Originally published on 11 February 2020 in the Pasadena Independent, Arcadia Weekly, and Monrovia Weekly

Very few of us realize that the Pasadena we know and live in today was built in the early 20th century by dreamers with grand visions who settled here from the Midwest and the East Coast. The Pasadena Museum of History (PMH) offers a compelling look at the most flourishing period in Pasadena’s history with an exhibition called ‘Starting Anew: Transforming Pasadena 1890 – 1930,’ on view until July 3, 2020.

I consider Pasadena my hometown and have lived here for 37 years. And while I dearly love my adopted city, I don’t know as much about it as I probably should. PMH’s exhibition provides that stimulating learning experience and Brad Macneil, Education Program Coordinator, who curated this show, happily gives me a tour.

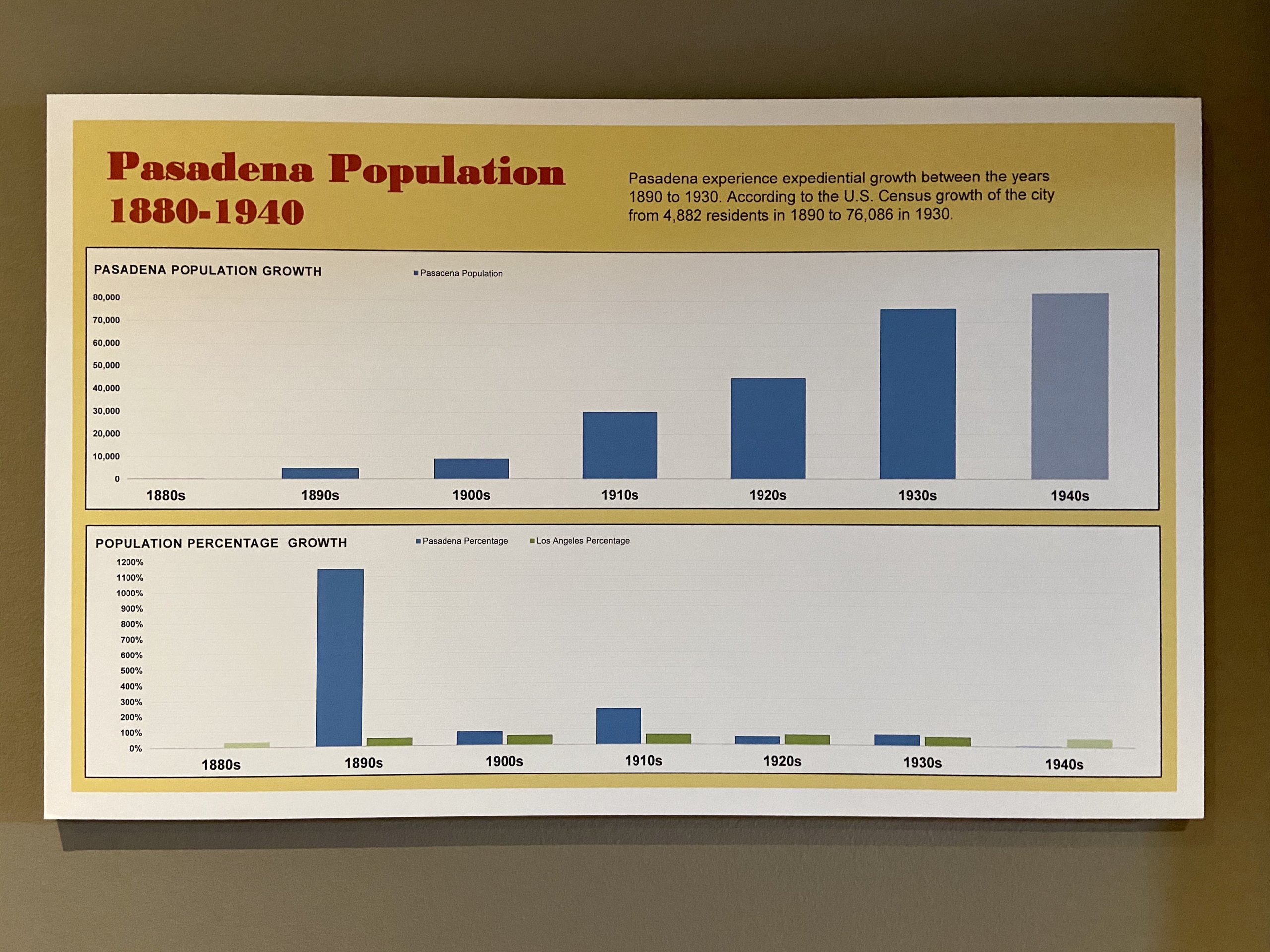

Our first stop is a chart which shows that population growth in Pasadena outpaced that of Los Angeles and then leveled off in 1930 when the depression hit. He discloses, “This was what sparked the idea for this exhibition. It was an amazing time in Pasadena’s history when the population went from below 5,000 to over 76,000 in just four decades. Today there are 150,000 – the population only doubled since. The city was transformed in so many different ways and our exhibit asks and answers a number of questions – why people came here, how they got here, where they lived, what they did, what kept them here.”

Macneil explains that the railway system started serving Pasadena in the mid-1880s, which caused the population to rise from 500 to 5,000 between 1880 and 1890. A photo of the Santa Fe Railway Depot and the Hotel Green greets us as we enter the first exhibition hall.

“Part of our exhibit tells the story of Dr. Adalbert and Eva Fenyes,” Macneil narrates. “The couple met in Cairo, Egypt and were married in Budapest. It was during their honeymoon around the world that they heard about Pasadena. They arrived at this train station in 1896 as newlyweds, and they had with them Leonora, Eva’s teen-age daughter from her first husband. They stayed at the Hotel Green for about three days and fell in love with Pasadena. They immediately leased a house on the Arroyo, which they later bought. Subsequently, they built two mansions here. One of the wonderful things about this exhibit is that we are able to display the museum’s collection. These are the Fenyeses luggage here and that telephone over there was inside the depot.”

