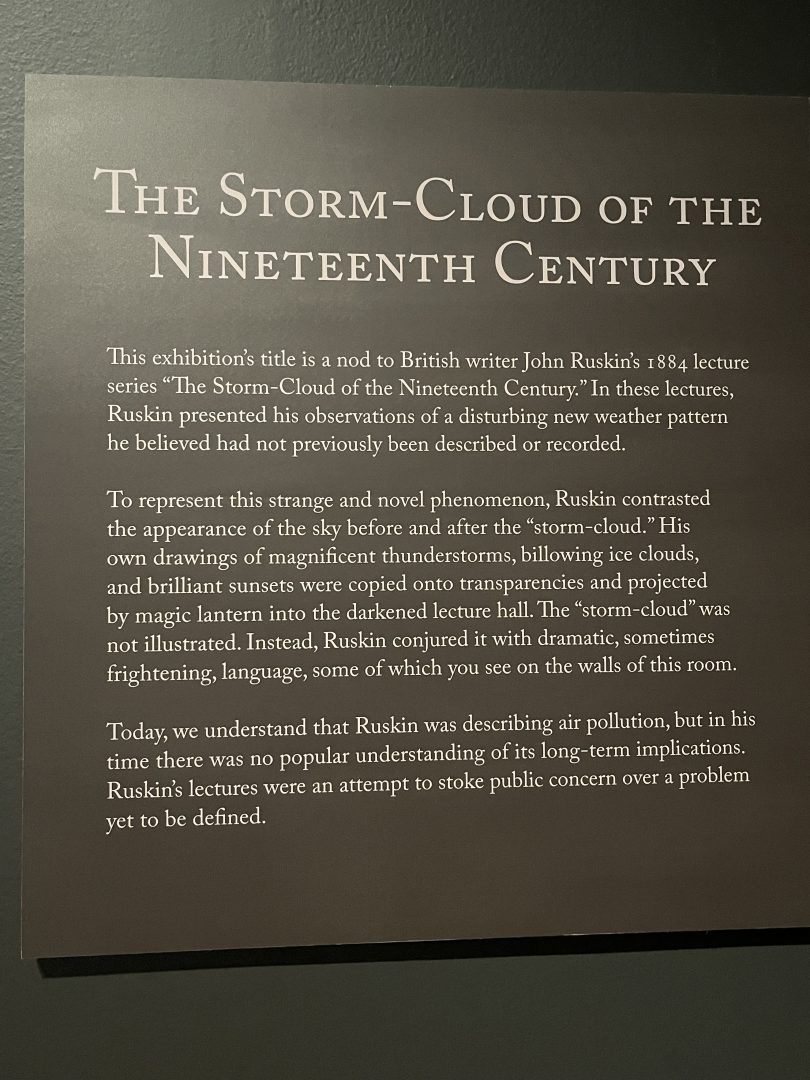

Its title originates from a series of lectures given by British writer and art critic John Ruskin in 1884. In “The Storm Cloud of the Nineteenth Century,” he conveyed concern over the changing appearance of the English sky caused by the smoke generated by coal-fired factories.

