Also published on 13 November 2025 on Hey SoCal

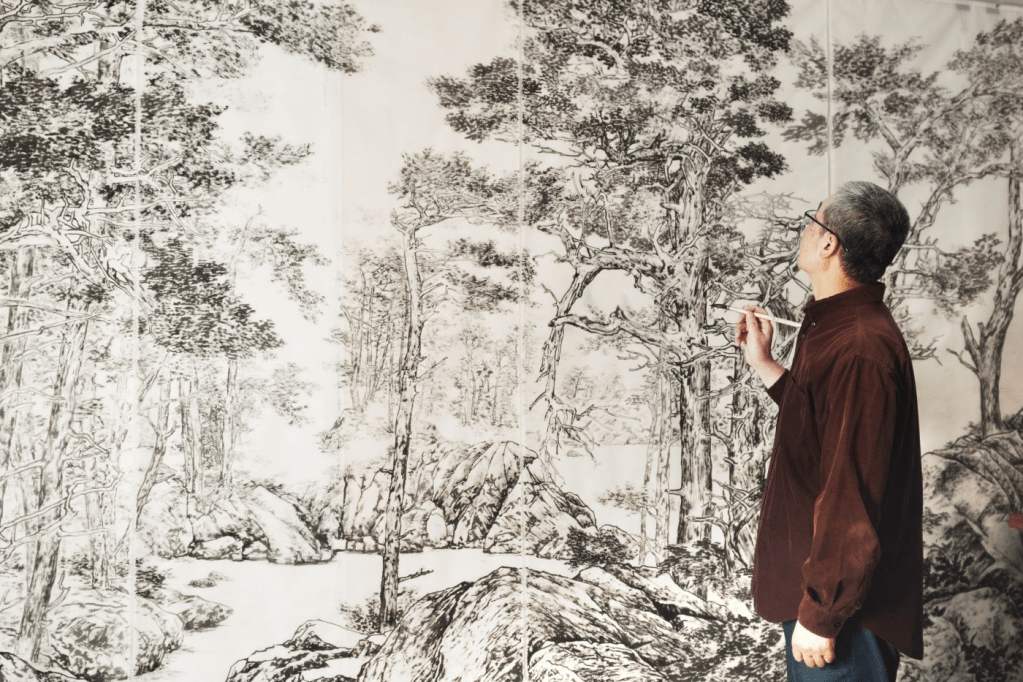

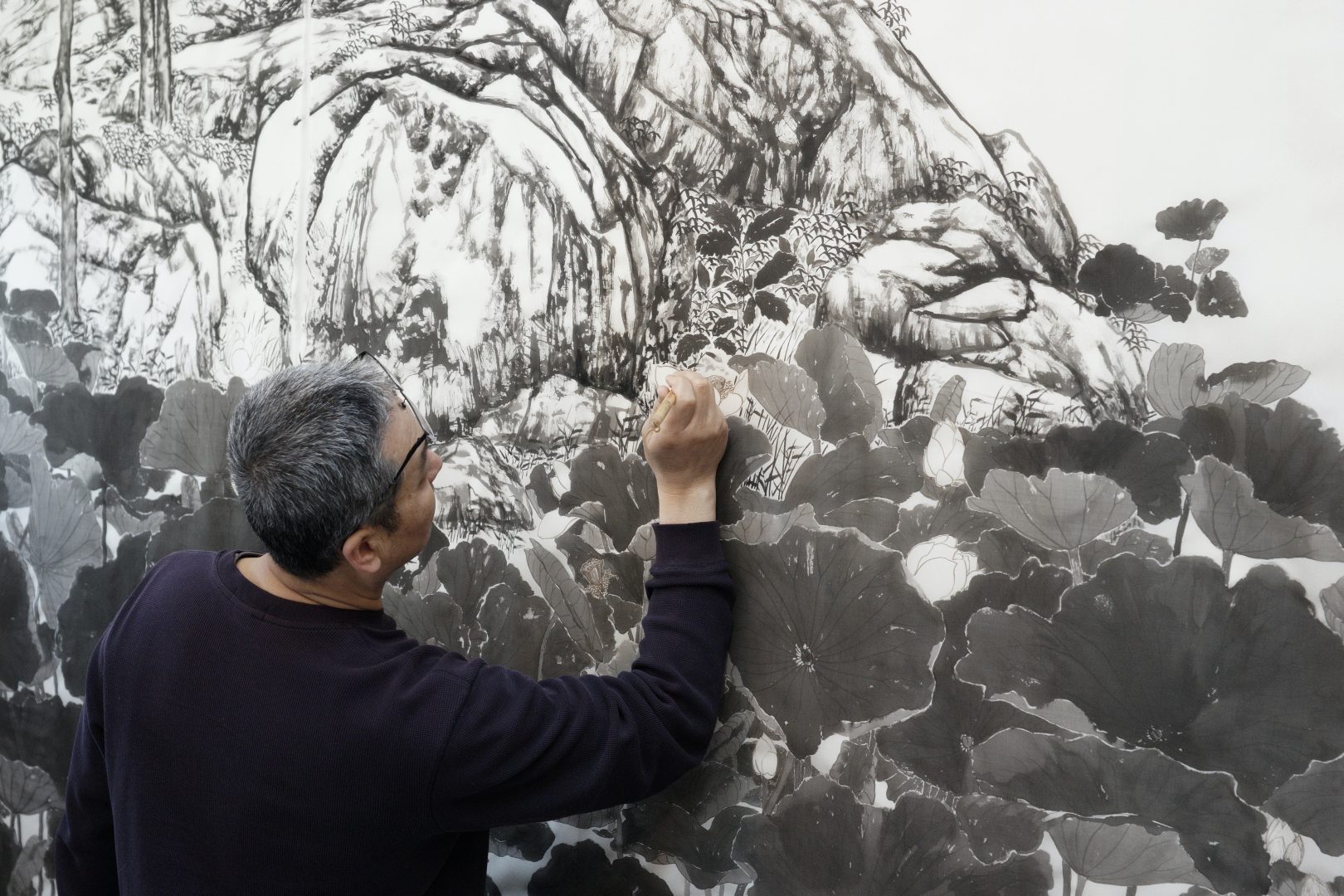

Installation photo courtesy of The Huntington

“Radical Histories: Chicano Prints from the Smithsonian American Art Museum,” makes its West Coast debut at The Huntington’s Marylou and George Boone Gallery from Nov. 16 to March 2. Curated by E. Carmen Ramos, forming acting chief curator and curator of Latinx art at the Smithsonian American Art Museum, the exhibition features 60 dynamic works by nearly 40 artists and collectives that trace more than six decades of Chicano printing as a form of resistance, community building and cultural reclamation.

Commencing with the late 1960s Delano Grape Strike, the precursor to the United Farm Workers (UFW) labor union, the prints in “Radical Histories” depict momentous events in the history of community activism and the formation of collective identity. Chicano artists used silkscreens, posters, and offset prints to mobilize communities – often with barbed wit, lively colors, and evident urgency.

The exhibition is arranged in five thematic sections: “Together We Fight,” “¡Guerra No!” (No War!), “Violent Divisions,” “Rethinking América,” and “Changemakers.” Each section highlights how Chicano artists have used the accessible and reproducible medium of printmaking to confront injustice, affirm cultural identity, and engage in transformative storytelling.

Section 1: Together We Fight

The opening section explores how the UFW, cofounded by César Chávez and Dolores Huerta, collaborated with visual and performance artists to support the fight for farmworkers’ rights. Key labor actions inspired a wave of Chicano art that functioned as both political expression and tangible solidarity. Artists adopted the UFW’s iconic black eagle, embedding it in posters, prints, and murals that raised awareness and helped fund the movement. The union’s visual language extended beyond its own campaigns, appearing in advocacy materials for the Texas Farm Workers Union and the Cannery Workers Committee in Sacramento.

