Originally published on 15 October 2019 in the Pasadena Independent, Arcadia Weekly, and Monrovia Weekly

The year 1919 was significant for so many reasons but none would affect the art scene and cultural life of the San Gabriel Valley more than the founding of the Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens. And we have Henry and Arabella Huntington to thank for bestowing on us their incomparable legacy.

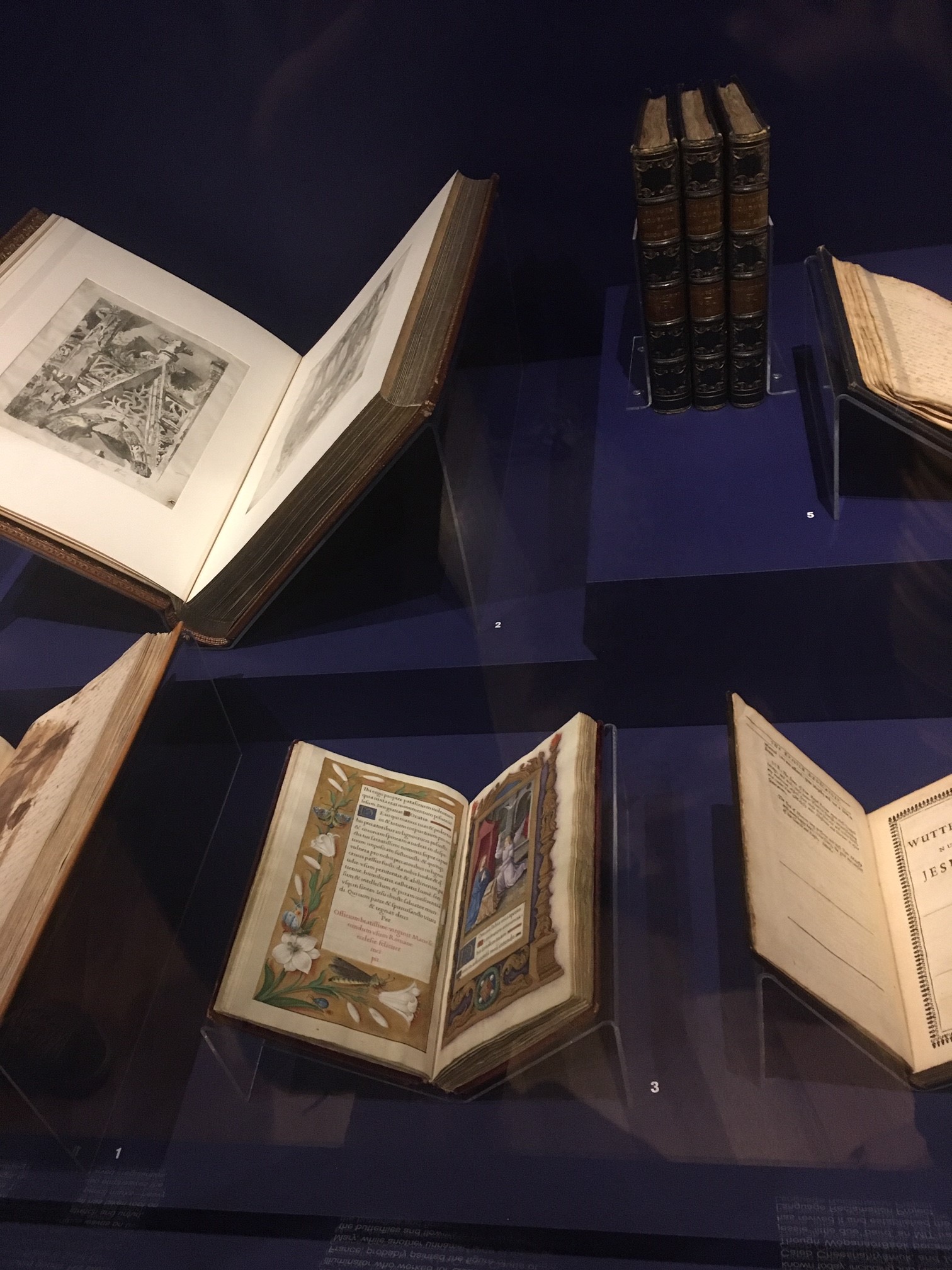

An exhibition called ‘Nineteen Nineteen,’ which opened September 21 and will be on view through January 20, 2020, at the MaryLou and George Boone Gallery showcases 275 items from Henry and Arabella Huntington’s vast collections, some of which have never been displayed.