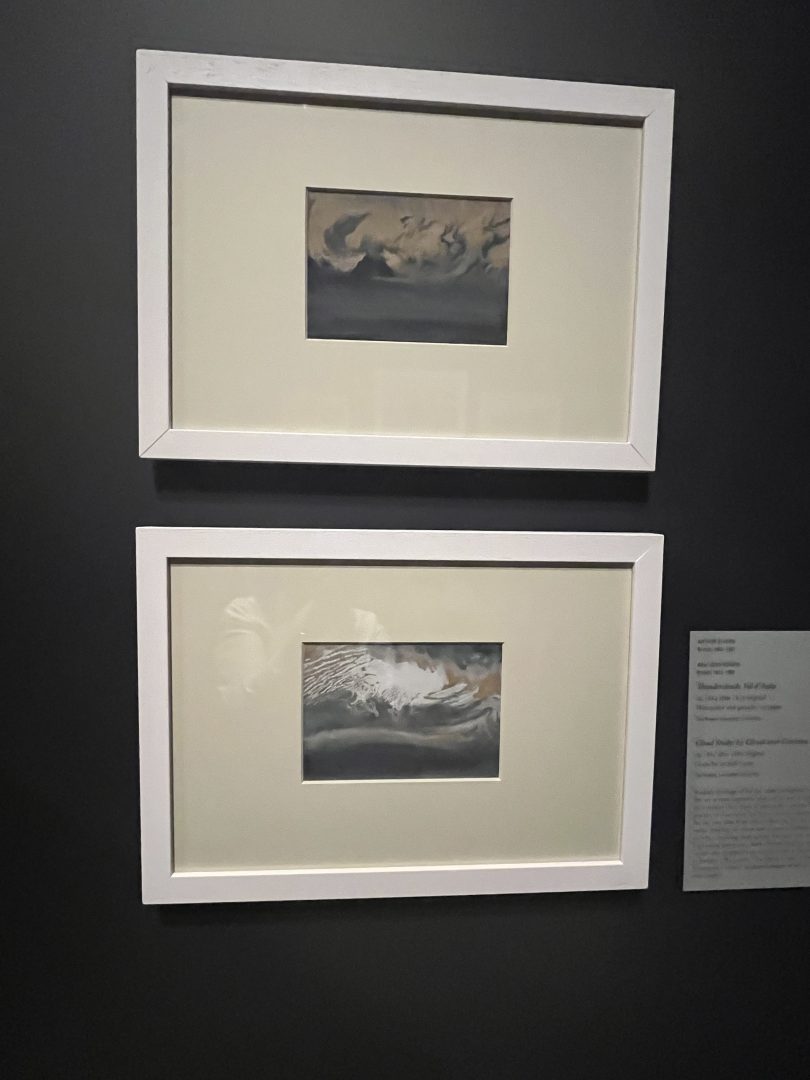

A pair of drawings that illustrates his “Storm Cloud” lecture – Thunderclouds, Val d’Aosta (1858) and Cloud Study: Ice Clouds over Coniston (1880) – is on loan to the exhibition from the Ruskin Museum and Research Centre at Lancaster University (U.K.). Ruskin made drawings of the sky throughout his life. These records of his observations helped him understand how the appearance of the sky had changed due to industrial pollution.

To give visitors to the show greater insight, a companion book has been published and contains two major essays and 16 contributions by academics, art curators, authors, educators, environmental activists, graphic designers, poets, and scientists.