“Besides word-of-mouth, a marketing campaign touting the city’s natural beauty and health benefits lured people to the area,” adds Macneil. “In the late 1880s big, fancy hotels were being constructed, the first of which was the Raymond Hotel. It was built by entrepreneur Walter Raymond, who had been working for a company back East that brought tourists here and thought Pasadena could use a grand hotel. Other hotels then were Hotel Green, the Pintoresca, the Maryland, the Huntington (which was originally the Wentworth and is now The Langham), and the Vista del Arroyo.

“Each year thousands came to Pasadena for the seasons – from November through March. The population would go up and down. The wealthy people came from the Midwest like Indiana and Chicago, and the Northeast – Boston, Philadelphia, and New York. Because of the winter resort business, the whole town grew. Visitors needed service, which opened up employment opportunities. That brought in working class people from other parts of the country to get jobs in the railways, hotels, and in agriculture. Professionals also arrived – doctors, lawyers, newspaper publishers. Pasadena grew into a diverse community – there was already a large Mexican American population, then the Armenians, the Chinese, and the Japanese arrived. They came to either find a job or start a business.”

Pasadena was a great place to be an entrepreneur and PMH’s exhibition highlights four enterprising people who came here with very little yet built successful establishments. One of them was Elmer Anderson who arrived with nothing more than a typewriter repair kit and founded Anderson Typewriters. Known today as Anderson Business Technology, it has branches all over Southern California selling business equipment and is still being run by his descendants. The local store on Colorado Boulevard, near Arroyo Parkway, remains to this day.