Co-curators James Glisson, interim chief curator of American art, and Jennifer Watts, curator of photography and visual culture, led a team from the three divisions and went through the institutions massive storehouse of 11 million items. The objects in the exhibition range from posters from the German Revolution, abstract art, suffragist magazines, children’s books, aeronautic manuals, self-help guides for soldiers returning home from World War I, and a book hand-printed by Virginia Woolf at her kitchen table. The thread that ties them all together is that they were all acquired in 1919.

During a preview of ‘Nineteen Nineteen,’ Glisson and Watts walk members of the press around the Boone Gallery to show the items, explain their significance, share their experience, and add their personal insights.

“This project took about two and half years from the very beginning to the end,” begins Glisson. “I went through, probably, 3,000 items, but it could have been more. And a lot of time was spent finding things from 1919 that were interesting, because there were a lot of stuff that weren’t,” he adds with a laugh.

“Or visually compelling,” inserts Watts. “Gathering these things was incredibly labor intensive but fun at the same time. I have to point out, though, that we had research assistants, interns, and grant assistants who did a lot of work – it was a collective endeavor. It involved every curatorial staff across all divisions – the library, the art museum, and the botanical gardens. We knew some things to look for and others were hunches. We asked our colleagues for assistance and they came to bat. They helped us find things we never would have unearthed on our own.”

Glisson expounds, “Often, it was ‘There’s this great thing, I think it’s from 1919;’ ‘Oh yes, it is.’ This is where the process was different. We knew where we wanted to take it but until we gathered the material together, we couldn’t tell a story. We didn’t know what the story was before we had the material. The verbs came when this checklist was two-thirds through – and we knew what the themes would be and gave it some shape. As Jennifer said before, we had to just be incredibly open to where the material was taking us. It’s like, we see a piece and we say ‘What does this mean?’ Or, sometimes, it’s ‘This is interesting, what is it?’”

“I like to take the analogy of when you look at a centennial and think of the founders, and you put them at the top of your pyramid,” explains Watts. “We decided to invert the pyramid, and put the context and the year at the top. Most of the time, when you’re doing an exhibition, people come up with an idea and they look for the material to support it. We flipped it and said ‘Let’s look at the material and figure out what the bigger ideas and themes are.’”

The exhibition that Glisson and Watts created from that starting point, which Glisson describes as ‘From the global to the local’ is organized around five broad themes – Fight, Return, Map, Move, and Build.

Glisson elucidates, “We wanted to harness the large number of 1919-related items here into something provocative, allowing the visitor to interpret the period in a fluid way. Rather than telling a neat, resolved story, we tried to capture the jarring experience of life during a year that everyone understood was an inflection point for world history. Empires had fallen in the Middle East and Eastern Europe. Millions had died fighting and in a flu pandemic. Delegates at the Paris Peace Conference tried to sew a tattered world back together. Like today, people felt that irrevocable change was underway. The issues of 2019 – immigrant detention, women’s rights, and the fight for a living – were equally pressing in 1919.”

