Also published on 13 November 2023 on Hey SoCal

Betye Saar, ‘Drifting Toward Twilight,’ 2023 (installation view) | Photo by Joshua White / JWPictures.com. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens

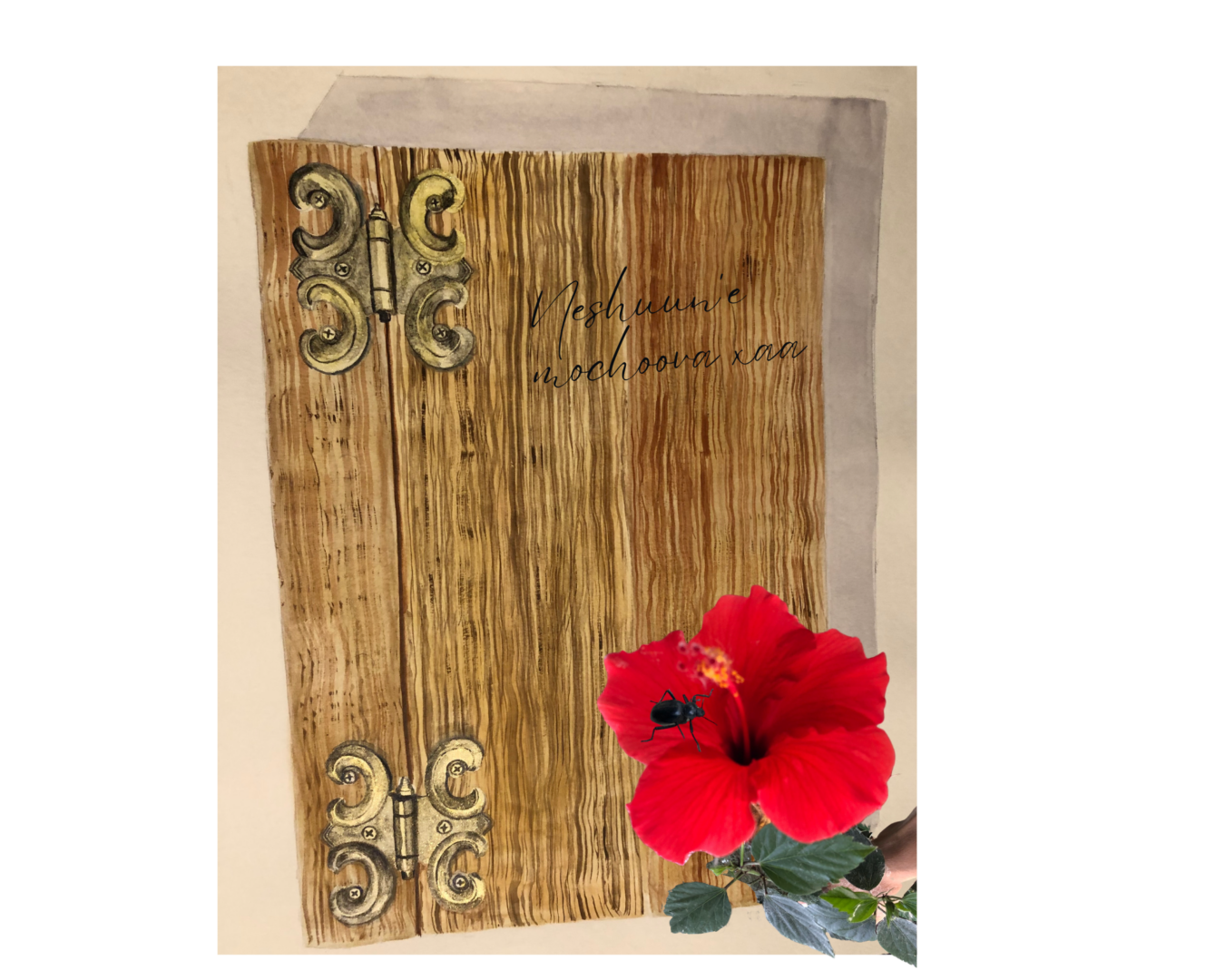

A newly commissioned, site-specific installation by renowned Pasadena artist Betye Saar opened to the public on Saturday, November 11, 2023 at The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens. Called ‘Drifting Toward Twilight’ it will be on view for two years at the Virginia Steele Scott Galleries of American Art, after which it will become part of the institution’s American art collection.