Many of us will recognize the edifice resembling a Chinese Imperial Palace on Los Robles and Union Street as USC Pacific Asia Museum. Back in the 1920s it was Grace Nicholson’s Treasure House of Oriental Art. She came here with a small inheritance and opened a curio shop selling Native American arts and crafts. She developed great relationships with Native Americans in the Southwest and eventually started selling to the finest museums in the country, including the Smithsonian and Field Museum. She later switched to Asian artifacts and created her treasure house where she lived and worked.

Adam Clark Vroman, an avid book collector and photographer, moved to Pasadena from Illinois hoping the climate would help his wife recover from her illness. Unfortunately, she died two years later. Brokenhearted, he sold his book collection to raise the capital to open Vroman’s Bookstore. As he had no direct heir, he made arrangements for his employees to take over the store when he passed away. It was a remarkable demonstration of how much he cherished and took care of his staff. Some of the descendants of those employees run Vroman’s today and it remains a beloved Pasadena purveyor of books and gift items.

There was Ernest Batchelder who came here to teach art at Throop Institute. He later started his own business – making the eponymous tiles – and became the foremost proponent of the American Arts and Crafts Movement.

Architects and builders prospered at this time because people needed housing. Those who came here for work built bungalows and cottages. Macneil states, “The cost to build a house varied from under $1,000 up to $100,000. Between 1902 and 1918 the median value of local houses was $1,700 (these houses today cost over a million dollars). Those with wealth seasoned in Pasadena and stayed for months at a time. A number of them decided to build winter homes on Orange Grove Boulevard, otherwise known as Millionaires’ Row. Displays of some of these grand houses include Adolphus Busch’s; the Gamble house, which still exists today; the Merritt House, which is now surrounded by million-dollar condos.”

After the depression, the owners of these mansions couldn’t afford the upkeep and sold them. Of the 52 mansions, only six or eight of them remain; the rest have been razed to the ground to make room for apartments and condominiums. Of course, even these divided-up homes are not for the middle- and working-class as they lease for several thousand dollars a month or sell for millions.

One of the mansions that’s still around is the gorgeous Marshall-Eagle Estate built in 1919 for $500,000 (valued at $8 million at the time) and is now Mayfield School. The exhibition has a display of it that tells its history and shows interiors shots.

Throughout the exhibit, PMH reveals the passage of time through changes in fashion and technology – dresses from the different decades; a high-wheeler bicycle; a carpet sweeper; an Edison machine; a record player; a gas-powered hair curler, one of the first dial telephones ever made, and an early typewriter. Macneil says students love to see and handle the typewriters but can’t figure out how to use the telephone.

Macneil leads me to the next display, saying, “Our story goes on about the Fenyeses becoming part of the community. Eva designs her first mansion, a Moroccan palace on Orange Grove Boulevard. This is Eva’s sketch of her mansion – there is an area that’s all glass, one of the first commissions of Walter Judson of Judson Stained Glass Studios. Her daughter Leonora grows in age, marries, and moves away. Eva gets immersed in the community business-wise by buying real estate and as a socialite by being involved with the art scene. Dr. Fenyes gets his medical practice going.

“Pasadena was one of the main art colonies in California during this period, so we have here a wall of art featuring selected works of the artists who lived here then. One of Eva’s biggest legacy was being patron of the arts and helping other artists in the community. She was a prolific painter herself and we have a lot of her art at the mansion, some of which we show here.”