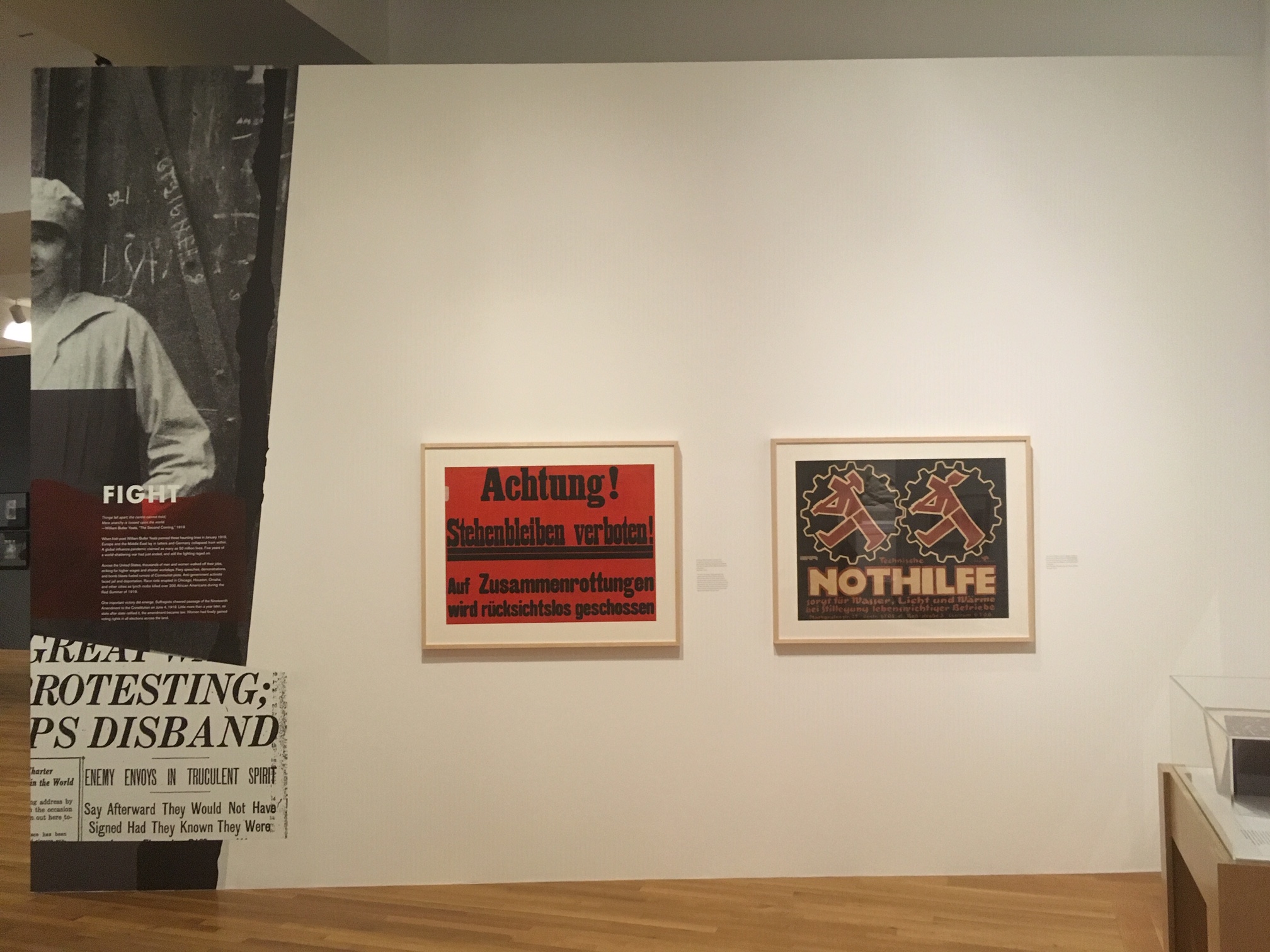

As detailed in a news release from The Huntington’s Communications Office, the ‘Fight’ section of the exhibit shows that, while the war might have officially ended in 1918, other battles raged on in Los Angeles, the rest of the nation, and Europe. A global influenza pandemic killed millions of people, claiming three percent of the world’s population. Laborers agitated for better pay and safe conditions. Rumors about a Bolshevik plot to upend the U.S. government led to a Red Scare. Violence erupted in a season described as ‘Red Summer’ for its deadly riots and lynchings of African Americans. In 1919, the bill that would clinch American women’s right to vote passed in the Senate, and temperance advocates won their fight for prohibition. Modern artists and writers responded to the tremors of the age, including the carnage of world war, by breaking with convention and tradition.