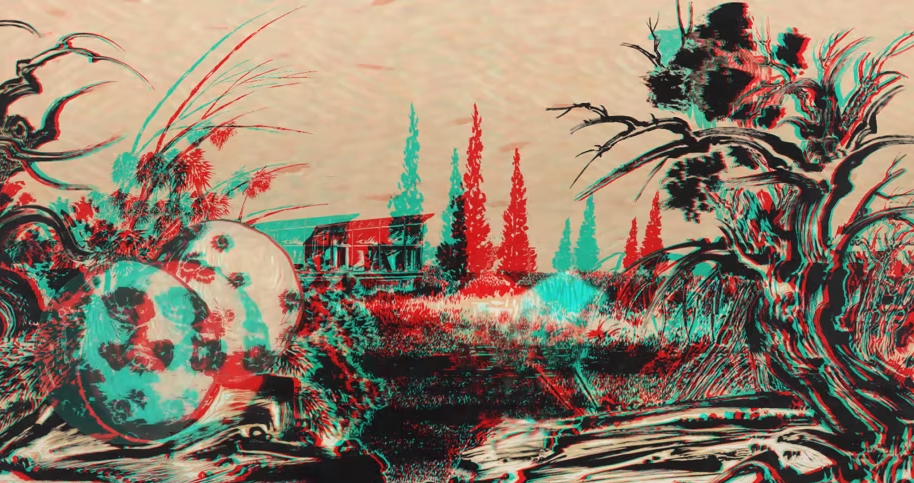

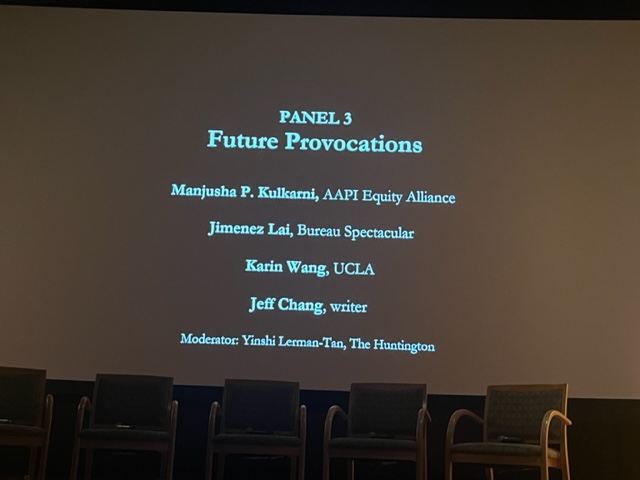

The large scale artwork – a 17-foot vintage wooden canoe and found objects, including antlers, birdcages, and natural materials Saar harvested from The Huntington’s 207-acre grounds – is the focus of an immersive exhibition ‘Betye Saar: Drifting Toward Twilight.’ It is co-curated by Yinshi Lerman-Tan, The Huntington’s Bradford and Christine Mishler Associate Curator of American Art, and Sóla Saar Agustsson, Saar’s granddaughter and the Huntington Art Museum’s special programs and digitization coordinator.

During the press preview on Friday, November 10, Dennis Carr, Virginia Steele Scott Chief Curator of American Art, remarks, “Betye Saar is one of the most important artists of our time. Her compelling voice has echoed in Los Angeles for many, many decades. But she grew up in Pasadena and has fond memories of walking in the Huntington’s gardens.”

Co-curators Lerman-Tan and Agustsson alternately talk about the installation. Lerman-Tan divulges that Saar specifically chose this location for the installation because it’s like a secret room. She explains, “It has a ‘cocoon-like environment.’ The walls are painted in an oceanic blue gradient, featuring a poem by Saar and phases of the moon. Shifting lighting effects in the gallery emulate phases of daylight to twilight, evening to night, and night to dawn. Inside the monumental canoe, Saar positions mysterious ‘passengers,’ including antlers in metal birdcages, children’s chairs, and architectural elements – all drawn from the artist’s ever-evolving collection of found objects. The space beneath the canoe will be illuminated by a cool neon glow, highlighting plant material foraged by the artist from The Huntington’s gardens.”