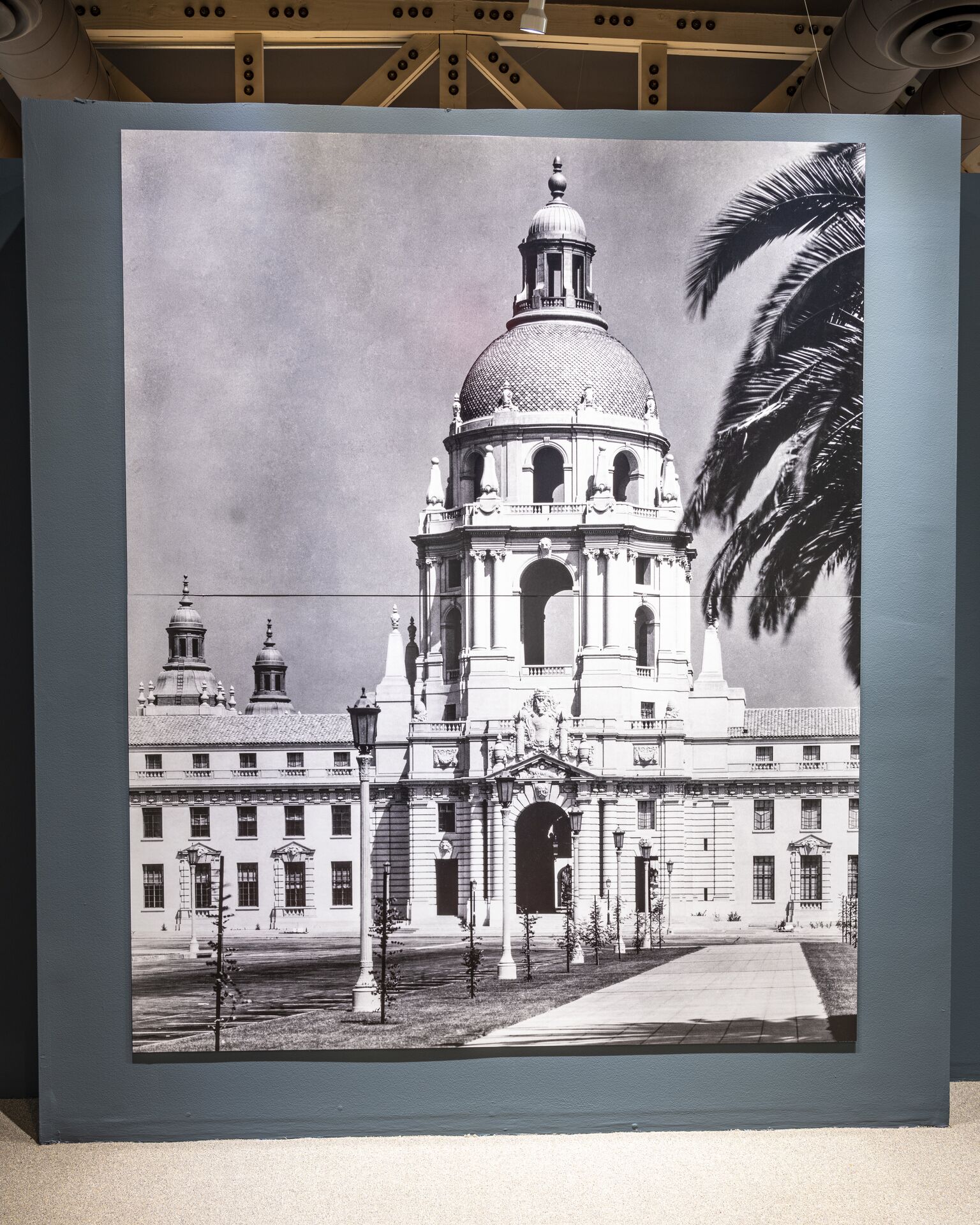

The second part of the exhibition, in the opposite hall, begins with an iconic image of City Hall and explores how the ‘City Beautiful Movement’ ushered the Golden Age of Pasadena. Macneil expounds, “In the Chicago Exposition of 1893, they built the White City. Many famous architects helped construct wonderful buildings, public plazas, and garden areas for the World Fair. The ‘City Beautiful Movement’ came out of that. The idea is that if you beautify the city with these magnificent public structures, it uplifts all the residents spiritually and morally.