Items in this section include: German posters related to social and political upheaval; original photographs and materials documenting the flu pandemic here in Pasadena; national strikes and labor unrest; U.S. Marshal records (including mug shots and probation letters from German citizens jailed in Los Angeles during the war); and objects that tell the story of the fight to ratify the 19th amendment.

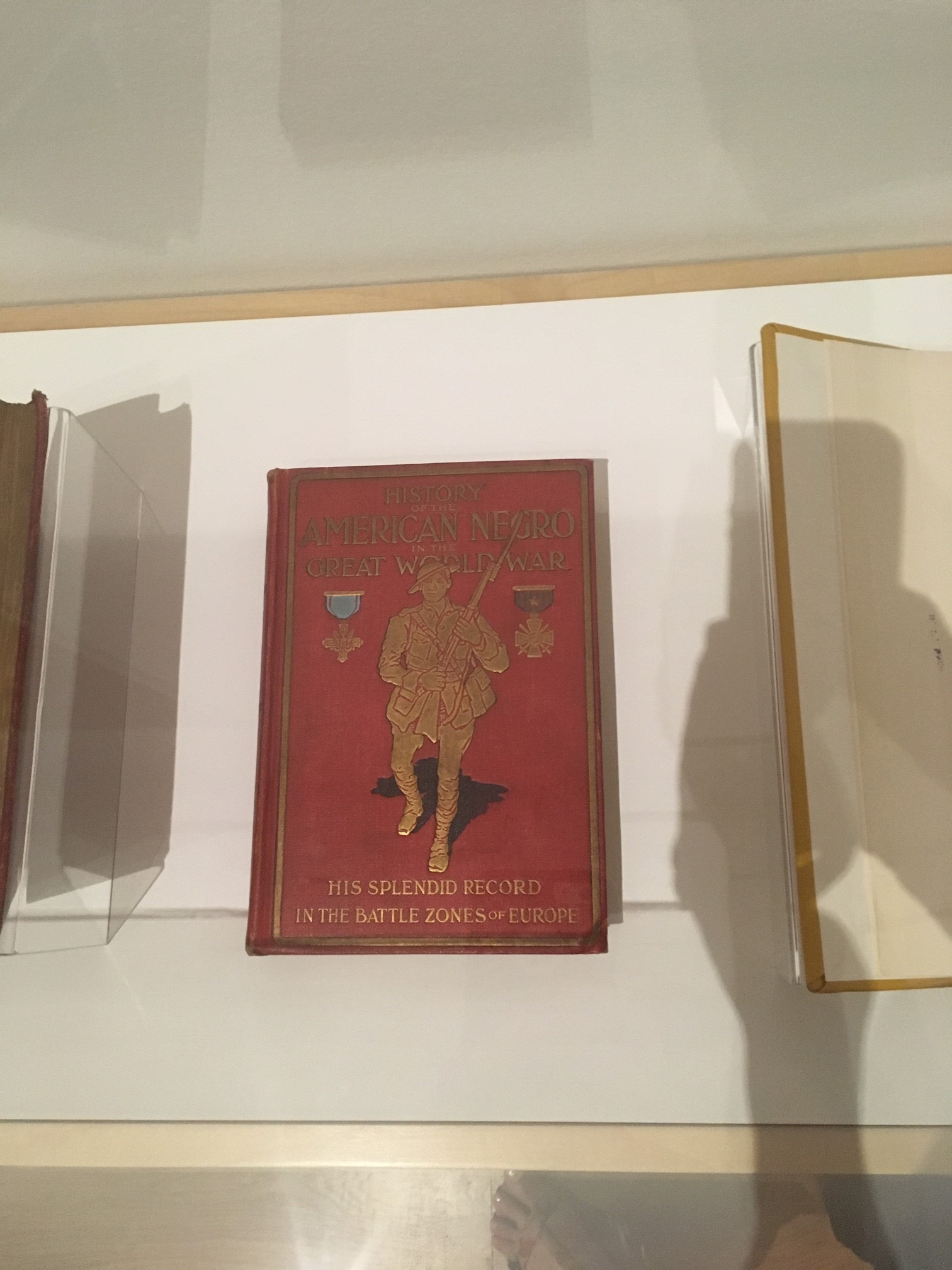

The ‘Return’ portion focuses on the immediate aftermath of the Great War, when millions of men and women – including 200,000 African America soldiers – headed for home. Survivors sought to understand and memorialize the war’s events through personal reminiscence and published accounts. Artists, some of whom served overseas, interpreted what they had seen, while others found inspiration in canonical tradition and myth. Popular music and illustrated books also offered safe harbor in tumultuous times.

Materials from this segment comprise: Liberty Loan posters; soldiers’ recollections; a rare Edward Weston portrait of dancer Ruth St. Denis; Cyrus Baldridge’s illustration ‘Study of a Soldier;’ and John Singer Sargent’s ‘Sphinx and Chimaera,’ which depicts a mythological scene.

In January 1919, President Woodrow Wilson and Allied heads of state gathered at the Paris Peace Conference to make new maps of a changed world. The carving up of ancient empires created new nations in the Middle East, Eastern Europe, and Africa, while regional promoters published maps to highlight Southern California’s capacity for growth. High above Los Angeles – at the Mount Wilson Observatory – the world’s largest telescope was on a nightly quest to chart the universe. In a world turned upside down, maps offered a welcome measure of predictability.

What the charting of territory that occurred that year meant and its resulting significance are explored in the ‘Maps’ section. On view is a first edition of ‘Traite de Paix,’ the Treaty of Peace signed at Versailles on June 29,1919, with a map showing new territorial configurations; an album of autograph signatures gathered at the Paris Peace Conference by T.E. Lawrence, otherwise known as Lawrence of Arabia; rare maps depicting population, transportation, and demographic data in Los Angeles and the nation at the time; and original astronomical photographs of the moon and constellations.