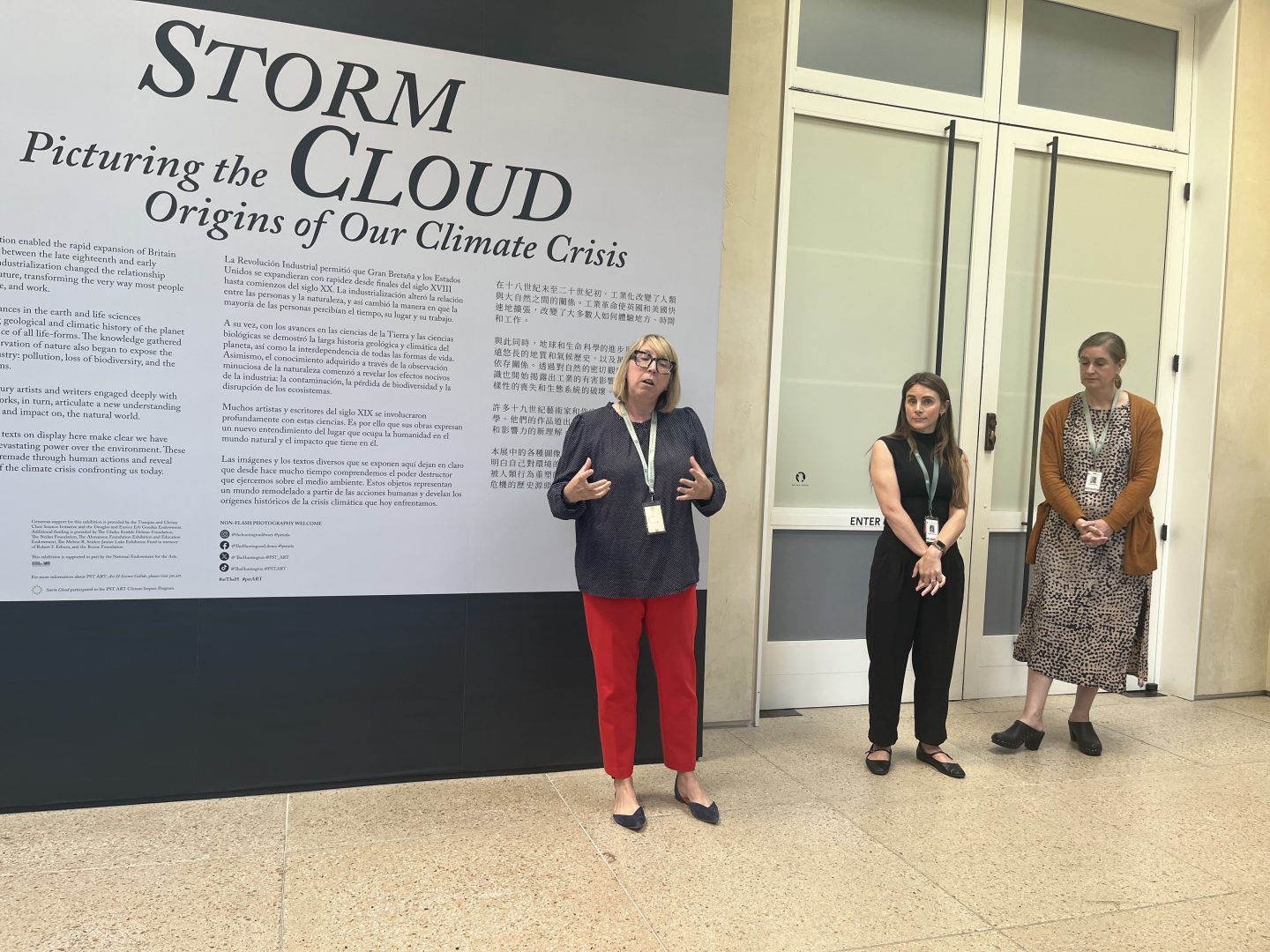

Co-curators Melinda McCurdy, The Huntington’s curator of British art, Karla Nielsen, senior curator of literary collections, and Kristen Anthony, assistant curator for special projects, talked about the exhibition by phone three days before the show.

Nielsen said, “When we were given the theme ‘Art and Science Collide,’ we knew we were going to initially use materials across the Huntington collections supplemented by key loans. We have materials by John Ruskin both in the museum and in the library and we started thinking about his process of close observation of the natural world.

“He gave a lecture in 1884 called ‘Storm Cloud of the Nineteenth Century’ in which he talks about decades of looking at the sky, thinking about the clouds, and drawing them. He referred to this new type of cloud ‘storm cloud,’ which today we would call smog – the cloud formation that happens around particulate matter from burning coal.”

“It’s considered one of the first public outcries about human-caused climate change and it happened in 1884,” pronounced Nielsen. “We thought it was interesting that it was much earlier than when most people cite the beginning of our conversation about how long have humans known in the developing world that we were having a harmful impact on the natural world.”

Anthony explained, “So when we talk about the origins of the climate crisis, it’s important that we look at the period immediately after the Industrial Revolution because that’s when in earnest the extraction and burning of fossil fuels for industry really took off. And literally the carbon in the atmosphere began to steadily rise throughout the period that this show covers.”

“Ruskin was our starting point, but we actually traced the phenomenon through the Huntington’s collection which is strong in the histories of the United Kingdom and the United States, so it really does follow the material from Britain and the United States – it is a story of the Anglophone world. Obviously there are other stories to tell that cover the rest of the world, but this exhibition focuses on England and the U.S.,” clarified McCurdy.

“The thing that connects London and L.A. is smog so the show moves from the British Empire and a coal-powered economy to the beginnings of our current petroleum-based economy,” Nielsen pointed out. “Of course that makes L.A. a global hub because it’s one of the leading sites of extraction for petroleum as early as the late 19th century.”

Asked about the visitor takeaway, Anthony replied, “As far as the history of climate crisis, I think visitors will walk away knowing that we’ve understood humanity’s impact on the planet longer than the average person thought. And these changes – this impact on the planet – can be charted in the cultural productions of the period. You can see the earth changing and how industry is impacting the planet through the works of art and literature and the historical and scientific texts produced in the period.”

In her introduction shortly before a walkthrough of the exhibition, McCurdy said the project started when the Getty announced the theme for this iteration of PST, which is ‘Art and Science Collide.’ It was originally displayed in a smaller space but as their work progressed during the pandemic, the show moved to the Boone Gallery.

The exhibition is divided into three parts and multiple sections. The first “A New Relationship to Nature” is centered on humans’ connection with the natural world shown through beautiful works of art.

