Originally published on 15 January 2019 in the Pasadena Independent, Arcadia Weekly, and Monrovia Weekly

Qianjiao Ma, known to her friends as ‘Q,’ is a long way from her birthplace in Northern China but is very much at home in her adopted city of Arcadia. She is one of twelve ‘Illustrators of the Future’ winners to be honored during the 35th Annual L. Ron Hubbard Achievement Awards at the Taglyan Complex on Friday, April 5, 2019.

The highlight of the ceremony will be the announcement of the year’s two Grand Prize winners – a writer and an illustrator – who will each receive $5,000. Quarterly winners, like Ma, also receive cash prizes from $1,000 to $500. Their winning stories and illustrations will appear in the annual anthology ‘L. Ron Hubbard Presents Writers and Illustrators of the Future’ Volume 35.

An international competition, ‘Illustrators of the Future’ is considered the most enduring and influential contest in the field of science fiction and fantasy. Artists worldwide participate in this competition and they are judged by professional artists, some of whom are masters in the genre.

To get to the heart of how Ma arrived at this momentous stage in her chosen profession, it helps to know what drives this determined young woman.

“I was born in Shenyang in Northern China,” begins Ma. “In my senior year in high school I went to Beijing to investigate what school I could go to and get training. I have always been interested in art so I could have gone to a well-known arts academy in China. But my mom also asked me if I wanted to study abroad. It was an exciting prospect as I discovered that Beijing was vastly different from the city where I came from and it made me realize that I really wanted to see the world.”

Continues Ma, “I arrived in Los Angeles in 2008 and I attended Santa Monica College. One year later, my mom, who lives in Seattle, asked me to move there and I did. I went to Bellevue Community College for a year but I found their arts offerings quite limited.

“A friend mentioned ArtCenter College of Design in Pasadena, so I decided to visit the school. When I got there, I saw students were sleeping on the sofas in the hallway; they had worked all night on projects and didn’t have the time to go back to their dorm. The artwork displayed at the gallery were amazing, a far cry from anything I’d seen in Bellevue!

“I was convinced I had to go to that school; I applied but was rejected the first time around. While there are other entertainment design schools in California because the movie studios are here, ArtCenter is the Number One school for that discipline, so it was where I wanted to be. I prepared my portfolio again, resubmitted it, and was accepted on my second try.”

While attending ArtCenter College of Design from 2012 to 2016, Ma held freelance posts and various internships. She describes, “I interned for BRC Imagination and was one of the artists involved in the 2015 redesign of the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame Museum in Cleveland. It was at BRC that I gained training in experience design, which became my forte.

“After college I wanted to pursue experience design work but couldn’t find any opening. Not wishing to be unemployed, I worked as a comic book illustrator at Stela Unlimited, which is an app for smart phones. I was the background concept artist for a graphic novel called Lumi White, a remake of Snow White.

“I still really wanted to go into experience design, though, and that opportunity came six months into my stint at Stela. A spot opened up in a small company called Steadman Design Studio which creates immersive entertainment experiences for theme parks, attractions, exhibits and shows.

“From Steadman, I moved on to Thinkwell Group, which is a larger outfit. I had the chance to work on museum, restaurant, casino, and theme park design including Warner Brothers Abu Dhabi, the largest indoor amusement park in the world. It was a lot of fun – I was able to try out different aspects of experience design; I conceptualized the entrance ticketing area, the art deco-style Bugs Bunny, and various murals inside. It was an absolute thrill to see my designs get built!

“A year later, an acquaintance of mine at a company called ShadowMachine approached me to do animation design. I started working at ShadowMachine in February of last year and I’m enjoying doing animation.”

Throughout her career, Ma has been driven by that same passion students demonstrated which made such a profound impression on her when she visited ArtCenter years ago. She continues to look for ways to learn and expand her knowledge. She was a designer and painter for the Netflix Original ‘Disenchantment’ and TBS’s ‘Final Space.’ She was one of the featured artists to share their views on theme park design in ImagineFX magazine, and was included in Graphite magazine on traveling sketches.

