Also published on 3 September 2025 on Hey SoCal

Image courtesy of M. G. Rawls

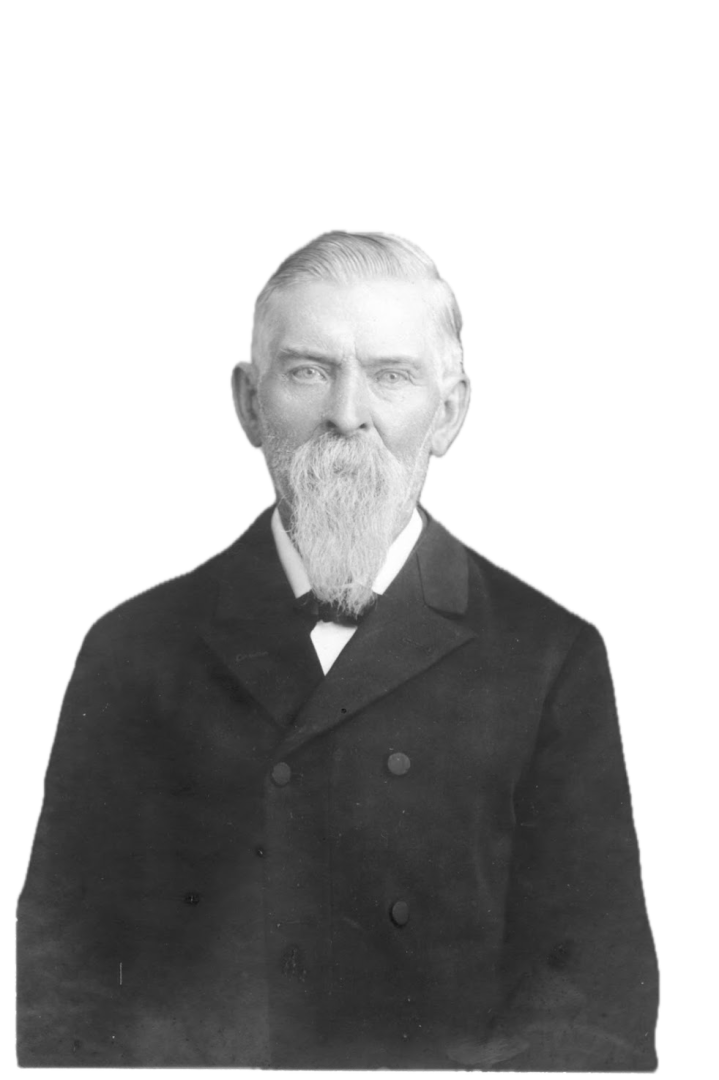

Public executions aren’t exactly pleasant subjects to write a book about. But for M.G. Rawls, a retired Pasadena lawyer and author of the young adult fantasy trilogy “The Sorts of Pasadena Hollow,” it was a compelling topic that had captivated her for decades. Rawls’s great-great-grandfather, James Madison Anderson, was the El Dorado County sheriff who carried out one of the last public hangings in California towards the end of the 1880s. For years, the thought that an injustice might have been done weighed heavily on him.

In her book “Hanging Justice,” scheduled to publish in October, Rawls delves into this event and gives readers an intimate look at the victim, the killers, the crime, and the hangings. She chronicles the details of the case and then reaches her own conclusions about this long-forgotten and rarely discussed episode in Placerville’s past. She will give an author book talk sponsored by the El Dorado Historical Society on Friday, October 17 from 6 to 7:30 pm at the Morning Star Lodge (also known as the Odd Fellows Lodge) in Placerville.

Based on newspaper articles at the time, a reputedly wealthy farmer John Lowell was murdered on March 24, 1888 during a robbery at his ranch near Mormon Island in El Dorado County. Three men were convicted of first degree murder – John Henry Meyers, a 27-year-old immigrant from Germany; John Olsen, a 24-year-old Norwegian native immigrant; and William Drager, a 41-year-old immigrant from Germany.

Meyers was hanged on November 30, 1888, but Olsen and Drager’s execution on the same day was stayed pending appeal. Coverage of the arrests, trial, and hangings was a local sensation. Dozens of newspaper articles ranging from the Sacramento Bee to the San Francisco Examiner recounted the gory details. Hundreds of spectators observed Meyer’s hanging, that gave it a circus-like atmosphere.

Olsen and Drager – who steadfastly claimed throughout the trial that they weren’t involved in the plot to kill Lowell – were hanged on October 16, 1889. Sheriff Anderson limited the observers to the minimum required by law and had canvas draped over the courtyard to keep out as many prying eyes as possible.

Hangings were not uncommon in the United States back then; Placerville had been referred to as “hangtown” since the Gold Rush days. However, Olsen and Drager’s sentence galvanized the whole town into action because Placerville residents felt they had not been complicit in the murder, and the death penalty was too harsh for their actual crime.

Over 425 townspeople – including the district attorney who prosecuted the case, the sheriff, and nine of the 12 jurors – signed a petition requesting the sentence be reduced to life imprisonment.

The men had been model prisoners and were ready to accept their fate. Moreover, the victim – John Lowell – allegedly was of dubious character, having made many enemies and was himself accused of murder just a couple of years before. Olsen and Drager’s attorneys worked diligently to save them, even hand-delivering the petition and request for a pardon to Governor Waterman in Sacramento. Still, the petition was rejected, and the pardon turned down. For a long time, the townspeople wondered whether Olsen and Drager should have been executed.

Rawls’s grandmother had previously written about this event; but she was determined to find out more. She scoured through hundreds of old newspapers online and did extensive research at the Huntington Library in San Marino, the El Dorado Historical Society, the Center for Sacramento History, and the California State Archives. She traveled to Auburn, New Hampshire, to look at family documents and photos that her aunt and uncle have meticulously preserved.