McCurdy took visitors to the first room and stated, “We commenced this exhibition in the late 1700s with the rise of the Industrial Revolution when factories started drawing people away from the countryside to the city and people were disconnecting from nature because they were working indoors. They learned to appreciate nature in a different way. It started the rise of tourism – when people were going into nature for recreation and pleasure. People sought picturesque vistas, they climbed mountains, and walked through valleys looking for that connection to nature.”

“John Constable’s painting ‘View on the Stour Near Dedham’ is in fact not a natural landscape but a scene of industrial infrastructure in Eastern England,” described McCurdy. “The river was converted into a canal in order to transport grain from the interior of the country where it was grown and processed in the mill to then be distributed to urban markets. It’s a story of commodity; we’re going to hear a lot about commodity and shipping in the 19th century. In the painting he showed how the weather and atmospheric conditions could be used to convey emotion – this is a very emotional connection to the landscape.”

The exhibition’s other sections link the arts and science more explicitly. A selection of Constable’s “cloud studies” is juxtaposed with drawings of clouds by pioneering British meteorologist Luke Howard, demonstrating the shared interest in close observations of natural phenomena.

Manuscripts by William and Dorothy Wordsworth are placed alongside multiple guidebooks to England’s Lake District, which were geared to the English public’s growing interest in hiking as a form of recreation and respite from city life.

Nielsen expounded, “While William was known as a poet, he actually wrote a guide about the Lake District. We were able to borrow from the Wordsworth Trust in the Lake District two manuscripts by his sister Dorothy Wordsworth. She was a companion to William throughout his life, accompanying him on his inspirational walks through the countryside. She was also an astute describer of the natural world so we borrowed one of her journals which contained a description ‘encountering daffodils on a hill’ that’s very reminiscent of his ‘Daffodils’ poem: ‘I wandered lonely as a cloud That floats on high o’er vales and hills, When all at once I saw a crowd, A host of golden daffodils.’ The poem conveys the enjoyment of being in nature.”