Section 2: ¡Guerra No! (No War!)

Since the 1960s, Chicano graphic art has played a vital role in advancing antiwar resistance. These works serve as rallying cries, counternarratives to mainstream media, and spaces of reflection. Chicano artists have used print and poster art to critically examine U.S. military interventions in Vietnam, El Salvador, Chile, Iraq, and elsewhere.

Section 3: Violent Divisions

The U.S.-Mexico border has been a central theme in Chicano art. Printmaking has enabled Chicano artists to raise awareness about the experiences of immigrant communities because it is affordable and prints are easily distributed. Recurring iconography – such as the monarch butterfly, a symbol of natural migration – challenges the notion of geopolitical boundaries. Figures like the Virgin of Guadalupe and ancient Mesoamerican goddesses appear as powerful cultural symbols.

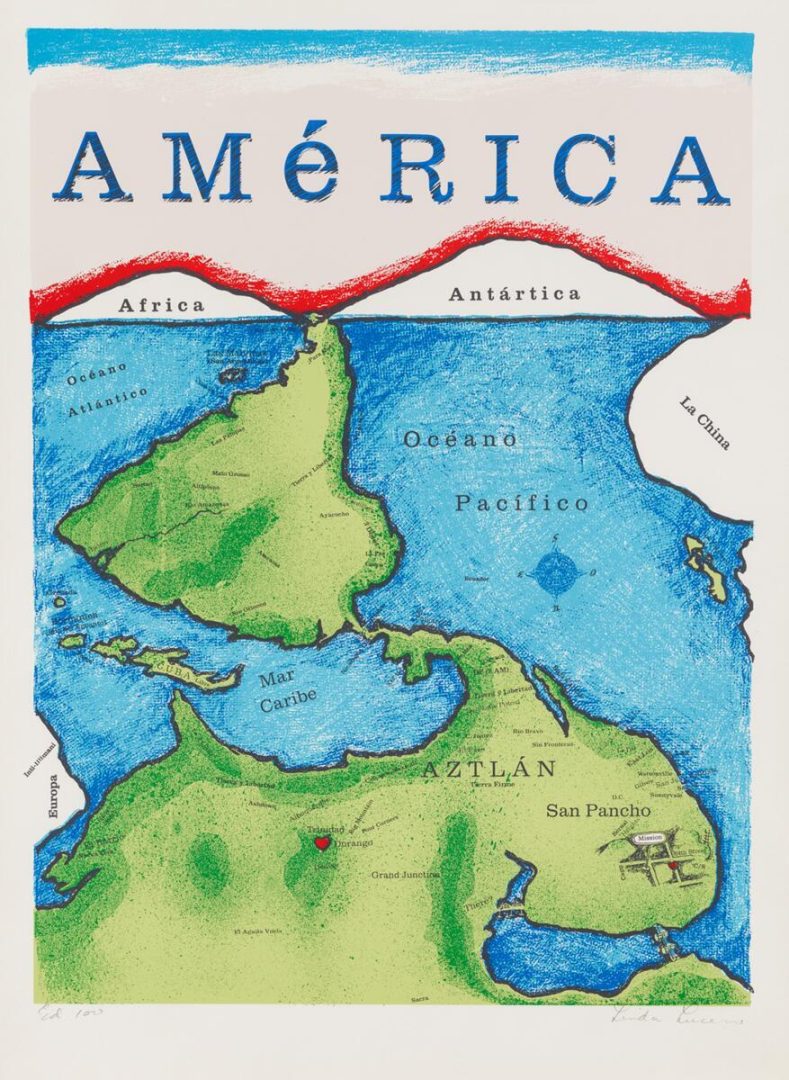

Section 4: Rethinking América

This section presents works that broaden historical narratives by including perspectives rooted in resistance and cultural reclamation. The artists drew inspiration from revolutionary figures and movements to create narratives that center Mexican American and Indigenous perspectives. Using mapmaking and record forms like the ancient Mesoamerican codex, Chicano artists also created speculative past and present narratives to reimagine social landscapes.