“Saar’s work evokes mysticism and the occult, as well as the human relationship to nature and the cosmos,” Lerman-Tan describes. “An immersive, watery space containing a canoe that is part vessel and part dreamscape, the installation gestures to the ancestral and mythological journeys, and the constant cycles of the natural world.”

Betye Saar with ‘Drifting Toward Twilight,’ 2023 (installation view) | Photo by Joshua White / JWPictures.com. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens

Besides her role as co-curator, Agustsson was instrumental in making this installation and exhibition a reality. Speaking by phone a week before the exhibition opening, she discloses, “I worked as an assistant to Christina Nielsen (Hannah and Russell Kully Director of the Art Museum) when I first came to The Huntington about two years ago. She happens to be a huge fan of Betye’s and wanted to do an exhibition with her. A few ideas floated around but I remembered that when I was working for Betye a few years ago, she had bought this vintage canoe and had started collecting antlers and natural materials for an assemblage. She’s done canoe installations in the past so this was a notion that has been marinating. I thought that The Huntington Gardens would be the perfect home for the canoe because the concept was to incorporate natural materials. Then Betye came up with the idea of foraging and using plant materials from the Huntington garden.”

Interviewed via email, Saar recounts her collaboration with the Huntington’s Art Museum and Botanical Gardens to realize this endeavor. “I visited the Huntington in the spring of 2022 and met with Christina Nielsen and my granddaughter Sóla Saar Agustsson and the idea of a project came up. Then some of the Huntington curators came to visit my studio and saw the canoe. I submitted a sketch and then made a scale model of the room and the canoe. It all just came together after that.”

“I have used canoes in some of my previous installations,” explains Saar. “To me it represents an element of indigenous people who used them, and the connection to nature. But I also really enjoy the shape of the canoe. The flow of it visually and how when you are in a canoe you feel like you are gliding. I acquired this particular canoe a few years ago and it was sitting in my garage waiting to become art. The Huntington commission made it take shape.”

In a short documentary film – produced for the exhibition and is being shown at an adjacent room – Saar explains her concept for the installation, “A canoe is an object of Early America as a means of transportation and I added the wood burrows to make it look vintage. There are three cages that make you think of slavery, of being taken care of and having certain things but you’re still caged – caged freedom in a way.”

The companion film also includes a footage of her foraging natural materials at the Huntington garden. Saar recollects, “I think it was back in April when I came to gather materials from the garden. There had been a series of storms and many of the trees had limbs break or had to be trimmed. I picked up what Mother Nature started.”

As she picks up discarded branches, she gets ideas about how to use them and asks an assistant to hand her her notebook. Saar expounds, “I am an assemblage artist and am inspired by the materials I find at flea markets and estate sales, or things people give me. Sometimes I’ll think ‘Oh this old red box needs to sit on a red table’ or something. But I also am inspired by things I see as I travel or images in my dreams and I’ll make a sketch of it. I always have a little sketchbook in my purse and a bigger art kit and sketchbook when I travel. Sometimes the sketch becomes an assemblage, sometimes it stays a sketch.”

Saar had a very clear idea about the ambience she wanted to produce and she kept close tabs on its progress. She relates, “I’ve been back and forth to The Huntington many times these past months. I was selecting the wall colors, choosing the lighting effects, etc. until it all came together to create the right mood. I wanted to feel immersed in the room.”

Agustsson says she worked very closely with Lerman-Tan to ensure they carried out what her grandmother envisioned. The inter-generational component of this exhibition will extend to the catalogue to be published in the summer of 2024. Agustsson will write a Q&A piece that covers Saar’s life and her career. It focuses specifically on her childhood growing up in Pasadena and her visits to The Huntington as a child and teenager, gardening practice, and an interview about the new canoe installation.

It will have a Director’s foreword by Christina Nielsen, followed by a short essay by Ishmael Scott Reed, an American poet, novelist, playwright, and longtime friend of Saar, as well as a re-publication of an archival interview he did with Saar in the 1970s. Lerman-Tan and Tiffany E. Barber, assistant professor of African American art at UCLA, will be contributing essays.

I ask Agustsson what it was like to work on a project with someone she knows so well, and she replies, “I’ve worked with her in the past for years so that helped me capture her vision and facilitate dialogue between her and the museum. I realize that this is a very special and personal project given her upbringing in Pasadena so I wanted to establish that particular connection.”