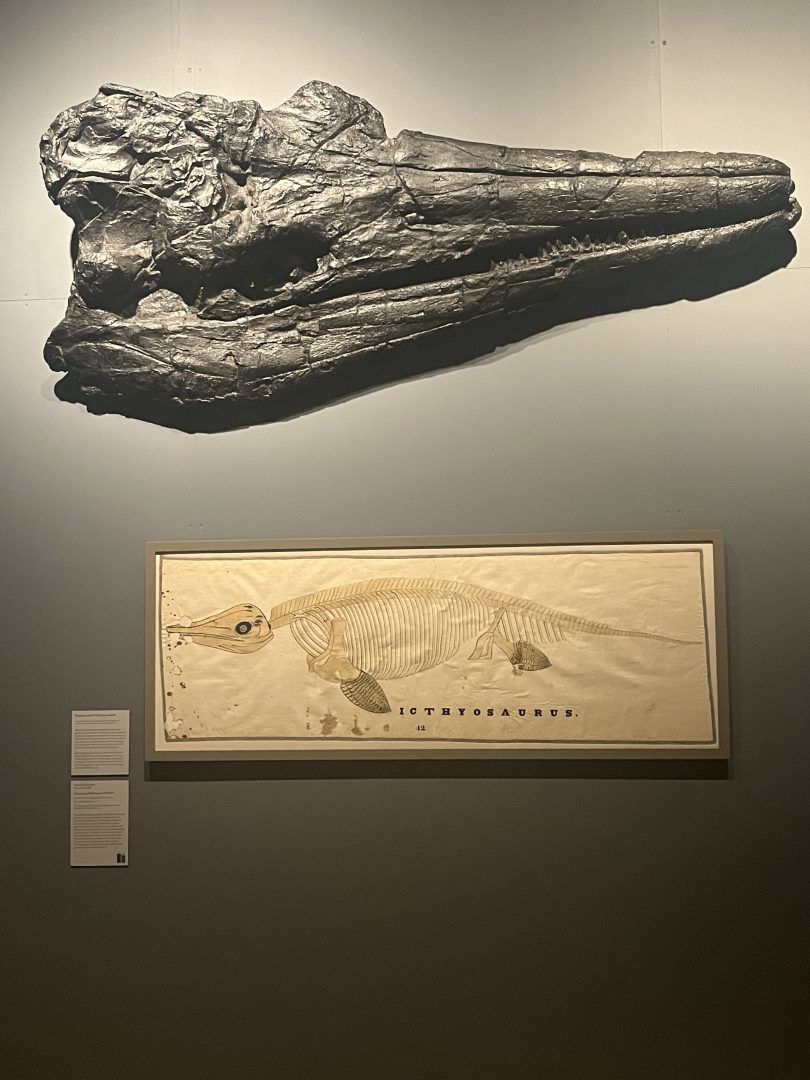

The history of science is explored in the next room. Anthony pointed to a research cast of ichthyosaur skull borrowed from the Dinosaur Institute, Natural History Museum of L.A. County and Bureau of Land Management. The animal which this skull belonged to was from 244 million years ago; the drawing of the ichthyosaur skeleton is by Orra White Hitchcock, wife of Edward Hitchcock.

“One of the materials in this room is a book published by James Hutton, a Scottish farmer and naturalist, also known as the founder of modern geology,” declared Anthony. “In 1788, he wrote the theory of earth which was the first work to postulate that the earth was much older than the popular understanding of earth’s age which was derived from a literal interpretation of biblical text. After looking at the layers of rock on his land and how they formed, he hypothesized the planet was millions of years old and so much older than what we had ever thought. We now know it’s 4.6 billion years old.”