While working on this project, Glisson and Watts found out that Huntington was obsessed with maps. She says, “If you think about it, it’s not that surprising given that he was probably one of the most influential people in setting the course of how our sprawling city came to be. We discovered the spectacular 39-foot long Pacific Electric linen map that shows the real estate holdings contiguous to the line which is part of Huntington’s development scheme. People may not realize that while the Pacific Electric was a component of the world’s largest transportation network at the time, it really was a loss leader for Huntington. He was most interested in getting people to the communities that he’d developed – Huntington Beach, San Marino, Glendale.

“This is a one-of-a-kind map and has never before been exhibited. It is an incredible document – you could see the level of detail on it. Every redaction, every addition is recorded by him. It would have been something that the engineers – and Huntington with them, because he was very detail-oriented – would be poring over. I like to call this the papyri of transportation. It basically shows the Pasadena short line, which was one of the first lines that Huntington put in to the Pacific Electric system and it goes from Old Town Pasadena all the way to the edge of downtown Los Angeles.”

This Pacific Electric map display also falls under the ‘Move’ portion of this exhibition, which examines the ways 20th century technologies – planes, trains, and automobiles – propelled a society on the go. Henry Huntington’s network of streetcar lines brought Angelenos from ‘the mountains to the sea’ and to far-flung deserts and farms. A burgeoning national road system made automobile travel possible and pleasurable as never before.

Also taking the spotlight in this section is the interstate automobile adventure of five friends, including famed aviator Orville Wright, assembled in a rare photographically illustrated volume titled ‘Sage Brush and Sequoia;’ works by T.S. Eliot and Virginia Woolf, published by Virginia and Leonard Woolf’s Hogarth Press.