“A lot of people from Pasadena were able to go the Chicago Exposition of 1893 and when they came back, this philosophy took off. They pulled people together, held meetings, and talked about what they could do. And the first thing they did was clean up the city. They got rid of the tacky real estate signs in the main part of town, tidied vacant lots, planted trees and flowers, painted buildings, and regulated architectural styles. It began in the early 1900s with input from various people in the city – movers and shakers as well as the general population. They came up with the plan for the city and things took off in the 1920s when money and the will were there. And so they erected grand public buildings. A main area was the Civic Center – City Hall, the Public Library, the Civic Auditorium. Most of what we identify with Pasadena today – the beautiful architecture, the cultural institutions – were built at this time.”

“There’s a section called ‘Nature versus Man-Made Beauty,’” Macneil goes on to say. “Out-of-towners came here because of the natural beauty of the area – like the Arroyo and the mountains. Then people created man-made parks bringing in trees from other parts of the world, changing the landscape. We have images of Central Park by Castle Green, Library Park by the Senior Center, and Brookside Park. There’s Eva’s picnic basket because she enjoys going on picnics.”

Macneil points to the next section, “Here we talk about the various means of transportation. During this period of time, people got around town by walking. But there were also buggies and carts, trolley cars, and automobiles. But bicycles were the biggest thing – there were more bicycles per capita in Pasadena than any other city in the United States. This is an early-1900 map of the bike trails and roads in California.

“Because of the power of the bicyclists as a group, they put a lot of pressure to make the streets and signage better, even before they were done for cars. This is California Cycleway, an elevated tollway for bicycle traffic which ran from the Green Hotel to South Pasadena. It was planned to go all the way to Los Angeles but it was never completed because Horace Stubbins encountered legal battles with Henry Huntington over right-of-way. He decided not to pursue it, but the family did keep some of the right-of-way and was able to sell it to the state for the Pasadena freeway. This is still a dream of some people to build – imagine how wonderful it would be to ride your bicycle high above the streets on a road that ran along the Pasadena freeway.

The ‘Kids Corner’ has a display of things kids wore, what types of games they played, where they went to school. There are hands-on items like the stereoscope that kids can look through and see three-dimensional images.

A section that Macneil calls ‘The Extraordinary Excursions’ features three early theme parks, the first of which is Busch Gardens. According to Macneil, Adolphus and Lilly Busch, of the Anheuser Busch and Budweiser fame, had a house on Millionaires’ Row. Adolphus bought approximately 37 acres, covering the area from his house on Orange Grove to the Arroyo, on which he created this magical park and opened it to the public for free. However, the park subsequently met the same fate as that of the grand estates in the area – it closed in the 1930s and 1940s and was subdivided. Lilly tried to make an arrangement for the city to take it over but it was too expensive for the city to maintain.

Another was the Cawston Ostrich Farm. Macneil relates that entrepreneur Edwin Cawston, who had learned about ostriches and the ostrich feathers trade in South Africa, came in the late 1880s to open a business here. He had stores in New York, San Francisco, and Los Angeles selling feathers all over the world but it was in South Pasadena that he established one of the first ostrich farms in the country. At the same time, he created a beautiful park-like area where people could come and observe the ostriches’ little chicks, see the big birds being fed, and watch ostrich races. They could even ride on a cart behind the ostrich and, if they were brave, on the ostrich. It became quite a popular destination.

Around the corner you’ll come upon photographs of the Mount Lowe Railway, a series of scenic railroads which went up the mountains above Altadena, created by Thaddeus Lowe. Visitors taking the train up reached a beautiful destination with four hotels, a zoo, an observatory for star-gazing, and a golf course. Macneil says, “People would take the Pacific Railway from all over Southern California, but especially from Los Angeles, come into Pasadena and up to the foothills of Altadena. They’d get off the trolley car and on what they called the ‘white chariots’ that would take them on a steep incline. They would come up to the first hotel and alight there. Then they would get on a trolley car that wound around the mountains until they arrived at the topmost hotel – the Alpine Tavern.”

