Also published on 20 October 2025 on Hey SoCal

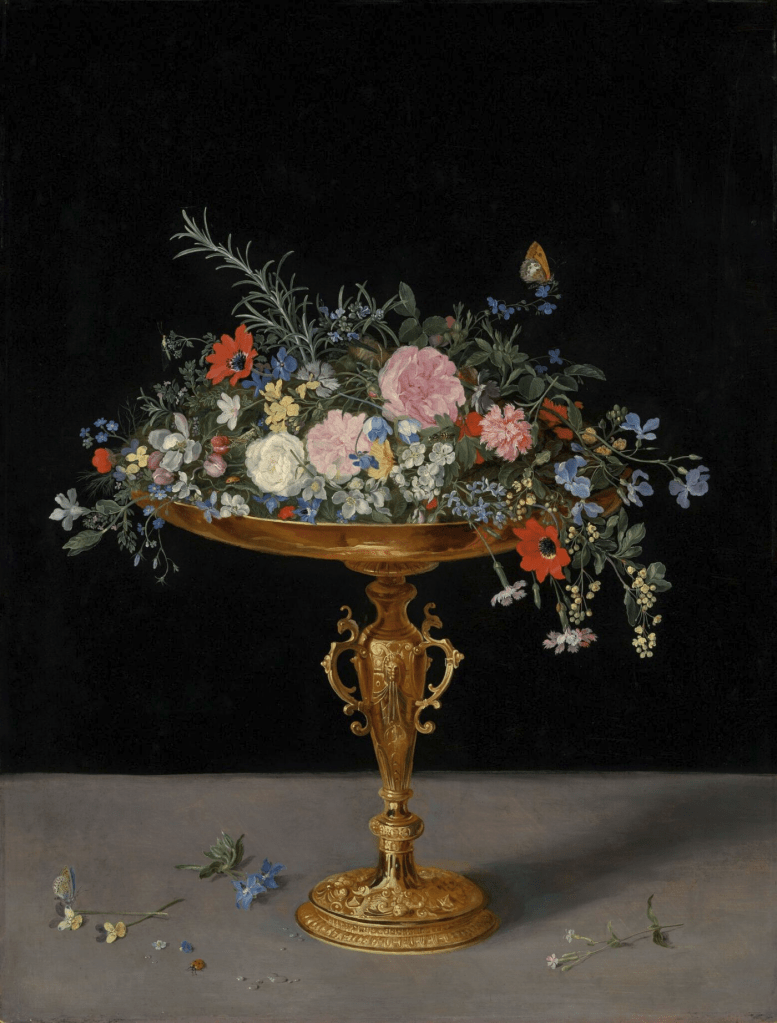

Jan Brueghel the Younger. Flowers in a Gilt Tazza, c. 1620. | Photo courtesy of The Norton Simon Foundation

October 24, 2025 marks the 50th anniversary when the Pasadena Art Museum was renamed Norton Simon Museum. It is only fitting then that 50 years to the day, the museum will debut the exhibition called “Gold: Enduring Power, Sacred Craft.” On view in the lower level exhibition wing through February 16, 2026, it explores the artistic and cultural function of gold in 57 objects drawn from the museum’s American and European and South and Southeast Asian collections.

The objects in this exhibition were crafted from metal excavated from mines across three continents and transported over vast regions, often in the form of currency. In the hands of trained craftspeople, this processed gold was transformed into jewelry that adorned Roman patrician women or spun into thread that was then woven into textiles for elite patrons in Europe and Asia.

Co-curated by Maggie Bell, Norton Simon Museum’s associate curator, and Lakshika Senarath Gamage, assistant curator, “Gold: Enduring Power, Sacred Craft” being the exhibition during the 50th anniversary celebration came about serendipitously. They had been contemplating to collaborate on an exhibition that would bring the Asian collection and the American and European collection together. When they began this project two years ago, they realized there was a common element in the artwork they were looking at.

“As we were looking at the objects in our collections, a theme emerged and we realized we talk about gold across mediums – tapestries, sculptures, painting, works on paper – as an opportunity to get to know and celebrate the collection,” Bell begins. “We systematically went through all the objects that had gold as a medium. At the same time we started thinking about the way gold as a metal interacted with other medium and also what gold means symbolically, even to representations of gold in thread or in paint. There are so many ways to approach this subject. There are things in the exhibition which don’t actually have gold in them but evoke ideas and associations with gold.”

Later in the process they realized the exhibition they had been planning was going to be completed around the same time as the museum’s 50th anniversary celebration. And it was a happy coincidence because the milestone is traditionally symbolized by gold.

“With the story we wanted to tell together, we started with about 200 possible objects,” continues Bell. “We got to know these objects and started doing research. And one of the best things that happened in the process is that I learned so much from Lakshika about her collection and the stories and themes that we can tell together. In conversation with each other and through research we narrowed them down. There were only a certain number of objects that would tell that story clearly and we consolidated them to the 57 that visitors will see in the exhibition.”