An accomplished plein air painter, Ma has exhibited her work in various Los Angeles galleries. She recently did illustrations for the magazine ‘Compound Butter Issue One: Junk Food.’ She is being included in the upcoming sci-fi design tutorial ‘Beginners’ Guide to Sketching: Robots, Vehicles & Sci-Fi Concepts.’

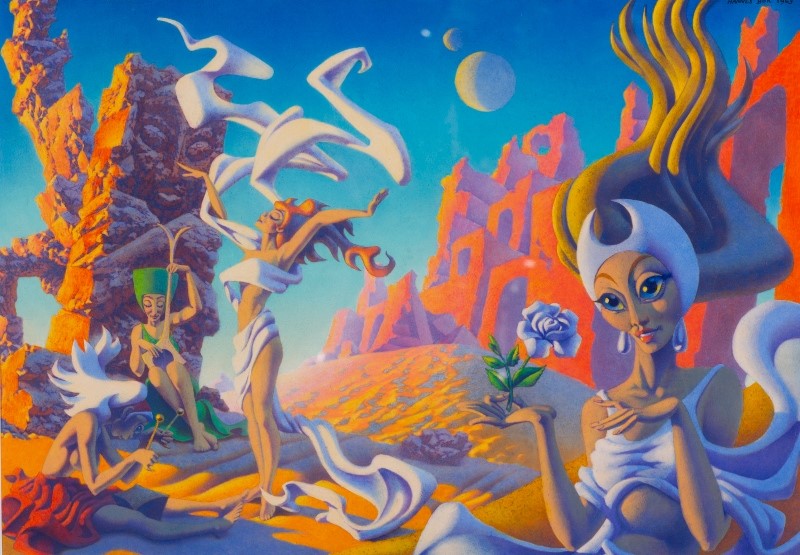

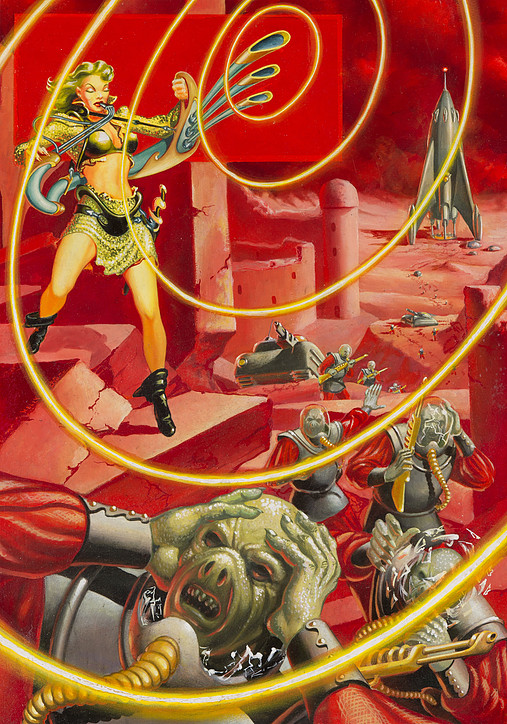

Last year, Ma found out about the ‘Illustrators of the Future’ worldwide contest and right away she sent three entries – Ruins, Apocalyptic World, and Space Ship Inter(ior Design). After winning the quarterly competition, she was paired up with a writer.

“I can’t disclose details about the novel other than it happens in the post-apocalyptic world,” states Ma. “I depicted the harsh environment to which people are exposed, where chips are embedded in their brains as a means of controlling them.”

“This is my first time illustrating a novel and even if my work doesn’t earn the grand prize, I feel that I’ve learned so much already. I met people whose perspectives are different from mine,” adds Ma. “Should I win, I would be quite ecstatic! It would prove that I made the right decision on how to illustrate the writer’s idea and that I’m ready for more book designing.”