People got their entertainment during that period from the Pasadena Playhouse and cinemas which started out showing silent movies. “Then there was the Grand Opera House, which was located close to Green Hotel,” recounts Macneil. “It was built by entrepreneurs who brought great opera to town while simultaneously hoping it would help raise real estate values. However, it failed to take off partly because it competed with an opera house in Los Angeles which got the better acts.”

Macneil adds, “When I did my research, I used the city directories going back to the 1880s and found pages upon pages of clubs, associations, and societies where everybody belonged. People came together through their common interests – whether it was just for fun or for a civic purpose.

“We showcase three of these organizations: the Valley Hunt Club for men and women, started out in 1890 as a hunt club, as the name implies. It then became more of a social club and gave us the Tournament of Roses Rose Parade and Rose Bowl game. The Elks Club was a place for men to get together both socially and as a charitable group. The Shakespeare Club began as a women’s literary club to promote reading. All these three organizations were very involved with the community then and still are to this day. All these clubs, at one time or another, had entries in the Rose Parade and on display are trophies they had won. Some items are artifacts from the clubs.”

Towards the end of the exhibit, the display talks about the Fenyeses selling their big Moroccan palace and downsizing to the mansion in 1906. This section explores the life of Eva and Dr. Fenyes from 1906 to 1930. While they were world travelers, Pasadena was their home base. They were involved in the community in different ways – she was still a socialite; he continued with his medical practice and, being an entomologist, his work with beetles. Leonora, Eva’s daughter, became widowed and came back to live with them. In 1911, Eva, Leonora, and Leonora II all lived here and created a wonderful bond of three generations.

A wall of displays delves into the transformation of Pasadena. Macneil expounds, “Through the 1893 ‘City Beautiful Movement,’ city officials were able to hire architects from Chicago and established the Bennett Plan that created the Civic Center – the City Hall, the Library, and the Civic Auditorium. At the same time, more beautiful buildings were being erected and various infrastructure were being constructed. The Colorado Street Bridge was built in 1913 for people arriving by car to have a grand entrance into Pasadena. They also had plans for a beautiful art museum and school on Carmelita where the Norton Simon is now, although that never came to fruition.”

The 1920s were the Golden Age of Pasadena when innumerable buildings featuring European architecture were constructed all over the city. Schools and city service structures were being upgraded; the Rose Bowl was built. PMH’s exhibit has a video that shows the changing cityscape.

“And then the depression hit and everything slowed down,” says Macneil. “The Civic Auditorium hadn’t been completely built. Fortunately, city officials were able to do some creative financing to finish it but several things which were on the planning stage stopped. The resort industry collapsed – hotels were torn down and were reused for other functions. The Vista del Arroyo, for instance, became a hospital; today it is the Court of Appeals. Of the hotels built during that period, only the Huntington Hotel still stands today. Population growth halted as well.

“At the very end of the exhibit, we showcase PMH’s mission – capturing and gathering the history of Pasadena and the surrounding area and sharing it with the public. Our collection encompasses this productive and transformative period so our archives and collection department were quickly able to put together what we felt would represent that time.

On the Curator’s statement, Macneil confesses that while he was born and raised in the area – three generations of his family lived here – he didn’t fully appreciate Pasadena. It wasn’t until he went away for a while and then returned that he developed his deep love for the city. Through this exhibit, he hopes that he can share all that he has rediscovered

Macneil states, “We’re hoping parents come with their children to our exhibition. We’re purposefully keeping it open until July 3rd so students from both public and private schools can learn Pasadena’s history. How fun would it be for these young people to learn what happened a century before their time and then see the structures when they walk around the city.”

As PMH has detailed in the exhibition, some of the dreams of the city’s visionaries worked and some didn’t. But many of the magnificent and architecturally diverse structures from the city’s Golden Age remain and they are what give Pasadena the culture and history for which it is renowned. And through this exhibition, Macneil wants to remind people what we are capable of doing if we pull together as a community. The past can be used as a blueprint for the future.