“We want to explore gold as a medium but also as an idea,” Bell states. “We want to show the ways in which gold as a material physically does endure for millennia, hence the title. Also, it has a grasp on our imagination globally; visitors will see in the geographical range of these objects that gold really has so much power as a medium.”

The exhibition is divided into three themes: power, devotion, and adornment. The 57 objects represent about 17 countries across four continents, spanning from 1000 BCE to the 20th century.

“Through these works we explore how gold traveled across land and sea, how it was crafted, and how it has been imbued with special meaning, particularly with devotion,” explains Gamage. “This is possibly the first time South and Southeast Asian art are displayed together with American and European collection in the special exhibitions galleries. I do want to emphasize that this is not a comprehensive picture of gold because we are drawing solely from the Norton Simon Museum collection and these objects were mostly sourced by Norton Simon himself.”

Museumgoers will find a clean, front-facing plan and objects displayed on tables in the center instead of against the wall. The first gallery focuses on power, the second on devotion, and the third contains jewelry and the smallest objects. Interior walls and display stands are painted red, inspired by a lot of the images in the space. The lighting will be different in each gallery.

Gamage elaborates, “Visitors won’t see any artwork on the peripheral walls and it’s a deliberate design choice to give prominence to the objects. Maggie and I worked very closely with the designers to create an exhibition that felt meaningful to visitors. The layout allows them to create their own pathways and gives them the freedom as they walk around to see these connections with their own eyes. And rather than separating them into just Asian and European, we wanted the objects to have interesting sightlines so visitors can see Asian objects visually interacting with American and European objects. That highlights function and meaning, whereas a division by geography and time loses those meaningful trajectories.”

A map at the entrance indicates where the objects originated and where the gold came from. In the first gallery, the very first object visitors will see is a bovine sculpture from 18th century China.

“We chose this because it is associated with strength, power, and resilience, and possibly tied to ancient Chinese feng shui tradition,” explains Gamage. “The function is not exactly known because not much research has been done about this object. The practice itself remains unclear but the charging bull has long been viewed as an auspicious symbol of prosperity and abundance.”

One of the foremost European objects in the first gallery that addresses the power of gold – both as an economic material as well as a symbolic medium – is a portrait of Sir Bryan Tuke, who was appointed treasurer and secretary of Henry VIII’s royal household in 1528.

“This is a copy after a painting by Hans Holbein the Younger, a German artist primarily for the court of Henry VIII,” Bell describes. “Holbein was both a painter and a jeweler and was renowned for designing jewelry for Henry VIII and his wives, and incorporating those designs into the portraits he did of the people in Henry VIII’s court. Because Holbein was a 16th century artist and this was done in the 17th century, it’s possible that Tuke’s descendants commissioned the new portrait to hang in their home as a reminder of their own connections to the Court of Henry VIII in the previous century.”

“It’s very true to the original Holbein portrait especially in the way that the cross jewelry is hanging around Bryan Tuke’s shoulders,” explains Bell. “It’s very conceivable that Tuke designed this hefty gold cross himself. I really like this image because a treasurer gets the economic power of gold; it also has an interesting symbolism around the use of gold in this portrait. When this was painted Tuke had just recovered from a really serious illness. It has additional meaning because gold was associated with longevity and good health since it never tarnished.”

In the second gallery, objects on devotion and the sacred role of gold in making art are displayed.

“It was a really fascinating theme to think through with Lakshika because gold has different meanings in Christianity, Buddhism, and Hinduism that is very complex,” Bell declares. “For example, in the Christian tradition, gold is incorporated into images of religious figures as a way to honor them. But it also becomes a bit tricky because poverty is such an ideal in Christianity, so integrating gold undermines the value of poverty as a Christian virtue.

“But in Buddhism, there is the tradition of genuine sacrifice that comes from giving gold as a gift. It was really interesting to think through those ideas with Lakshika in terms of using gold to craft religious images and the different symbolic and devotional implications that they have.”

One of the first European displays in the second gallery is a painting called “The Adoration of the Magi.” It is a scene showing the three kings who traveled from the four known corners of the world – Asia, Europe, and Africa – to honor the Son of God with extravagant gifts of frankincense, myrrh, and gold..

“What I found interesting that I didn’t realize, is that in a lot of these images from the 16th and 17th century, Christ is shown interacting with this pot of gold,” says Bell. “I find that thought-provoking because, at the same time. the Holy Family was also honored for their poverty. Christ was born in a manger, surrounded by farm animals but he was being honored with gold and he’s reaching out for the gold, and in some paintings even holding the gold coin.”

A South Asian object in the second gallery is the sculpture of Indra – the Hindu god of storms, thunder, and lightning, and was historically the king of gods.

Gamage states, “Indra is in this particular posture called the ‘Royal Ease.’ He wears a very distinctive Nepalese crown and he also has a horizontal third eye that clearly tells us that this is the god Indra. There are various ceremonies that are very specific to the veneration of Indra, particularly in the Kathmandu Valley in Nepal.”