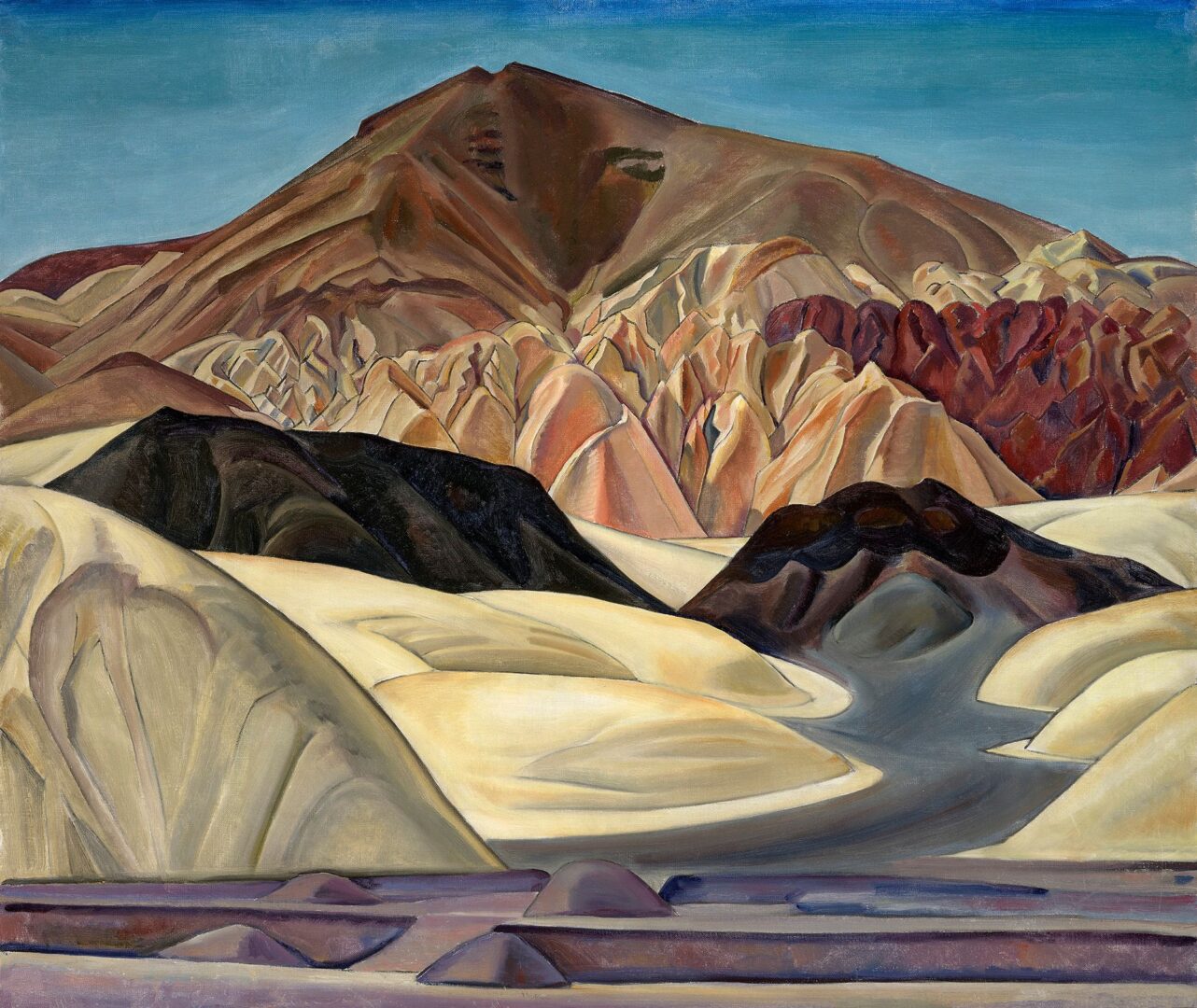

A broad range of objects traces growing environmental awareness over the course of the 19th century. Significant paintings by artists of the Romantic and Pre-Raphaelite movements and the Hudson River School are shown in conjunction with rare manuscript materials, such as Henry David Thoreau’s handwritten draft of Walden. Photographs of western American mountain ranges are displayed alongside materials from the archives of early 20th century conservationists John Muir and Mary Hunter Austin.

“Storm Cloud” also features artists known for their paintings of the Hudson River Valley scene in Upstate New York. Thomas Cole’s colossal “Portage Falls on the Genesee” – a gift to The Huntington in 2021 from The Ahmanson Foundation – pays tribute to the natural world as much as it cautions us about people’s effect on it.

The second section of the exhibition focuses on the problems that come with industrialization. Using a painting that depicts Jamaica, McCurdy discussed the plantation economy and the ecological damage that results from it – the extraction of resources and devastation that goes along with degradation of humanity.

Frederic Edwin Church’s “Vale of St. Thomas, Jamaica” shows the relationship between people and the industrializing world. On the right side of this painting, he portrays Jamaica as an untouched paradise with a very lush jumble of nature; but the left side, almost hidden by a storm cloud, illustrates evidence of severe drought exacerbated by deforestation due to plantation agriculture.

The other section of the room shows factory labor and some textiles and wallpapers produced by William Morris. McCurdy pointed out that Morris veered away from factory work and instead advocated for the artisanal way of manufacturing. One of the treasures in The Huntington’s collection is a book containing recipes for the dyes made from plants and vegetables used in his textile factories to ameliorate some of the problems causing harm to the environment.