Winning the Grand Prize would indeed take Ma’s career into another realm. John Goodwin, president and publisher of Galaxy Press which is the exclusive publisher of the winning books and illustrations, confidently says, “After 35 years, we’ve had close to 800 winners. Several of today’s best known fantasy and science fiction writers and illustrators got their start from winning the ‘Writers and Illustrators of the Future’ competitions.

“Many past winners are now recognized names – Patrick Ruthfuss, one of the top-selling fantasy authors in the world today; Brandon Sanderson; Sean Williams; Eric Flint, the biggest fantasy author in Australia; Nnedi Okorafor, of Nigerian descent, now one of the main writers in the Black Panther Universe; among many others. Canadian writer Robert Sawyer is one author who didn’t actually win, but it was the judges who gave him critique that helped advance his writing; he has gone on to become Canada’s most successful science fiction writer.

Goodwin continues, “Part of their success in becoming known to the general public is that we arrange publicity for the winners of the writing and illustration competitions. They get written about in various news outlets, appear on TV shows, do book signings in bookstores, and attend conventions like Comic-Con International and Dragon Con to promote their books. We continue to support them in their career. If they publish new books, we let them bring those as well. That’s why these two contests have enjoyed such longevity.

“And because it’s free to enter, we attract a large number of competitors from all over the world. We received entries from over 175 countries in Africa, South America, Central America, and throughout Europe. For the illustration contest, they don’t have to speak English since they’re only drawing pictures. This year we have several winners with Chinese, Japanese, and Korean names but we don’t have the information on whether they were born there or if they’re children of immigrants. An unprecedented five writers and illustrators from the United Kingdom won this year.”

Pairing the writer with the illustrator is done by the editor, according to Goodwin. “There is no standard for what illustration an artist can send us. Some of them do oil, others do pencil, many do computer-generated images. Sometimes we look at their choice of medium to figure out which book would work with it best. But we also try to make complementary matching – we pair up a fantasy writer with an illustrator who reads fantasy books, for instance.