In the third gallery, called adornment, objects are mostly jewelry. The one object from the Asian collection is a bracelet made of pure gold dated 1000 BCE – the oldest object in the exhibition. It is from the Uragu Kingdom, which is modern Turkey, Armenia, and part of Iraq.

“We have an eclectic group of ancient European objects,” enthuses Bell. “There are two Egyptian cats that we’re really excited about. These were on trend for collectors in the 1960s. We have figurines of various goddesses decorated in gold in someone’s home as talismans. We have this fantastic pair of earrings which are hollow inside but made of pure gold. They’re beautiful! It’s a testament to the power of gold – it doesn’t tarnish even after millennia. We were desperately trying to find photos of Jennifer Jones, Norton Simon’s second wife, wearing these to some events. But we have not been able to verify this.”

The Gold exhibition will feature four technical stations, created by the museum’s conservator, behind the two large tapestries. Bell expounds on the reason for this.

“We’re thinking about gold as a material and we had no idea about the many ways gold can be manipulated to become ink, paint, thread, leaf, or something you can melt. There are so many things you can do with gold. It’s alchemical in a real sense. We kind of condensed them into these four major techniques that you see throughout the show: gold leaf on painted wood panel, gold threads, gold paint, and gilded cast metal – which is the majority of the work that Lakshika is displaying from the South and Southeast Asian collection. So we’re very grateful to our conservator and we hope they will enhance the exhibition experience for our visitors.”

Asked if they learned something when they worked on the exhibition they didn’t know before, Bell replies, “Training our eyes to recognize the different techniques was a skill I didn’t have before. That was something we acquired through looking at objects to get a sense of ways that gold paint or gold leaf could be applied. And also, just understanding the complexity of gold as the material resource in the world. What’s it meant to get from a mine or a river into the hands of the artist is extraordinarily difficult to understand, and I was very humbled by that research.”

Gamage echoes Bell’s sentiment “One of the most interesting things I learned is a very deep appreciation for those artists who used gold in magical ways we would never even have imagined. For example, to see how gold was coiled and wrapped around another thread and how it was used in a tapestry, cut silk embroidery; or in painting as gold leaf. Today, we have this state-of-the-art technology and are capable of so many modern and technological marvels. But to know that humans were capable of such intricate and extraordinary artistry was deeply humbling, to mimic Maggie’s words. That level of technical expertise and finesse they had – and that they did by hand – is something that still amazes me.”

The Norton Simon Museum’s 50th anniversary celebration will include a community weekend, which is free to the public, to be held on November 7, 8, and 9. There will be exhibitions, various activities, live music, and the unveiling of the improvement project.

A book called “Recollections: Stories from the Norton Simon Museum” is also available for purchase. A fascinating read, it contains essays penned by former and current staff about some of the paintings, sculptures, and artworks in the museum’s holdings.

In the book’s introduction, Emily Talbot, Vice President of Collections and Chief Curator, recalls the museum’s history. Maggie Bell traces Tiepolo’s “Allegory of Virtue and Nobility’s” acquisition and journey to Pasadena. Talbot lets us in on the little-known friendship between Norton Simon and abstract expressionist artist Helen Frankenthaler. Dana Reeb’s essay informs us Simon amassed one of the largest and most important Goya print collections in the world. Likewise, Lakshika Senarath Gamage reveals how Simon assembled the largest body of Chola period bronzes that allowed him to wield the most influence in this area of the art market.

Rachel Daphne Weiss explores the collaborative purchase of Poussin’s “The Holy Family with the Infant St. John the Baptist and St. Elizabeth” between Simon and the Getty. Leslie Denk writes about Cary Grant’s gift to the museum of Diego Rivera’s painting “The Flower Vendor.” Gloria Williams Sander gives us an insider look at how the right frames present paintings to their best effect. Bell’s second essay sheds light on how the West Coast exhibition “Radical P.A.S.T.: Contemporary Art and Music in Pasadena, 1960-1974” explored Pasadena’s role as a generative hotbed of contemporary art. John Griswold, Head of Conservation and Installation, discusses the museum’s collaborative approach to conservation.

Gloria Williams Sander reflects on the moment Photography became accepted in the art world as a medium worthy of collecting and exhibiting. Alexandra Kaczenski uncovers the legacy of Printmaking in Los Angeles. Gamage’s second essay examines Architect Frank Gehry and Los Angeles County Museum of Art Curator Pratapaditya Pal’s vision for the Asian galleries and the arrangement of the objects displayed within. The last essay by Griswold and Talbot talks about the Norton Simon Museum’s loan exchange program, which gives museumgoers the opportunity to view significant artworks from the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC, the Art Institute of Chicago, and the Musée d’Orsay.

Norton Simon’s extraordinary art collection has been a Pasadena treasure since its founding. It has magnificently lived up to the purpose Simon envisioned when he assembled one of the finest European and South and Southeast Asian masterpieces in the world. In the capable hands of the museum’s stewards and curators, Simon’s legacy will continue to enrich our lives and flourish well into the next 50 years.