“For me, I found it to be really inspiring and meaningful especially getting to interview her and learning more about her,” Agustsson says further. “Even though I’ve grown up with her, there are things I continue to discover about her. I learned that she liked tap dancing when she was a teenager. I had no idea, I never heard that before! She’s 97, she’s had so many amazing experiences, and she’s done different kinds of art work in various media – costume design, designing greeting cards, printmaking, collage, immersive installations like this one, and she was a seamstress. It doesn’t surprise me that she also did tap dancing.”

Saar is the matriarch of a close-knit family of artists, as Agustsson’s account of her grandmother’s influence in her childhood years and present life as an adult attests to. “Betye has three daughters and six grandchildren. We were always drawing and doing art as youngsters. But even now, we have themed family parties and we’re all very supportive of each other. In a way Betye working in diverse mediums – assemblage, printmaking, collage, design, painting – was passed down. Two of her daughters, Alison and my mother Lezley, are artists and her other daughter Tracye is a writer and her studio manager. Alison does printmaking and sculpture, my mom does painting, collage, and assemblage.”

“I’m not really a visual artist but I do collages and dollhouses, which is like assemblage in a way. My cousin does printmaking and ceramics,” continues Agustsson. “My grandfather, Betye’s husband, Richard Saar was a ceramicist and my other cousin does set design, which relates to Betye being a costume designer. We like to go to flea markets together and are on the lookout to get each other certain things. My grandmother would also give me a lot of advice about art.”

Collecting found objects to create art is something Saar began doing since she was four or five years old. She says that whenever they moved to a new house, she would look through the previous owners’ trash to see what they threw away.

It’s no wonder then that assemblage spoke to her. Saar reminisces, “In the 1970s I saw the work of Joseph Cornell, right here at the Pasadena Art Museum in fact. I was inspired by how he took ordinary objects and made them into art. He made art that was beautiful and clever and had a sense of humor. It made me want to do that too.”

I inquire if there’s one artwork she created that means more to her than the rest, which one is the most memorable piece she made and why. Saar answers, “I don’t really have a favorite but I have a few works of art that I like because the viewer is invited to make an offering. Mti (1973) and Mojotech (1987). I like involving the public and getting them to experience my work in different ways. It’s also very interesting to see what people leave as an offering. Sometimes it’s a gum wrapper or money or ticket stubs. But sometimes people will leave a drawing they made on site or return later with a photograph or poem. I keep all of these items and feel they have a special power from people connecting to my work.”

That tangible takeaway is something Saar hopes for. She says, “As an artist, one tries to elicit an emotion from the viewer. This can be a tricky thing because I want people to feel what they feel but not dictate it. I hope that people come and see my exhibition in the gallery and then go out and find their own inspiration in the gardens. That’s what I did.”

When I ask Agustsson what she wants viewers to take away, she replies, “It’s meditative and I think she wanted to convey that emotion. It mimics floating in a body of water looking at the twilight and the moon; it has a very cosmic feeling. With all the turmoil going on in the world and in life, the room feels like a reprieve. I don’t get caught up in thinking about its meaning in terms of words. It’s refreshing to walk away with just an emotional response to it. And that’s very much integral in her process of creating – getting across an emotion – and intuition is a lot of what guides her.”

Agustsson adds, “I just hope that visitors and aspiring artists will relate to her method in harvesting and assembling the work where she demonstrates you can make art out of everyday objects and things you find on the ground. And that they get inspiration after seeing the film, watching her work in the creative process with so much enthusiasm at 97 years old.”

Finally, I ask Saar what it means for her to have her installation become part of The Huntington’s permanent collection and she says, “Well, being from Pasadena it means a great deal to me. I came to the gardens as a child and now here I am as an adult, a 97-year old, with my art in this amazing museum. It’s truly an honor that my work is now part of the legacy of The Huntington.”

‘Betye Saar: Drifting Toward Twilight’ represents a homecoming for Saar. Without a doubt, Pasadenans will be proud of her significance in this community and celebrate her iconic status in Black feminist and American art.

But the installation will profoundly affect all visitors. As they step inside the room, they will at once be enveloped in its warm embrace. And as they read Saar’s poem painted on the wall, ‘The moon keeps vigil as a lone canoe drifts in a sea of tranquility seeking serenity in the twilight,’ they will feel transported to a calm and peaceful place.