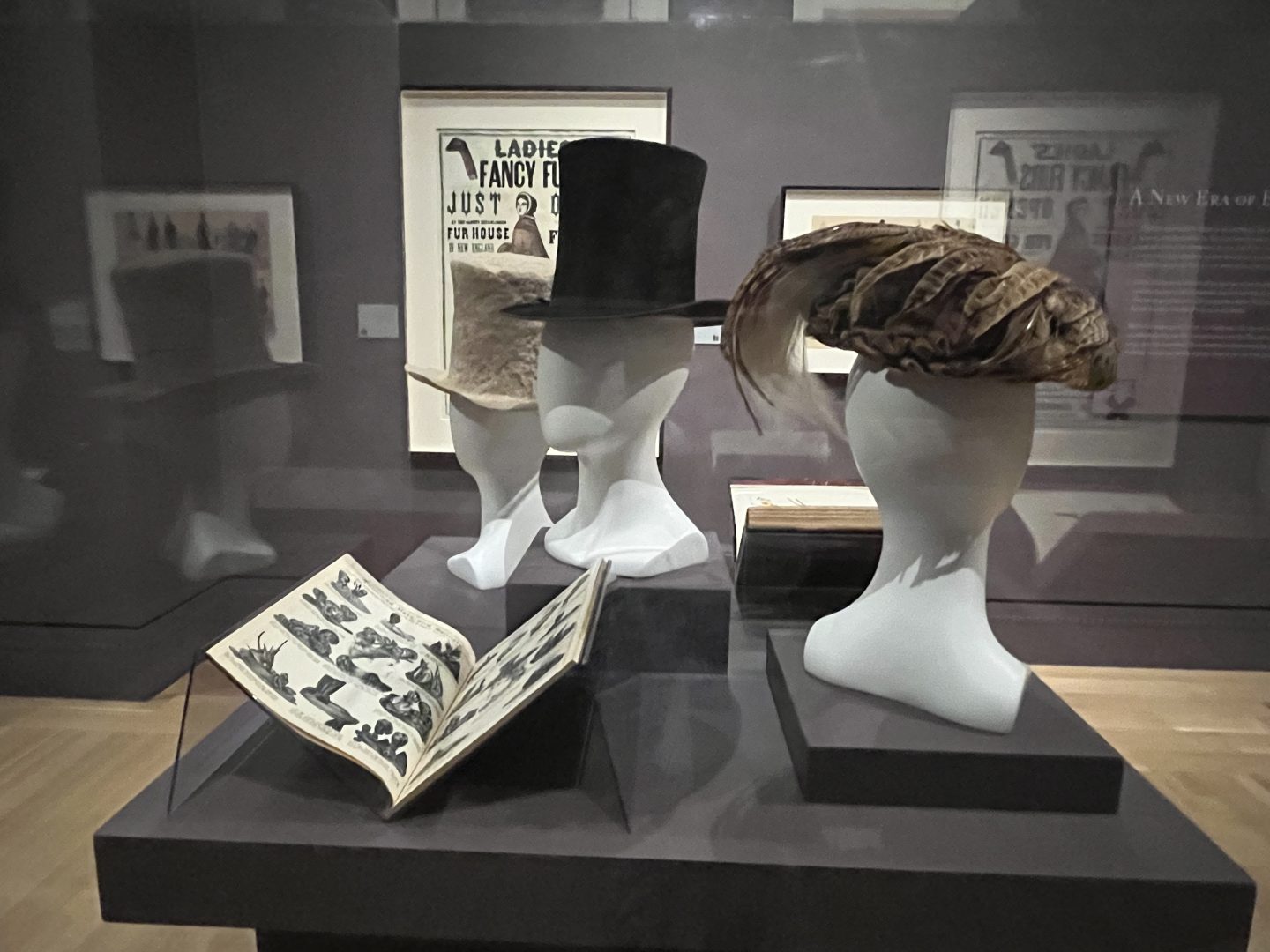

Impacts of fashion on the environment are displayed in the next room. The rate of extinction accelerated in the 19th century due to habitat destruction, overhunting, industrial pollution, among other factors. As this case shows, fashion was a major contributor as well. The hats which most gentlemen wore were made from beaver fur. Early in the 19th century their population was in such a deep decline that environmentalists were worried they were going to be extinct. The introduction of silk plush in 1840 saved beavers from that fate. Gentlemen decided they preferred the more shiny look of silk plush so it became a trend and the beaver population began to recover.

Late in the 19th century, around 1888-1890, women’s hats using bird body parts became a trend. This extreme hunting brought many birds like egret and bird of paradise to near-extinction. A group of upper-class women decided to counter that by convincing their friends to move away from this fashion trend. That organization turned into the Audubon Society. It was one of the earliest wildlife preservation organizations specifically to protect animals from being hunted for fashion and it was able to lobby the government to enact laws that protect migratory birds.

The final section focuses on the extraction and burning of coal into oil and the exhibition displays paintings of factories blowing black smoke into the atmosphere – images meant to signal production and progress.

Materials from the Ruskin collection illustrate London as one of the most polluted cities in the world. McCurdy disclosed, “The air quality was so bad and the people called it ‘fog’ and ‘pea souper’ because of its sickly green yellow color which was essentially particulates from coal-burning fires in factories mixed with the water in the air, creating a dense atmosphere.”

“London and Los Angeles are connected by smog,” reiterated McCurdy. “Many of those who grew up here remember we had days when we weren’t allowed to go outside because of the bad air quality. It has gotten better with regulations; collective action and regulations help ameliorate these problems.”

The final work of art is a video installation by L.A. based artist Rebecca Méndez. She spliced together images of different times of the day to illustrate that our sky is a shared space and we all breathe what we throw into it. The curators used it as a 21st century cloud study.

As a parting note, Anthony shared with us The Huntington’s participation in the Climate Impact Program. They created a show that has as little adverse effect as possible and modeled sustainability practices: they reduced their research travel and limited loans to a few geographic regions and institutions so shipments could be bundled together. Within the gallery itself they mixed cases and frames from existing inventory – nothing was customized; instead of building walls with Sheetrock they used apple plywood panels so they could be disassembled and utilized for future exhibitions. They will also produce a climate impact report.

“Storm Cloud” examines a critical issue in a fascinating way that captures our attention. Anthony, McCurdy, and Nielsen did an extraordinary job in turning an otherwise lecturing tone into one that encourages us to take an active role in reversing climate change lest future generations end up inheriting a planet that’s barely recognizable as the same place their ancestors inhabited.