By email, Rawls talks about what made her author “Hanging Justice,” what she learned from her exhaustive investigation, and the reader takeaway.

“In 1970, my grandmother wrote a community college paper about the last hangings in El Dorado County in 1888 and 1889 for which she got a B+,” recounts Rawls. “She’d played with a small model clipper ship called the Mountain Queen, crafted by two of the three hanged men while they were in jail. Sailors by trade, the two men made the miniature ship for her grandfather, my great-great-grandfather, Sheriff James Madison Anderson. It was their way of thanking him for taking care of them while their appeals were pending. They looked up to him like a father, yet he would be the one to hang them. My grandmother gave me the Mountain Queen, and I display it on a table in our living room as a relic of the event.”

It would take a while, though, before Rawls started writing the book. She discloses, “I’d had the story in my head for years, as I’m guessing many writers do, but didn’t start in earnest until about four years ago, just after I’d finished writing the third book in a young adult fiction shape-shifting trilogy – a series which combined my love for the local animals with California history. It was a natural transition for me since I love history and had experience doing research with my fiction books.”

Asked if the event haunted her family, Rawls replies, “I know that Sheriff Anderson and Marcus Bennett were emotionally torn about the executions of two of the men. Both felt that these men should have received a life sentence instead of death. Other than that, except for my grandmother, who was probably more intrigued than haunted, I don’t know what the rest of my family thought. But for the model clipper ship and my grandmother’s college paper, it is doubtful this story would have survived.”

In the course of her investigation, Rawls learned a few things that she hadn’t previously known and unearthed some personally meaningful finds.

“I knew that my great-great-grandfather, James Madison Anderson, was sheriff of El Dorado County from 1886 to 1890, so I was aware that he was generally in charge of the men,” states Rawls. “Still, I didn’t fully understand his specific role in the hangings until I read the contemporary newspaper accounts. Furthermore, until I started researching, I didn’t grasp that it was my great-uncle, Marcus Percival Bennett, Sheriff Anderson’s son-in-law, who was the district attorney prosecuting the case. I can only imagine the discussions that the two men must have had over the trial and hangings.”

“There were many surprising discoveries, made possible through the numerous institutions that I visited, family members who opened up their collections, and the hundreds of newspapers I pored over online,” Rawls continues. “I learned that the ‘victim,’ farmer and rancher John Lowell, was hated by many, and there were probably dozens who wanted to see him dead. But of course, you take your victim as you find him. I also learned that the State of California keeps all the files in death penalty cases and that anyone can access them in person through the California State Archives.”

“And lucky for me, despite a fire that burned down the El Dorado County courthouse in 1910, the El Dorado County Historical Museum had the preliminary examination records and original exhibits” adds Rawls. “While most of the records at the museum were in cursive and at times challenging to read, nonetheless, holding these documents, I found myself transported back to the period.”

The fantasy novels Rawls previously penned flexed her imagination and creative thinking. Writing a historical non-fiction, it seems, proved to be an adventure that was just as fun and pleasurable for her.

“While I did a lot of research for my fiction books, ‘Hanging Justice’ necessarily required exponentially more,” Rawls reveals. “Still, the research institutions and historical places visited and friends made along the way more than made up for the time spent. Plus, I like researching. For me, it’s detective work – with bits and pieces in various sources to be put together like a puzzle.”

Although that’s not to say that it was without its challenges. Declares Rawls, “This is my first non-fiction book, so accuracy was necessary. Besides, while it’s unconventional, I was determined to use footnotes instead of endnotes so the reader wouldn’t have to keep turning to the back. I’ve tried to make the story interesting, too.”

Writing “Hanging Justice” was a revelatory experience for Rawls as well.

“Placerville is known as ‘Hangtown’ for the vigilante-driven hangings that occurred during the gold rush period, starting in 1849, after the discovery of gold by James W. Marshall in nearby Coloma, California, the previous year,” Rawls explains. “’Hanging Justice’ includes the telling of a particularly abhorrent hanging in 1852, when an ‘assemblage’ stormed the jail in Coloma and two men – one white and one black – were forcibly taken and hanged. The original account is in the El Dorado County Archives at the Huntington Library.”

“As highlighted in my book, the hangings for the killing of John Lowell were not the result of vigilantism,” clarifies Rawls. “They were legal executions after due process of law. Plus, like my great-great grandfather and great-uncle, many of the townspeople did not want two of the men to be executed. In my view, despite the circumstances surrounding these last hangings, Placerville had transformed into a lawful community and was determined to give these defendants a proper trial. The trial transcript in this case was over 600 pages, and the three men were represented by Placerville’s finest. Though in the end, Placerville’s best wasn’t good enough.”

This book isn’t your everyday read but Rawls thinks there’s valuable takeaway for someone who buys and peruses it.

“‘Hanging Justice’ lays bare the factual and legal groundwork for what happened,” Rawls describes. “But I hope the book also allows the reader to reach their own conclusions as to whether justice was rendered by the hangings. Personally, I found the victim’s own trial for murder several years earlier and the legal issues surrounding two of the men’s appeals fascinating. But then I’m a bit of a nerd when it comes to history.”

“Family stories worth keeping can be very fragile and will disappear if not written down,” pronounces Rawls. “The process of saving them can be both unifying and rewarding. In my case, despite the dark topic, this story has brought me together with cousins and friends I didn’t know I had, including the townspeople of Placerville. So I would urge readers to pursue their own family stories.”

During her countless trips to Placerville, Rawls learned that residents there today didn’t know about this particular event. As she worked on her book, she made it her mission to uncover all the documented facts so she could retell the story of what transpired over a century ago. It is a significant piece of their community’s history.