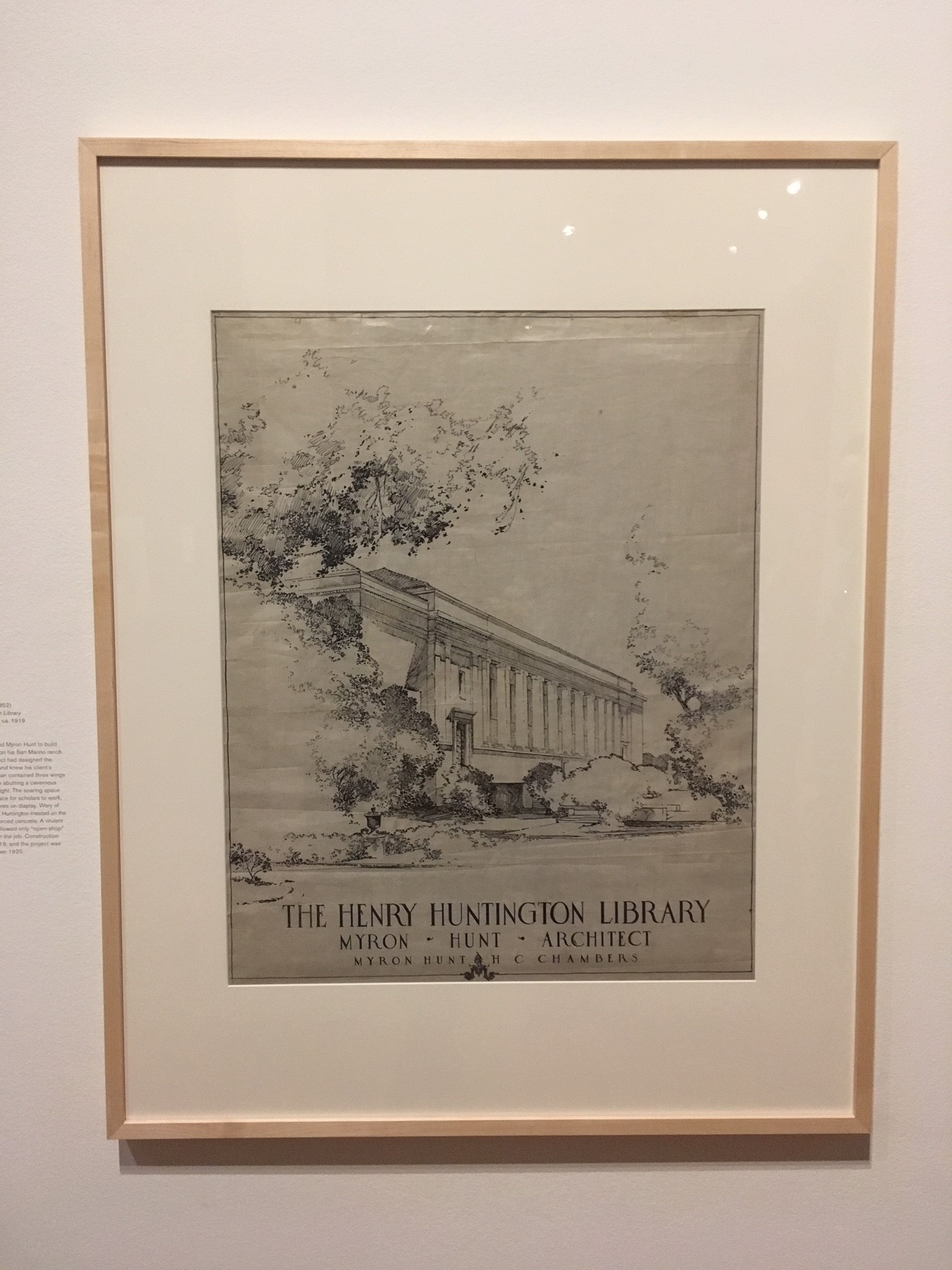

The last portion of the exhibition, ‘Build,’ focuses on Henry E. Huntington and the institution he created. In 1919, Huntington announced what some, including his New York librarians, had begun to suspect. He planned to load boxcars with the ‘world’s greatest private library’ – some 120,000 volumes – and send it off to the country’s western shores. By then, the property’s palm, desert, rose, and Japanese gardens were planted under the guidance of William Hertrich, Huntington’s landscaper. The mansion, designed by Myron Hunt, was completed in 1910. With the construction of the library building, the keystone fell into place for what would become the beloved tripartite institution we know today.