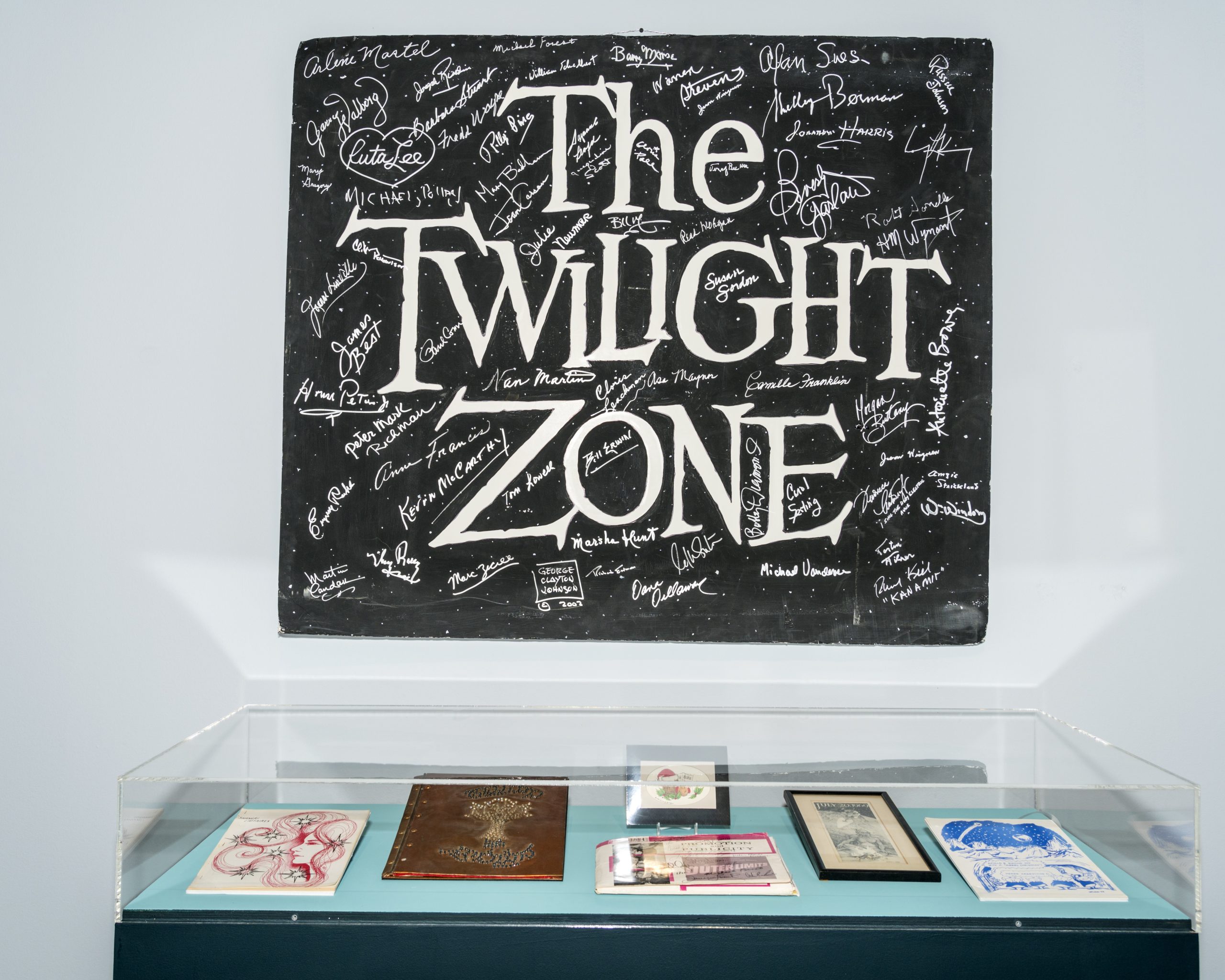

“Judges are established professionals in the industry including: Larry Elmore, known for his illustrations for ‘Dungeons & Dragons,’ ‘Dragonlance,’ and his own comic series ‘Snarfquest;’ Gary Myer who is an illustration professor at ArtCenter College of Design in Pasadena; Stephan Martiniere, who did the design work for Disney’s ‘Frozen,’ ‘Suicide Squad,’‘Aquaman,’”

Goodwin explains the history of the contest, “While L. Ron Hubbard was widely known for his work in Dianetics and Scientology, he was also one of the most prolific writers in America in the 1930s and 1940s, having written over 200 western, mystery, adventure, science fiction, fantasy, and romance books using his own and 15 different pen names.

“As a young man, he had traveled to Guam and as far as China back in the 1920s, and wrote about his experiences. In fact, he took the first photo of the Great Wall of China, well before it was a tourist attraction, and sold it to the National Geographic. That was the first picture Americans had ever seen of it.

“Towards the end of Mr. Hubbard’s writing career he turned to fantasy and science fiction. When he was in Alaska in 1978, he initiated the ‘Golden Pen Award’ to celebrate his 50th year as a writer. It was the precursor to the ‘Writers of the Future’ Award which he launched in 1983 as a means to discover and nurture new talent in science fiction. Five years later, ‘Illustrators of the Future’ was created to provide artwork for the books.”

“He set up an endowment from his personal earnings and royalties from his books,” Goodwin goes on to say. “When he passed away in 1986, he directed in his will that the writers and illustrators contests continue. Galaxy Press was established as the exclusive publisher of the ‘Writers of the Future’ contest winners and all the fictional works of L. Ron Hubbard.”

Arcadia’s Qianjiao Ma is one of the many beneficiaries of L. Ron Hubbard’s bequest. On April 5, she’ll find out if her already burgeoning career will also be catapulted into another world.