Section 5: Changemakers

Portraiture is a cornerstone of Chicano art, used to educate audiences and celebrate both cultural icons and overlooked figures. Artists often base their portraits on documentary photographs, transforming black-and-white images into vivid prints that honor the subject’s life and legacy. Featured changemakers include political prisoners, activist leaders, attorneys, actors, and artists—individuals who challenged the status quo and shaped history.

By email, Dennis Carr, Virginia Steele Scott Chief Curator of American art, and Angélica Becerra, Bradford and Christine Mishler Associate Curator of American Art – also the venue curators – discuss the exhibition’s origins, its relevance, and viewer takeaways.

“Radical Histories was organized by the Smithsonian American Art Museum to highlight the central role Chicano artists have played in shaping American visual culture,” begins Carr. “The exhibition began touring nationally in 2022 following its debut at the Smithsonian American Art Museum, and The Huntington is presenting its first West Coast exhibition.”

“While the core exhibition is drawn from SAAM’s collection, our presentation places particular emphasis on Los Angeles as a vital center of Chicano printmaking,” Carr clarifies. “To honor that history, The Huntington commissioned a new mural by Los Angeles–based artist Melissa Govea, created in collaboration with Self Help Graphics & Art, a community print studio that has supported Chicanx and Latinx artists since 1973.”

“Through this partnership, we commissioned Melissa Govea, a Los Angeles–based artist who is Chicana and Purépecha,” explains Carr. “Govea began her career as a muralist and is known for work that honors community, ancestry, and cultural memory. Rather than giving her a specific direction, we invited her to respond to the themes of the exhibition. The result is a dedicated gallery featuring a new mural, a sculptural installation, and print-based works that together reflect multiple dimensions of her practice. This marks the first time her work has been presented in a museum context.

“Her mural, titled ‘Sangre Indígena’ (Indigenous Blood), draws on portraits of friends, collaborators, and cultural leaders who have shaped her life. The work recognizes the generations of artists, organizers, and knowledge-keepers who came before her, while affirming the presence, agency, and creativity of those shaping Los Angeles today.”

It would be an oversimplification to say how many works in the exhibition are from L.A. artists, as Becerra explains.

“Many artists in ‘Radical Histories’ have deep ties to Los Angeles, whether they lived, studied, printed, organized, or collaborated here. The most meaningful connection is through Self Help Graphics & Art, which offered open studio access, mentorship, and a collaborative printmaking environment to generations of Chicano and Latinx artists.

“Artists such as Barbara Carrasco and Ernesto Yerena Montejano continue to live and work in L.A., and their practices remain rooted in local community networks. So rather than thinking in terms of birthplace alone, it’s more accurate to say that Los Angeles is one of the central homes of Chicano printmaking, and the exhibition reflects that history.”

Asked if the exhibition has taken greater meaning now with ICE raids targeting Hispanic communities and looking Hispanic or Latino is enough to get one handcuffed and thrown into a detention camp, Becerra replies, “The themes in ‘Radical Histories’ are both longstanding and timely. Chicano printmakers have historically used posters and prints to address labor injustice, state violence, displacement, and the struggle for belonging – issues that continue to resonate today.”

Becerra says further, “What museums like The Huntington can offer is space: a place to look closely, process, reflect, and connect personal experience to shared history. These works remind us that art has always been a tool of community care and resistance.”

As for the viewer takeway, Carr states, “We hope visitors come away with a deeper understanding of how Chicano artists have used printmaking to organize, to tell stories, to build community, and to assert cultural identity. And we hope they see that art is not separate from daily life – it is a tool for resilience and collective meaning-making.”

“In addition to the exhibition itself, The Huntington will host public programs, bilingual gallery talks, and hands-on workshops in collaboration with local artists and partners,” adds Carr. “A major highlight will be Historias Radicales: Latinx Identity and History in Southern California, a two-day conference on December 5–6, connecting the exhibition to The Huntington’s co