A George Washington Wall – an installation of paintings – is also part of the exhibition. “This little section is an homage to Huntington’s own collecting and what he was doing in 1919,” Watts elucidates. “In 1919, he purchased four stunning portraits of George Washington, including the most famous one by Gilbert Stuart. Why was be buying portraits of George Washington in 1919? Firstly, it was the trend. There were a lot of things coming on the market then and George Washington was the most iconic figure at that stage of America. And, perhaps, because Huntington did this audacious thing of locating this giant institution and collection on the West Coast, for which he took a lot of criticism that he was taking what was considered the cultural patrimony of America and Europe and exporting it to this cultural wasteland of Los Angeles. I think Huntington wanted to ensure this institution took its rightful place in the cultural landscape and who better to do that than George Washington, the first in the hearts of his countrymen? And, of course, it also demonstrates Huntington’s admiration for first founders.”

In December of 1919, Huntington invited members of the prestigious New York Authors Club to his Fifth Avenue home. At that exclusive event, he shared with them 35 treasures in which he took special pride.

Watts declares, “This was significant for a couple of reasons – we had very little understanding of what he liked or favored. We know what his collecting interests were but we don’t know what his personal favorites were because he didn’t write or talk about them. This group of objects gives us a little insight as well as showcases his overarching collecting interest. Out of these 35 items, we chose some things that we thought were really outstanding and not generally on exhibition. They include: Benjamin Franklin’s handwritten autobiography; Maj. John Andre’s Revolutionary War-era maps; the first Bible printed in North America in a native language, which is also called the Eliot Indian Bible after the Englishman who translated it; and Civil War General William Tecumseh Sherman’s four-part memoir never before examined by scholars. The pages open to the redaction pertaining to his mental illness which ran in his family.”

Rounding up the exhibition are displays related to the make-up of this institution. Says Watts, “One of the things I like to tell people is that in 1907, at the beginning of Huntington’s collecting career, there was a big article in the New York Times about the most important collectors in the country and Huntington appeared nowhere. In 1919, when this institution opened, he was called one of the world’s greatest collectors, having one of the world’s best private libraries. How did Huntington do that? He was a consolidator and amalgamator – he bought huge libraries all at once. He had purchased four of the libraries that were mentioned in the 1907 article. We included several book bills to show the range of people he was dealing with and also the kinds of things he was buying. A favorite of mine is the one from Rosenbach, who was one of his major dealers. He delivered $121,000 worth of Shakespeare’s works to the San Marino estate. That gives you a sense that he purchased aggressively.”

“Among the many surprising things we learned, we determined that in the early years he was planning on importing all sorts of seeds and plants not as a collector but to landscape his real estate holdings,” Glisson discloses. “He was trying to figure out what would work here and it evolved into a teaching collection, something akin to what Harvard was doing in his botanic garden. The other thing that was really fascinating was that in the beginning he thought he could finance this whole enterprise entirely on citrus. Through all sorts of formulation of various fertilizer and types of trees, Hertrich was able to tell Huntington which are the best varieties and how much they’re making. Unfortunately, citrus isn’t the most reliable revenue source and, on top of that, 1919 was a bad year for citrus. Huntington ultimately had to sell some properties to finance this place. In 1919, Huntington had 600 acres; today his estate has 207 acres.”

Watts leads us to a small section, explaining, “This is a kind of homage to Hertrich. Here we see some of the early photographs of the property that he took and his little notebook with a listing of birds which Arabella loved – there was an aviary here with 500 birds. Hertrich, in addition to overseeing the citrus and the grounds, also had to keep track of all the birds. A favorite of Arabella’s was the toucan and we have an original citrus crate label with a toucan, the only one we know that exists.

“We also found something interesting – the vast labor force that actually made this place come to be was not well represented. Although they didn’t necessarily go around taking pictures and keeping documents of their workers, we were able to find payroll records. We discovered that a third of the work force during the time were Mexicans from Mexico or Spanish, and they were paid significantly less than the European and American work force. It wasn’t surprising, but we’re starting to have scholars weed through and work with those documents that were heretofore unexamined.”

“And what would a show about Huntington be without talking about how much he was worth in 1919? He was worth $69 million that year and we have these preprinted ledgers and balance sheets, which he kept month by month, that showed his assets.”

“I will finish with a picture of Henry and Arabella – seen here as a young woman, not the woman we have come to think of as Arabella Huntington, the dowager wearing a widow’s veil,” pronounces Watts. “She was very much behind the scenes of this enterprise and was, in many ways, a huge force to be reckoned with. Her interests, as you may know, were in French decorative art and British portraiture, which he went on to collect later in time.

“When you exit the exhibition, you’ll see this great quote by Herman Hesse which we felt is emblematic of this project and of the year 1919: Every man is more than just himself; he also represents the unique, the very special and always significant and remarkable point at which the world’s phenomena intersect, only once in this way, and never again.”

Asked what he learned about Huntington that he didn’t know coming into this project, Glisson replies, “I haven’t been here that long so I didn’t know a great deal beforehand. In reading reminiscences about him and what people said, my takeaway is that he was someone who believed in trusting other people and he was very optimistic. He was always telling his staff to trust people to do the right thing. I thought that was very significant and interesting for a tremendously successful businessman and it suggests he must have found people he trusted and liked and then let them do their job. And that, to a large degree, is how you run a grand institution. In a sense, he clearly wasn’t that interested in being a book collector in 1905 or 1906 and then he got interested and focused on it. When it came to the grounds, his landscaper Hertrich suggested that they be systematic about it and create a scientific botanical garden like Harvard and he agreed right away. So there’s trust and this openness and a kind of capriciousness that, I think, shaped what we are today – an art museum, a botanical garden, and a library – which is a kind of unlikely combination.”

I inquire what they want people to get from the exhibition. Watt responds, “I always want people to leave with a sense of curiosity and wonder. For me, it was important that people understand the depth and wealth of our collection, that we’re an active research institution where scholars come in every day to study these materials, and that we have an active, vibrant collection which continues to grow.

Glisson says, “One, I hope that people, particularly those from L.A. and Southern California, come to the show and are surprised. Two, I hope they find something that they want to learn more about. And three, I hope they find something in the show that speaks to their own experience which, I think, is pretty likely because there’s all sorts of materials. Those are my hopes, and the biggest one is just for visitors to be very surprised.”

As for his favorite display among all the objects, Glisson reveals, “I love this red poster. Visually, this just jumps off the wall. It’s an incredibly powerful thing. And then there’s the text – Achtung! Stehenbleiben verboten! Auf Zusammenrottungen wird rucksichtslos geschossen – which translates to ‘Warning! Stopping is prohibited! Crowds of rioters will be indiscriminately shot.’ My German isn’t so good and I kept reading it and wondered about it. It turns out that this poster would have been printed during the German Revolution in January 1919, and it was posted on a government building with armed soldiers watching around it. Talk about this poster being a snap shot of history and how improbable that it got all the way from Berlin, maybe from the Reichstag, to Los Angeles.”

That Henry E. Huntington had chosen to establish the institution that would bear his name in the San Gabriel Valley in 1919, when he could have done so anywhere in the United States, was quite improbable as well. It might have been seen by some as a foolhardy decision at the time, but we want to think it proved to be a stroke of genius!